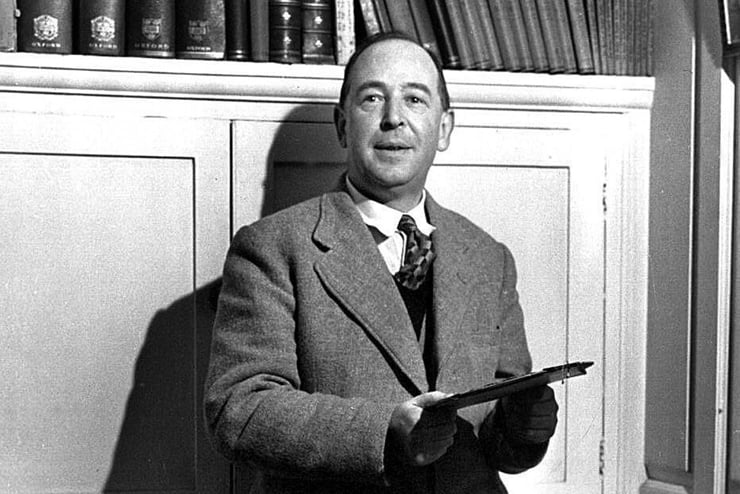

The cover of your November issue suggests the truth that we, conservatives and especially conservative Christians, are engaged in spiritual warfare. And yet, smack in the middle of that issue, you print an article, “Remembering C. S. Lewis.” The reader is led to believe that this man has been a powerful instrument of truth and has fought the good fight of faith to the very end.

In Lewis’s Surprised by Joy (1955), we discover that he defended pederasty and perversion as “the only chink left through which something spontaneous and uncalculating could creep in”…. Then, we come to the more sordid aspects of his life. He had a relationship with a schoolmate, Arthur Greeves, and throughout his life wrote more letters to him than any other person… Later biographies disclosed that Mr. Greeves was a homosexual. It appears that Lewis was never moved by the impulse to separate as is mandated by both the old and new covenants.

Instead of contending for the faith, it appears that Lewis was, plausibly, another swamp creature, beguiled by his own clever wit and talent, and eager to lead others into the broad path of destruction. Why does a magazine that is dedicated to exposing the unfruitful works of darkness puff up a man who has the appearance of orthodoxy but who has chinks in his armor that point to the liberal left?

—Erik Thorp

Warwick, R.I.

No True Conservative

Prof. Gottfried, I’m a fairly new subscriber to Chronicles and have read with interest your special edition collection of “Remembering the Right” articles. It has been of interest to me that so many of the featured writers started out on the far left, even with Marxist leanings. Being new to delving deep into political philosophy, I’m stuck by the fact that many of these thinkers, in an incoherent way, stray far fom my nascent understanding of conservatism—personal liberty, small government, fiscal prudence, and patriotic reverence for the founding documents. So, I hope that you will respond to a few questions from an enquiring mind.

In simple terms, what separates Chronicles conservatism from the neoconservatives, in your mind? Also, I’ve been confused by more than one of these writers who seem to have a problem with Lincoln—what’s that all about?

Finally, there’s an old saying that conservative youth have no heart, but that progressive adults have no sense. As I read “Remembering the Right,” I had trouble seeing a sensible transition for more than one of these individuals, or whether it ever completely occurred. Can you enlighten me there?

—Leon Borchers

Atlanta, Ga.

A General Reply to Some Recent Letters and a Reflection on the Legacy of Abraham Lincoln, From the Editors

We have been noticing lately a spate of letters from a small handful of angry readers who demand that Chronicles cease publishing articles that challenge their political or religious world views. Despite often threatening to unsubscribe, some of these correspondents write month after month, seemingly unwilling to follow through with their threats.

The complaints of this group are varied, and often their letters are too long-winded to publish in full in this section. Some recent examples that we’ve published in this “Polemics & Exchanges” section include the letter in this issue, which objects to our profile of (the apparently morally retrograde) C. S. Lewis. Another was upset with our critique of a well-known popular historian “On Victor Davis Hanson” (January 2021 Chronicles). Our perturbed correspondents also include a handful of piqued Poles who are hypersensitive to any mention in the magazine of Polish history, and who took umbrage in lengthy, unpublished letters at matters too minute to be of interest to a general readership.

Other letter writers have more substantial objections to disagreements with one or another Chronicles writer’s definition of true versus false conservatism, or the true versus the false ideals of the Founding Fathers, or—perhaps especially—of matters relating to the Civil War (or the War of Northern Aggression, if you like).

Even as we have received these letters of outrage, our list of subscribers continues to grow. We think these things are not unrelated. Unlike many bland magazines that are the products of establishment conservatism, Chronicles continues to be a provocative outsider voice that challenges the establishment orthodoxy, and which allows debate within its pages.

