The topic of slavery and reparations has been much in the news of late and might feature prominently in next year’s presidential elections. Slave ownership taints the reputations of historical figures, to the point of provoking campaigns against their commemoration. Modern dismay over slavery is quite justified, but a couple of reality checks might be in order.

To cite a specific example of a prominent slaveholder, take Jonathan Edwards, one of the greatest religious and literary figures in early American history. In 1731 he traveled to Newport, R.I., to buy a “Negro girl named Venus,” and at various times might have owned as many as six slaves. To take another religious superstar of the era, what about evangelical George Whitefield? His campaigning led in 1751 to the legalization of slavery in the colony of Georgia, in which it had hitherto been forbidden. How could these figures have been—in our eyes—such moral monsters? How dare we commemorate them?

But the question then arises of how they should have known differently. In the English-speaking world, slavery was viewed as morally permissible until about the year 1770, which marks a decisive upsurge in anti-slavery sentiment and agitation. Only after that watershed moment did slavery become much more self-evidently wrong, sinful, and reprehensible. Very gradually, the Anglophone attitude against slavery spread throughout civilized Europe and beyond.

Prior to 1770, plenty of British and American religious and humanitarian thinkers preached that slaveholders should treat their human property with decency, mildness, and consideration, and to free them on easy terms when appropriate. But outright opposition to slavery was extremely rare and sporadic. We might reasonably ask how or why, at that particular time and place, someone like Edwards could have been expected to go against that social current. And that should surely affect how we judge a person’s character and fitness for historical commemoration.

One may protest that a white European Christian civilization that allowed slavery was by its nature so thoroughly tainted that it represented a kind of cancer on the earth, which needs to be purged from history. But we would then need to ask what point of reference we are using to condemn that culture, and whom we might celebrate in its place. Historically, where do we find cultures that rejected and condemned slavery as an institution, and which posed stern moral objections to the fact of slavery? Such did exist, notably in much of Christian medieval Europe. But where else? Not, of course, in the Classical world; nor in the world of Islam until very modern times; nor in many modern African communities; nor in Persian or Indian or Chinese history; nor among Native Americans, Aztecs, or Mayans. Not only were these slave societies, but the slavery principle remained uncontested.

We have to read carefully here. Because of our modern attitudes, we happily cite early references critical of slavery or slaveholding, and these are not too difficult to find. In the early Christian world, venerated Fathers urged masters to treat their slaves well, avoiding brutality or sexual exploitation. Those masters should also free slaves on generous terms when possible, and humanitarian advocates condemned the savagery of the slave trade. Early Christians were urged to follow the Old Testament laws of slavery, which prescribed strict time limits on the practice. In Islam, the Prophet Muhammad frequently praised the virtue of liberating slaves, an act that gave special pleasure to Allah. But like his Christian predecessors, Muhammad was urging a decent and humane implementation of the slavery system, and assuredly not its abolition.

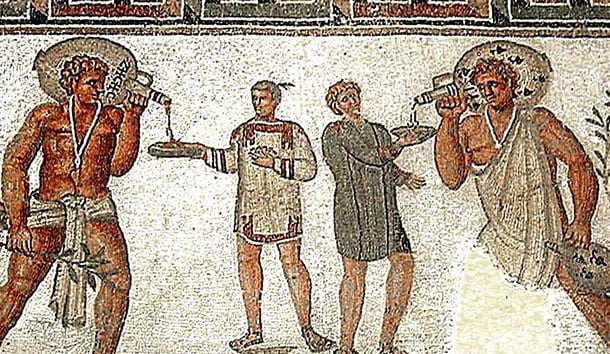

In the Classical world, anyone who could afford to own slaves did so without qualms. That included the holders of vast landed estates, but also quite small-time people whom we might think of as lower-middle class. The overwhelming majority of those who left writings that survive into later times were of the social class that owned slaves, even if we cannot point to individuals and definitely assert that they did so. That majority includes, among other people, most of the prominent Christians that we know of before around the sixth century, and most of the early Church Fathers. If we can’t clearly show that a particular individual in that era did not own slaves, then we should assume that they did, and that they did so without the slightest moral qualms. And as I say, the same applies to any literary or historical figure we might know from India, China, Africa, the Islamic world, or Native America.

So if the fact of slavery means that we have to condemn a whole culture, and remove its works from our canon, what are we left with? Egypt and Greece, goodbye—and goodbye Rome! And arguably, goodbye to anyone and everyone from our entire, noxiously tainted, global past.

Leave a Reply