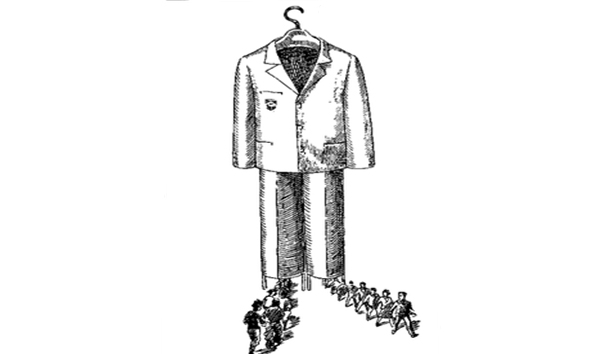

One of the most popular fads in public education is the reintroduction of school uniforms. In some American burgs, the proposal is greeted with general approval. In many, however, school boards, administrators, parents, and pupils are put through the usual paces of reform, going from unfounded optimism through a stage of unreasoning resistance, and finally to irreconcilable partisanship.

There is a problem, real or perceived, of declining attendance and worsening conduct in the schools. The problem is sometimes, by no means always, associated with an influx of this or that minority, because of immigration or desegregation or urban decline. Someone—an administrator or board member—comes back from a taxpayer-supported conference at Disney World with the bright idea—school uniforms, with or without a boot camp program for young black males in need of role models—and puts it before a board meeting. Community leaders of all ethnicities rise up to endorse the concept, citing all the successes in Milwaukee or some other place no one has been to, but before long the local chain newspaper outlet begins reporting on boys who do not want to cut their dreadlocks or pony tails and girls who regard dressing like a slut as an expression of their inner self (They are probably right.) Weak-faced parents come forward, whining on talk radio that children today are different from earlier generations of students—they cannot be ordered around. After all, they have rights. Or perhaps it is not school uniforms but an 11:00 P.M. curfew or an anti-drug program that authorizes routine locker searches or a mandatory program of community service that sends suburban teenagers, like so many Lady Bountifuls, into the benighted inner cities where they expect to find servile colored aunties who will hug them and call them “honey chile” for instructing them in the mores of the middle class.

At some point, someone will inevitably hire a lawyer, and before long the outside interests will send in their hired guns to stand up for the rights of people they have never met before, looking for the court case that will put them on the front page of the New York Times. You have seen it in your hometown, and if you have not, then you are wise enough not to read the generic chain newspaper that has bodysnatched the Des Moines Register or the Nashville Tennessean.

After spending nearly 50 years as student and parent, teacher, headmaster, consultant, and pundit, I have reached the not very momentous conclusion about education in America that schools, particularly public schools, are not places where learning takes place so much as arenas where children, their parents, and the agents of the state engage in a three-way battle of opposing rights. Here in Rockford, where we have had the usual posturing over school uniforms, the combat of rights is played out under the nose of the emperor, the federal magistrate who oversees the desegregation order he imposed on an unsegregated city. In the nearly ten years this battle has been going on, I have listened to charges of racism batted back and forth across the Rock River that divides the east side from the west, I have endured endless talk of equity in funding, I have heard about how the poor kids in west-side schools had to use old textbooks and sit at desks their parents used (as if old textbooks were not, in most cases, superior to their replacements and old desks a more palpable connection with tradition than any living museum), I have seen the endless list of tort fund expenditures to boost the morale of minority students and their parents (including weekend trips to expensive resorts), and I have watched an uneducated superintendent fighting an expensive turf battle with a barely literate “master” for the title of least articulate educationist this side of Chicago. But in all of the official discussion virtually no one has expressed any practical concern for what the students are actually learning apart from the annual ritual of covering up the significance of the test scores, which mean in plain English that no matter how they rig the tests or dumb them down, the gap between rich and poor, black and white stays the same. Not bad after spending only $166 million—over and above the districts regular expenditures—in nine years.

Every once in a while, it is true, a black parent goes on the radio to point out that the deseg remedy is doing nothing for his kids, but whenever he hears a non-black parent complaining about high property’ taxes, he will turn around and condemn him for racism and indifference. “You want to cut the taxes, but what are you going to do about educating kids who are victims of discrimination?”—as if it were everyman’s moral imperative to rear other man’s children. The one voice of sanity has come from an older black man who occasionally calls the Chris Bowman radio program to suggest that his neighbors ought to quit complaining about white indifference and clean up their yards and take care of their kids.

Who is, ultimately, responsible for the education of children? Depending upon whom you ask, you will receive one of two answers: the parents or the state. Homeschoolers and evangelicals typically give the former answer, while professional educationists—when they can afford to be candid—give the latter, and many of the school wars in this century have been carried out as a struggle of individual families banded together against a government that sees parents as an obstacle to the ultimate goal of education, which is to re-engineer Baptists and Lutherans and don’t-give-a-damns into model subjects of the American Democracy.

