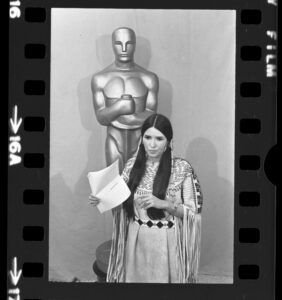

Back in 1973, when more than 40 million Americans still watched the Academy Awards, an actress who called herself Sacheen Littlefeather took the stage as a proxy for Marlon Brando, who was boycotting the proceedings despite being the prohibitive favorite to win Best Actor for his role as Vito Corleone in The Godfather. Brando was protesting what he said was Hollywood’s mistreatment of American Indians. Dressed in beaded doeskin, her long dark hair secured by colorful woven ties, and her fingers and wrists adorned by turquoise jewelry, Littlefeather described the suffering of the American Indians. “I spoke my heart, not for me, myself, as an Indian woman but for we and us, for all Indian people.”

The Academy didn’t question Littlefeather’s Indian identity, although the things she later said should have aroused at least some curiosity, if not suspicion, about her tribal credentials. She said she was a White Mountain Apache and had grown up in a shack. To explain why she didn’t look particularly Indian, she said her mother was white. She first described her father as an Apache but later as half Apache and half Yaqui, and all alcoholic. She said that she and her mother were regularly abused by him.

After her appearance on behalf of Brando, Littlefeather got roles playing an Indian in several of the worst movies ever made, The Trial of Billy Jack, Johnny Firecloud, Winterhawk, and Shoot the Sun Down. Without acting chops or great beauty, her minor roles ended in 1978. She blamed it on being “red-listed” by the Academy, but except for a couple of uncredited bit parts, her movie roles all came after her 1973 Awards appearance. For 50 years afterward, she kept repeating her false story until in June 2022 the Academy issued a formal apology for the suffering they had supposedly caused her.

Littlefeather’s limited acting career did allow her to establish herself as a professional Indian, being interviewed by the media about every Indian-issue-du jour. Although she often said things that were demonstrably untrue, she was never challenged—only patronized. For instance, she said she was one of those Indian activists who had occupied Alcatraz Island in the late 1960s. Those Indians who were there, however, said that her appearance at the Academy Awards was the first they had ever seen of her. My favorite Sacheen whopper is one she told about John Wayne. Straight-faced, she said Duke attempted to attack her at the Awards ceremony and that it took six security guards to restrain him.

When Sacheen Littlefeather died early in October 2022, The New York Times described her as an “Apache activist and actress” whose father came from “the White Mountain Apache and Yaqui tribes in Arizona.” Other newspaper obits described her similarly. Only days later, though, Littlefeather was revealed as a fraud—by her own sisters, Trudy and Rosalind. They said their sister, who real name was Marie, was born in Salinas to a father from Oxnard. His family had come to California from Mexico and had no connection to any Indian tribe. They had been listed as white in every census. The mother was Geroldine Barnitz of French, German, and Dutch descent. They lived in their own middle-class home in Salinas, and their maternal grandparents lived next door. Their father was not an alcoholic, and he abused no one.

They said Marie became interested in modeling and acting when she was a student at San Jose State University and later in San Francisco. With all things Indian becoming a fad in the counterculture of the late 1960s, Marie Louise Cruz was soon marketing herself as Sacheen Littlefeather. When Playboy issued a call for Indian models, she responded immediately. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen recounted the incident: “Sacheen Littlefeather, the Bay Area Indian Princess, and nine other tribal beauties are sore at Hugh Hefner. Playboy ordered pictures of them, riding horseback nude … and then Hefner rejected the shots as ‘not erotic enough.’”

Trudy said Marie didn’t like herself and “created a fantasy. She lived in a fantasy, and she died in a fantasy.”

Long before Sacheen Littlefeather arrived in Hollywood, there was Iron Eyes Cody, everyone’s favorite Indian actor. Saying he was Cherokee and Cree, he began appearing in movies in the 1920s as an Indian extra. In 1930, he was in the first movie starring John Wayne, The Big Trail. Cody’s character had no name, and he was uncredited. In 1931, in Fighting Caravans, starring Gary Cooper, Cody’s character got a name, “Indian After Firewater,” but still no screen credit. Cody appeared uncredited in another three movies until his role in 1932 as Little Eagle in Texas Pioneers got him a screen credit as Iron Eyes. It wouldn’t be until 20 movies and four years later, in Custer’s Last Stand, that he would get his second screen credit, again as Iron Eyes.

Two dozen movies later, in 1939, he got screen credit in Overland Mail with the name he would be known as for the rest of his life, Iron Eyes Cody. Whether earning screen credit or not, Cody was easily the most recognizable Indian actor in Hollywood. In 1942 alone, he appeared in an astounding 18 movies. In 1948, in a great spoof, The Paleface, starring Bob Hope and Jane Russell, Cody’s character is Chief Iron Eyes. Several movies later, Cody again played Chief Iron Eyes, but this time as a Canadian Indian in Mrs. Mike.