Our commitment to publishing a selection of interesting reader letters every month, even (or especially) angry or critical ones, sets Chronicles apart. What distinguishes us from the “cancel culture” in either its standard leftist or Conservative Inc. form, is that we take our commitment to a free exchange of ideas seriously.

This does not, of course, mean that Chronicles is not committed to traditional conservative tenets, because it most certainly is. The magazine’s publishers and editors believe in traditional families with assigned gender roles, the eternal validity of biblical morality, the unmitigated evil of the modern administrative state, and the perversity of egalitarian politics. We also believe the conservative establishment in the United States has done pitifully little to hold back the advance of the left for several decades, and that its only major accomplishment has been to disable everything to its right.

Chronicles also has a record of being quite open to views that the conservative movement does not want to talk about, for example, the right of Southern states to secede from the Union in 1861 without having their section decimated by invading Northern armies, the unfortunate consequences of Reconstruction, and the international disaster of American military intervention in the Great War or in the Kosovo fiasco (which resulted in the wholesale expulsion of Serbian Christians from that region).

Although we do take positions for which the left may hate us, we are also keen on open debates, and have often featured articles that express different views from those held by our staff.

The second letter writer in this number is surprised that our contributors have dared to criticize Abraham Lincoln, and, to his bemusement, we don’t address the problem of unbalanced budgets and other matters that are standard Republican Party talking points.

But we are not part of the GOP or of the standard “movement” conservatism. There are lots of magazines, websites, and cable news programs that are covering those topics that our reader thinks we should engage. Why must we duplicate what others are already doing?

Furthermore, why are we not permitted to raise questions about the rhetoric or war policies of Abraham Lincoln? Is our 16th president a divinity who stands above critical judgment? In his life Lincoln was a controversial figure, and we see no reason he should be treated differently in historical perspective.

We repeatedly hear the same bizarre historical interpretation about Lincoln’s moral mission from Conservative Inc. and with vehemence from Mark Levin and Glenn Beck. These media celebrities insist that slavery was our collective original sin as a country, which Abraham Lincoln helped us expiate in a purgative ritual that cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

This was apparently well worth the price since we have now been shriven (at least on Fox News) of our shared guilt. The tens of millions of advocates of reparations for American blacks would naturally differ on whether we’ve been absolved. If our sins were as wicked as both the leftist media and the establishment conservative media would lead us to believe, these special pleaders may have a point.

Some historical perspective may be helpful here. When the United States came into being in the late 18th century, slavery existed in much of the world, including in the British and French empires, and perhaps most brutally in Africa, from whence most of American slaves came. If slavery were a collective sin, it existed everywhere since the dawn of humanity as a desirable form of labor. The American South did not produce a slave system of unsurpassed brutality, but one that allowed the slave population to multiply at an unsurpassed rate for servile labor. We may point this out even when speaking about an institution that we are well rid of.

We’ve never bought the argument that slavery was especially wicked on these shores because of the passage in the Declaration about all men being equal. The French proclaimed their Declaration of the Rights of Men and of Citizens in August 1789 but still maintained a vast slave population in the West Indies. Robert Paquette, a leading historian of slavery in the western hemisphere, raises the rhetorical question: Does anyone think that a slave in 19th-century Virginia would have preferred being relocated to a sugar plantation in Cuba or Brazil, or to becoming a serf in Russia or China? Unlikely.

Paquette also finds it remarkable that the data he learned as a university student from a Jewish Marxist professor, Robert Fogel, about the relatively benign condition of slaves in the American South (relative to other places where slavery was practiced) can no longer be discussed even in supposedly conservative journals.

If there were a conflict between the notion of universal individual rights and human bondage for non-citizens, this was not as obvious to most people in the 18th century as it would be to a more passionately egalitarian posterity. Although opponents of slavery could be found at the time of America’s founding, at most these opponents with very few exceptions favored manumitting slaves without granting them full rights of citizenship, which, as far as we can tell, was the position of the author of the Declaration.

Jefferson wanted slaves gradually freed and colonized outside the United States. Although Lincoln changed course during the Civil War, he too long favored the settlement of manumitted slaves in Haiti or Central America. One could accuse these critics of slavery of not being as sufficiently committed to egalitarian principles as they should have been, or as committed as Glenn Beck, Mark Levin, or perhaps Kamala Harris would have wanted them to be.

There is also no evidence that most of those who died in the American Civil War gave their lives specifically to rid this country of slavery. Lincoln grasped Northern sentiment properly and for that reason fought a war motivated primarily to save the republic. In his famous letter to New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley on Aug. 22, 1862, and in his second annual address to Congress, Lincoln made clear that he was prosecuting war against Southern secessionists to keep the Union together.