Statists are as alarmed by homeschooling as they once were by private and religious schools. Back in the 1920’s and 50’s, the disciples of John Dewey hardly took the trouble to disguise their plans to outlaw all forms of private education, openly declaring that no child should be allowed to escape the democratic formation imposed by government schooling. Although the case of Pierce v. Society of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary taught the educationists the valuable lesson of caution, many public school teachers (including those who put their children in private schools) openly oppose any form of vouchers or school choice on the grounds that they threaten the public school monopoly that is vital to democracy.

But it is not only government teachers and other statists who are suspicious of homeschooling. European Catholics have frequently remonstrated me for teaching my children at home. Children do not belong simply to the parents, they say, because some day those children will have to take their place in society. This view, which goes back through St. Thomas to Aristotle, is not a surrender to the state. On the contrary, it assumes a community rooted in shared experience and a common faith. Both in Europe and here in the United States, it was religious schools that most successfully opposed the state’s monopoly over the schooling of children.

The desperate straits in which we find ourselves today are largely the result of over a century of direct state action against the family, an invasion whose trail is marked by acts giving rights to married women, delinquency and child protection statutes, women’s suffrage, compulsory school attendance. Social Security, and no-fault divorce laws. At each step in the subjugation of the family, liberal politicians and journalists were able to identify a problem—loutish husbands who abused their authority, greasy immigrants who put their children to work instead of sending them to school, loveless marriages that created an unwholesome atmosphere for growing children—and these social problems served as a pretext for state intervention.

Unfortunately, husbands and wives, mothers and fathers have only been able to fight back with the enemy’s weapons, the Jacobinical rights of man, which all have poisoned handles, and we are confronted with the depressing spectacle of the men’s rights movement, organizations promoting fathers’ rights in radio spots paid for by the Ad Council, and universal declarations of parental rights that are an open invitation to U.N. intervention into domestic squabbles.

In the school wars, the bad logic of parents’ rights usually takes concrete form in proposals for vouchers or school choice. Of course, sensible parents who send their children to private schools will welcome the tax relief promised by vouchers, and no one in his right mind can fail to appreciate the opportunities which the various school choice plans offer to desperate families groaning under the oppressive weight of the public school monopoly. The underlying danger in any national scheme for school choice, however, was revealed some years ago by Charles Glenn in his analysis of European school-choice systems (Choice of Schools in Six Nations), and both Lew Rockwell and I have argued—”proved” would be a less modest word—that the net effect of vouchers would be the destruction of private and religious education and the complete empowerment of the national school bureaucracy.

There are metaphysical reasons why an educational philosophy based on a theory of parents’ rights cannot succeed, but there is also a practical reason, hi any contest with government, individual families can never win in the long run, since the state runs on energy that it sucks from the lives of families and communities. Homeschooling and little academies —and the choice plans that are expected to sustain them—may do some good, but we should never lose sight of the fact that they are desperate remedies. We are like frontier settlers whose last hope lay in the secret cellar where they could hide when the Indians had broken into the cabin. What the settlers needed was a stockade, a fortified community in which they could make a united stand against their remorseless attackers, and what parents need today are communities of friends and neighbors, church parishes and disciplined societies, within which they can defend their common interests.

Typically, it is religious communities—Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist—that have put up the most effective resistance, and while the average Catholic diocesan or Missouri Synod high school might not represent a grand improvement on public education in the suburbs, such schools do offer considerable protection to the families who cluster around them. For several years I sat on the board of a Lutheran school which, for all its faults, was a vivid manifestation of the Lutherans’ love for the children of their church community. I resigned my position when I realized that my own classical view of education was ultimately incompatible with the needs of a school whose highest goal was to teach children to be decent and hardworking citizens who would never know more than was good for them. I was foolish enough to think that more could be accomplished.

A few years earlier, I had served as headmaster of a private community school in the South Carolina Low Country. Most of what I know of politics and society I learned in my three years at the Archibald Rutledge Academy. Some men, I found out very quickly, are made for the work, but I am not one of them. It was not enough to design a curriculum, select books, hire and supervise teachers, and teach several classes every term. Even the business end of the job—raising funds, doing the taxes to save the expense of an accountant, helping to organize an annual “Shrimp Festival” at which the mothers raised tens of thousands of dollars—even that was secondary compared with the diplomatic responsibilities I had to discharge: mediating between board members and teachers, teachers and parents, in a village where everyone was related to each other to the degree of second cousin and where half the married couples I knew seemed to be double second cousins, and only I was a complete outsider.

Everything in a village is a national crisis—I use the word “national” advisedly, because it always seemed as if we were living in an independent city-state. The Episcopalians did not like the sermons they were getting from their supply priest (a sociology professor), and they went straight to the bishop to get him removed. A helpful legislator was going to pave the dirt road that led to the dirt road I lived on, and my neighbors and I backed down the state, the mayor, and the seafood docks who wanted a better road for their trucks.

