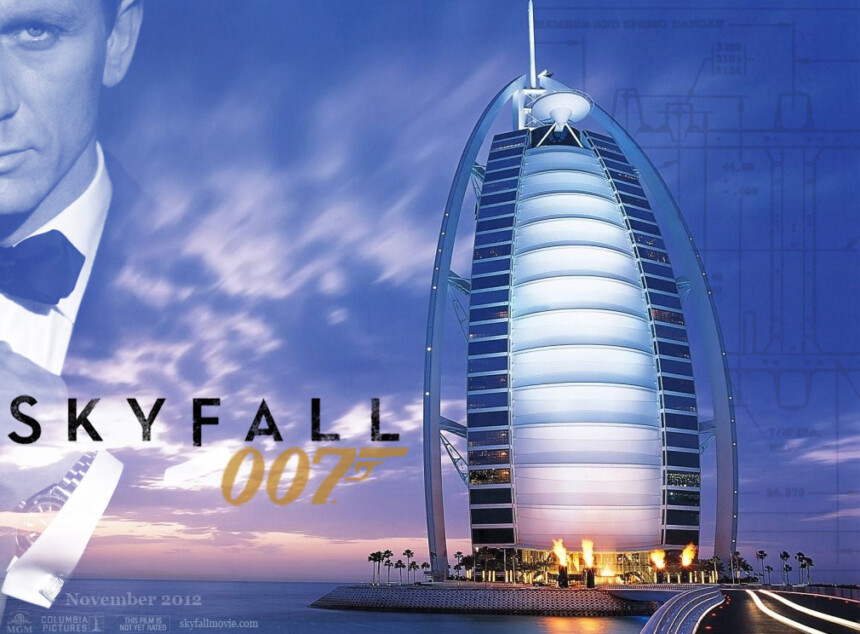

Skyfall

Produced by Metro-Goldwyn Mayer and Eon Productions

Directed by Sam Mendes

Written by Neal Purvis, Robert Wade, and John Logan

Distributed by Columbia Pictures

Lincoln

Produced by 20th Century Fox and Dreamworks Pictures

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Written by Tony Kushner

Distributed by Touchstone Pictures

No less an authority than Vatican City’s daily newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, has declared James Bond a Roman Catholic. For evidence they cite his latest adventure, Skyfall, in which Bond proudly proclaims his hobby to be resurrection. Want more? At a critical moment, Bond escapes his foes through a priest hole in his family’s ancestral seat on the Scottish moors. A priest hole, as fully three percent of the Bond audience knows, was a hidden tunnel in the homes of recusant Catholics in the 16th and 17th centuries. They were developed shortly after England took a wrong theological turn under the vindictively capricious monarchy of Henry VIII, who decided that Rome was no longer worthy of his subjects’ loyalty. Those discovered practicing the old religion were liable to be tortured and beheaded. The priest hole was designed so that a cleric calling on a recusant home to say Mass could escape without notice, should Protestant officials stage an impromptu visit.

Well, this was enough for L’Osservatore, and what’s good enough for them is good enough for me, as long as we don’t get canonical about it. Bond doesn’t exactly exemplify the Church’s four cardinal and three theological virtues. In fact, he rather flouts the virtue of temperance, smoking and drinking more than is good for a self-regarding secret agent, not to mention prudence, driving well above the speed limit on both four and two wheels. As for the theological virtues, L’Osservatore is mum.

I do not know how seriously Bond’s new director, Sam Mendes, takes these theological themes, but he does seem virtuously committed to continuing the no-nonsense regimen begun in Casino Royale. Gone are the adolescent double entendres (Pussy Galore’s been silenced), and Bond no longer winks at the audience as Sean Connery did through the windscreen of his Aston Martin. Instead, we get dour Daniel Craig of battered visage and knotted musculature, a dead-serious Bond. Unlike his predecessors, he doesn’t hesitate to walk out on a willing beauty when duty calls. And his Bond bleeds and even vomits on occasion. Casino’s director, Martin Campbell, went so far as to begin his film in black and white to signal just how serious Bond had become. While the movie’s palette soon bloomed resplendently, Craig’s performance remained formidably black and white.

Unfortunately, Mendes hasn’t Campbell’s wit. He prefers cliché. He’s allowed his writers to get away with dialogue so aged it smells like Sardinian maggot cheese. Faced with a row of coffins containing several of her assassinated agents, M (Judy Dench, once more) glares into the middle distance and sternly announces, “I’m going to find out who did this.” Well, yes, that’s your job, isn’t it? I also appreciated the scene in which Bond clasps the hand of a killer he’s just pushed over the edge of an elevator shaft. As the dangling man’s grip weakens, Bond demands, “Who do you work for?” Don’t count on the malefactor answering before he splats below.

There are more disappointments. Intuiting that a seeming femme fatale is actually a victim who had been sold into the sex trade as a youngster, Bond promises to help her escape her current owner. In the next scene, he sneaks into her apartment and, finding her in the shower, slips in uninvited. What follows seems to me a questionable remedy to apply to an abused woman. Bond’s earlier incarnations can hardly be said to have been gentlemanly when it came to the fair sex, but, as I recall, not one of them was ever quite so callous.