Cody continued working in movies during the 1950s—he portrays Crazy Horse in 1954’s Sitting Bull—but like many other Western movie actors of the 1930s and 40s, he found regular and lucrative work in the new medium of television. There was hardly a Western-themed series in which Cody didn’t make an appearance or two, including The Cisco Kid, Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, Cheyenne, Sugarfoot, Maverick, Lawman, The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin, Death Valley Days, Gunsmoke, Rawhide, the list goes on.

I recall watching Iron Eyes Cody frequently on The Tim McCoy Show, which aired locally in Los Angeles in the early 1950s. McCoy, who had actually been a real cowboy as well as a cowboy actor, had Iron Eyes Cody on the show as a regular guest. We kids thought that Iron Eyes was not only an Indian but a chief, and that acting was something he did on the side.

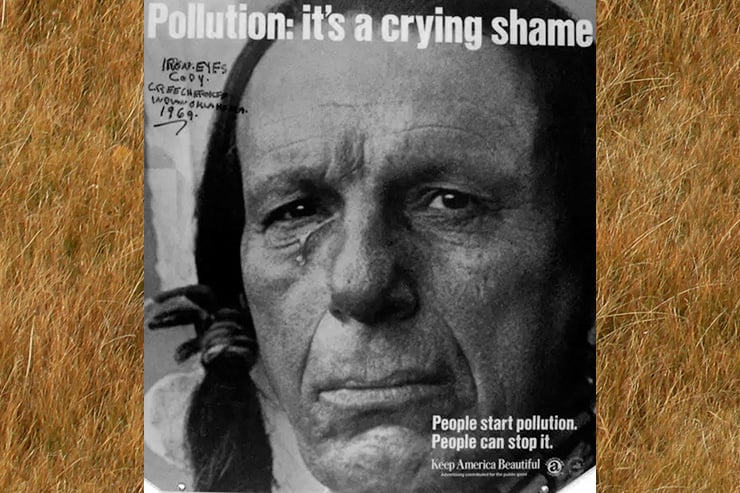

It was ironic that after more than 40 years of movie and television work, Iron Eyes Cody became best known, especially by younger generations, as the “Crying Indian” for his work in a public service announcement sponsored by the Keep America Beautiful organization. First aired on Earth Day, 1971, the PSA has Iron Eyes paddling a canoe through water that at first is clear and pristine but later becomes polluted. He pulls ashore in a littered environment just in time to have a paper bag hurled from a passing car land at his feet and burst open. Fast-food wrappers cover the ground and his moccasins. The camera pulls tight on Cody’s face as a single tear slowly rolls down his cheek.

The PSA was enormously popular, and soon there were hundreds of thousands of posters featuring the close-up of Iron Eyes crying. The posters became iconic on college campuses.

When Iron Eyes Cody died in 1999, the Los Angeles Times and every other major newspaper described him as a Cherokee and Cree actor who grew up on a farm in Indian Territory.

Iron Eyes was actually born Espera Oscar de Corti in Vermillion Parish in southwestern Louisiana in 1904 to a Southern Italian father and a Sicilian mother. He and his two older brothers arrived in Hollywood in 1924 and found work as extras, using the surname Cody. The brothers soon tired of Hollywood, but Oscar Cody stuck around and found that with his dark complexion and prominent nose he could pass for an Indian, which got him regular work. He was soon claiming his father was a full-blood Cherokee and his mother a full-blood Cree. Over the years, he added layers to the story, including being reared on the farm. He convinced everyone—and maybe even himself—that he was Iron Eyes Cody.

Actors reinventing themselves has been part of Hollywood since the earliest days of the industry. Sacheen Littlefeather and Iron Eyes Cody were part of a long tradition, which seems generally harmless in an industry that is, after all, about dress-up and make-believe. But what about the latest fake Indian of note, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren? For two decades, Warren tried to game the system in academe by claiming to be a Cherokee. She initially denied having done this, but then Warren’s 1986 registration card for the State Bar of Texas surfaced, and under “race,” she had written “American Indian.”

There is also the 1984 cookbook of so-called American Indian recipes, Pow Wow Chow, which includes five recipes from Warren, self-identified as a Cherokee. The recipes were all found published elsewhere, long before Pow Wow Chow, and had nothing to do with tribal cuisine. Two were from a famous French chef of the 1960s and 70s, and one was from a 1959 article in Better Homes and Gardens.

Warren also listed herself as an American Indian when she taught at the University of Pennsylvania and at Harvard University. Harvard listed Warren as an American Indian in its federal affirmative action forms from 1995 to 2004 and touted her “woman of color” status as a faculty member. Warren also listed herself as non-white in the Association of American Law Schools Directory of Faculty.

She probably would have remained an American Indian, were it not for her political ambitions. Exposed as a fraud, she thought a DNA test might save the day by finding a fragment of American Indian genetic matter. She seemed to fear the worse, though, and instead of having an established outfit such as 23andMe conduct the test, she had her own private “expert” analyze her DNA. Predictably, the hired gun said she could possibly be part American Indian, a whopping 1/1024th. Warren initially acted as though the alleged finding was a victory, but it quickly became apparent that making a racial claim based on less than one one-thousandth of your DNA struck everyone as absurd. Another fake Indian bit the dust.

Leave a Reply