The academy, which had been built by the fathers and supported by the heroic efforts of the mothers, was even more politicized than the churches or the town meetings. I designed the mildest of dress codes —no revealing sun dresses, no T-shirts with offensive slogans—and found myself awakened at the crack of dawn by a farmer whose wife had riled him up before breakfast. When I sent a boy home on Games Day for wearing a sweat shirt with “Divers Do It Deeper” emblazoned on his chest, his mama stormed into my office to tell me I had a dirty mind for reading something obscene into the slogan. This was no sheltered lady, by the way, but a two-fisted drinker who knew how to swear like a sailor.

I stirred up even more trouble by creating a special college preparatory program that required four years of Latin and a four-year history (not social studies) sequence: American, Ancient & Medieval, Modern European, British. One father insisted that his two slow children should be in college prep classes, but neither could apparently memorize the declension of puella. I persisted and succeeded in giving several country children a humane education beyond anything they would have received in the most fashionable schools in Charleston.

What I did not realize at the time, however, was that no matter what I did, I would remain an alien, an outsider, a potential threat to the community. One of my first acts was to expel a young hoodlum who was threatening the teachers, and a year later I expelled his older brother after he took a fake swing at my jaw. The kid was built like a gorilla and could have taken my head off. The next year, when he died in a car wreck, drowning face-down in a pool of shallow water, I refused to give the school a day off on the reasonable grounds that the dead young man was not a student. I did agree to let anyone who wanted go to the funeral, but this was not enough to squelch the gossip that I was persecuting the poor boy beyond the grave.

I was trying to set standards and maintain order, and I was not about to encourage sentimental adoration of a violent druggie. But the boy was everybody’s cousin or nephew; his poor mother was the sister of the landowner who had given the property where the school stood, and what I refused to understand was that right and wrong, good and bad, do not apply in quite the same way to your cousin’s son, no matter what he has done.

I left the next year over some trivial dispute, betrayed by the board members for whose children and grandchildren I had sacrificed several years that I might have spent writing or teaching, and it was only when I left the village that I became aware of how foolish I had been. All little communities are petty places, ruled by gossip and revenge, feuding and back-biting, and while an outsider will always be perplexed and disgruntled by these primitive loyalties, to the natives they are as natural and necessary as the wind and the rain.

Put another way, the village was a commonwealth, something like a Greek polls in miniature—albeit disintegrating—and the character of the polis was maintained by its peculiar methods of resolving disputes (its “constitution”) and its own customs of rearing and schooling children. If I had had 15 years and a good deal more wisdom than I possessed, I might have gradually made a contribution to the village traditions (supposing the village itself were not wiped out by a hurricane or by the invasion of displaced Yankee intellectuals looking for some new place to screw up).

But in rejecting the classical education that would once have been their own ideal, the people of the village were displaying an ability to close ranks against outsiders which is the first defense of a traditional community. Most Americans do not live in villages or even coherent neighborhoods, and it is the object of government today to prevent them from forming communities of resistance around their church or a small-town high school football team. Bigger is better, according to the experts, and consolidated schools afford students more individual choices, more opportunities to become different from their parents. And if consolidated school systems become so oppressive that even the supine American taxpayers get restive, then the experts have to devise scheme after scheme to fix the little problems without ever touching the central question: Why do we have to have consolidated school systems that operate under the dual authority of state superintendents and the U.S. Department of Education?

Only a hundred years ago, most public schools were really community schools under the direct control of the parents and relatives who paid the taxes, elected a board from among themselves, and meddled in school affairs with impunity. The simple test of any school reform plan is to ask in which direction it goes—toward or away from the community school. In the case of most voucher plans, the answer is plain: power is flowing to the state capitol and to Washington. With other plans, like charter schools, the answer is not so simple. In some cases, a charter school is simply an educationist’s gimmick—an all-computer school, a fine arts school, even a hotel-management high school. These specialized academies divide neighborhoods and contribute to the social fragmentation that leaves us helpless.

But it may also be possible for groups of parents to establish schools that reflect the character of their neighborhood and their ethnic and religious traditions. In time, such little experiments might serve as centers of the community and pockets of resistance against the homogenization being pushed by Republican bureaucrats like Checker Finn and the promoters of the National History Standards.

Most conservatives have learned, now that it is almost too late, that the individual cannot take his stand alone and unaided against the powerful national and international interests that are devouring human communities. What social conservatives have failed to learn is that families are almost as fragile as individuals, especially now that rights legislation has driven wedge after wedge into the chinks between the sexes and the generations. No help can be expected from national governments or from any international agency or movement that wants to save the children or preserve the family—internationalization is the last stage of the disease, not its cure.

It is only by living in communities that we can rear our children in security, and it is only by working locally that we can protect our communities and the schools—public and private—that represent them. Ten thousand battles must be fought over school board elections, bond issue referenda, and local “choice” initiatives, but no single family—or even a list of families on a petition —can win any of them. Only a community can close ranks against the federal judges, experts, and legislators who are taking away our children.

The battle lines cannot be drawn in defense of parental rights. Such tactics serve only to create one more whining minority group dependent upon government (world government, if some have their way). Our ancestors took on an entire continent, village by village and parish by parish, and that is exactly how we shall have to take it back.

Leave a Reply