The film is on better ground with its villains, one of whom is M, who is played as a ruthless bureaucrat willing to sacrifice her agents when expedient. The film opens with Bond bursting into a room in which a fellow British agent is lying on the floor, shot. As Bond attempts to stanch the fellow’s wounds, M talks to him via his satellite-linked earpiece. She angrily insists he drop the poor guy and get on with his assignment. Worst of all, she’s not above quoting Alfred Lord Tennyson at the British intelligence committee investigating her fitness to continue leading MI6. She insists her agency is filled with “heroic hearts, strong in will to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.” I thought I was at a high-school commencement.

Raoul Silva (Javier Bardem) is the other villain, a former employee of M, who treated him as heartlessly as her other charges. She abandoned him to a Chinese jail, where he was tortured unspeakably for years. Silva means to wreak retribution on the old bitch by first killing her career and then killing her. To do so he hacks into M’s laptop, where she improbably keeps the names of all the NATO agents embedded in terrorist cells around the world. Bardem has been equipped with long blond hair and a fey manner, the better to remind us of WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange. Only he’s far more perverse—literally so in a scene in which he questions Bond at close quarters, massaging his counterpart’s thighs and chest admiringly. Bardem gives a wonderfully creepy performance that almost single-handedly rescues the film from its many lapses into the land of cliché.

Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, like Skyfall, comes down to a contest between two men: President Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, Republicans contesting during the last year of the so-called Civil War. Lincoln is committed to a program of quiet guile to win his war and restore the Union; Stevens prefers a rabid, no-hostages-taken assault on all things Southern.

People have and will complain that Spielberg’s film is another worshipful portrayal of the Great Emancipator. There’s no doubt that Spielberg and his screenwriter, Tony Kushner, side with Lincoln: Spielberg has instructed the film’s composer to lay on the violins every time Honest Abe speaks, especially when he’s not being honest. Nevertheless, the film’s dialogue and enactments remarkably conspire to show us just how conniving Lincoln was, using his own words, drawn from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals. This Lincoln admits to breaking the law and traducing the Constitution to get his way. Goodwin frankly admires Lincoln’s duplicity, but as an exposed plagiarist, she likely thinks that getting the job done justifies flouting antique notions of honor.

On this score, Spielberg often seems to be at odds with himself. On one hand, he insists the war was a necessary and noble undertaking; on the other, he shows Lincoln’s proclaimed commitment to the battle to have been hypocritical. When his older son, Robert, insists on enlisting against his wishes, Lincoln makes sure he’s posted to Ulysses Grant, who is instructed to use him as a courier well behind the front lines. (In this, Lincoln resembles our present-day congressional warhawks who make sure their own children don’t risk their lives in the noble cause of spreading democracy in the Middle East.)

Further, we see Lincoln lying to the South’s peace emissaries, including Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, first leading them on to believe he wants to end the war, and then issuing demands he knows will be impossible to accept. At the same time, he lies to Congress, telling them that rumors of the Confederate peacemakers in Washington are unfounded—technically true, since he kept the envoys outside D.C.’s city limits. He fears a majority of the representatives would demand a treaty be made with the Southerners before he can railroad the passage of the 13th Amendment that will officially free the slaves. Nor does he do this out of any moral commitment to the rights of Africans in the states. Although passed over quickly in the film, if you listen closely you’ll hear him say that he doesn’t believe blacks and whites can live together on an equal footing. He hoped to see a solution to slavery in colonization—that is, sending the blacks back to Africa or on to Central America. What was foremost in his mind was reestablishing and then maintaining the Union.

Historians disagree on Lincoln’s intentions. It may be that he wasn’t always entirely clear about them himself. He seems to have realized that his machinations immorally trod on the rights of Southerners. He was unquestionably intent on centralizing federal power at the expense of state and local rights. But this wasn’t entirely a power grab. There were other considerations. If the Confederacy had remained its own nation, America would have been weakened, perhaps fatally. England and Europe were watching events closely. An independent North and South would have likely seemed attractive prey to interested parties. After all, 1860 wasn’t that far away from 1783.

As Lincoln, Daniel Day-Lewis is utterly convincing. He makes the Illinois backwoodsman a sly, secretive, even creepy presence. His Lincoln is a manipulative politician who rarely looks others in the face, preferring instead to regard them sidelong, hiding his real thoughts as he massages their vanity or their principles—it doesn’t matter much which—to get his way.

As Stevens, Jones is a hectoring, insulting loudmouth. He bellows his derision of all who disagree with him. He demands blacks be accepted as unqualified equals. He only moderates what most in his day considered an unforgivably extreme stance when told that he risks losing the vote for the amendment. Then he swears falsely before Congress that his intention is limited to seeing that blacks gain equality before the law. Those who know the history of these events will also know that Stevens’ interest in this fight had an intimate connection. Since the film holds this information back until the very end, I’ll refrain from mentioning the particulars.

Spielberg is honest about Stevens in another context. In a late scene, Stevens tells Lincoln in no uncertain terms that he will lobby Congress to confiscate the land of white Southerners and turn it over to the blacks. He wants nothing less than to bankrupt and humiliate Southern whites. Like other Abolitionists, he hated Southerners unreservedly—a feeling, the film indicates, not shared by Lincoln.

This may be true, but it hardly excuses Lincoln’s insistence on prosecuting the war in the first place and then avoiding proffered offers of peace; 650,000 combatants died as a result, and no one knows how many civilians. And for what? An inevitable economic and political outcome that was already at hand before the first shot was fired. The word shameful comes to mind.

Leave a Reply