Lincoln’s “paramount object in this struggle,” as he told Greeley, “is to save the Union.” He was first and foremost a nationalist, not an abolitionist. It is also inconceivable that slavery would not have disappeared even without the bloodbath that Lincoln’s invasion of the Southern states brought about. Slavery disappeared elsewhere without the catastrophe that befell the United States in the 1860s.

Allowing for local variations, Lincoln, the nationalist and consolidator, was a child of the mid-19th century, like the unifiers of Italy and Germany, Camillo Cavour and Otto von Bismarck. All these figures fought against regionalists wedded to agrarian, and partly seignorial economies, and they established centralized nation states, or states that were more centralized than those that preceded them. Lincoln has been the most honored of the three, but his state-building was by far the most destructive of human life, and his legacy perhaps the most dangerous in its ultimate consequences.

Unlike other nationalists of the 19th century, as Willmoore Kendall correctly pointed out, Lincoln urged his country to spread the ideal of equality, “the proposition” to which America had committed itself in becoming a nation. This ideal was assigned universal significance, and Kendall correctly observed that it provided a moral basis for perpetual crusades on behalf of a mischievous abstraction.

If, as Conservative Inc. now insists, Lincoln’s idea that a “proposition” has made America an “exceptional nation” unique in human history, we would rather find some other reason to be exceptional or unique. For example, by especially exemplifying ordered liberty in a particular time and place, or by being uniquely successful in allowing citizens to prosper in a lawful society.

We do not write this to demonize Lincoln, who was an extraordinary historical figure and one of the most impressive orators in the English language. Also, like historian and philosopher Richard Weaver, we are impressed by the argument from principle that Lincoln makes in his debates with Stephen Douglas in their race for the U.S. Senate in 1858.

Unlike Douglas, Lincoln emphatically challenged whether a deep moral question, which is what he considered the extension of slavery into the territories, could or should be settled by majority votes. Of course, back then there were real majority votes, unlike the current imitation of an electoral system, in which the media and their friends in the Deep State shape the outcomes.

But Lincoln was also a problematic hero, who was fully complicit in initiating a bloody, fratricidal war and seeing it through to its brutal end. Among the long-range consequences of the Civil War was the permanent damage done to the dual sovereignty with which the American republic was established, with shared, inalienable powers assigned to both the federal and state governments. Lincoln further launched the never-to-be fulfilled mission of bringing equality first to American citizens and then to the rest of the world. We are still living with the consequences of that dubious achievement.

We do not intend to do what Lord Acton urged us to do when he encouraged historians to “play hanging judge over the past.” The students of the past should generally avoid indulging that obnoxious habit. But it would be unfair to Lincoln’s legacy if we did not mention the political implications of what he said and did. And since he is today honored precisely as an upholder of a universal value that it behooves Americans to bestow on humankind, it would be remiss of us to look at his statesmanship without noting that fact.

It may be less noteworthy that Lincoln (along with the very leftist children’s book author Dr. Seuss) is now being “canceled” by those on the left than the fact that he appealed to the very idea of radical equality that the left glorifies. And, that Lincoln asserted the primacy of that value in the context of a national mission to be vindicated through war.

It is also futile to make academic distinctions between Lincoln’s armed pursuit of equality and the more extreme forms that ideal has taken 150 years later. As a Genevan critic of the French Revolution warned as the Jacobins were taking power in France : “Like Saturn, revolutions devour their children.”

As we on the right work desperately to quell the egalitarian passions that are destroying constitutional government in this country and elsewhere in the West, it would be proper to pose the question of whether Lincoln should have been turned into a living god by the conservative establishment. There are other candidates for national honor (but not the divinization bestowed on Lincoln) whom we would gladly put before him, starting with George Washington.

A second problem with the current Lincoln-worship was stated by the political-legal thinker Bruce Frohnen in the once-illustrious but now discontinued online magazine, Nomocracy in Politics. Frohnen offered this critical observation while discussing Basic Symbols of the American Political Tradition (1971) a study published by George Carey after the death of Willmoore Kendall, with whom Carey collaborated in producing this work. Frohnen expresses the deep reservations of Carey and Kendall regarding the cult of Lincoln when he wrote:

The problem with Lincoln, for Kendall and Carey, is that he dedicated the United States to a principle. And dedication to any principle would be a problem for the American way. Certainly a case can be made for a certain definition of equality as a good thing. But any principle is a dangerous thing for any tradition to take as its common, collective goal. Traditions, societies, peoples, are not dedicated to principles. Ideologies are dedicated to principles. And ideologies are the motive force for armies and for campaigns to punish heretics and enforce a uniformity of life that spells death for human variety and living tradition.

It would be hard for us to improve on that criticism.

Image Credit:

above: C. S. Lewis [image in the Public Domain]

Leave a Reply