Vice

Directed and written by Adam McKay

Produced and distributed by Annapurna Pictures

Wildlife

Produced by June Pictures and Nine Stories Productions

Directed by Paul Dano

Screenplay by Paul Dana and Zoe Kazan adapted from Richard Ford’s novel

Distributed by IFC Films

In Vice, director Adam McKay takes a hatchet to Dick Cheney, joining a long line of detractors of our 46th Vice President. This is too bad. Not because Cheney deserves better. As one of the primary planners of the 2003 Iraq invasion, he clearly deserves whatever obloquy can be thrown on him. But rather than taking a hatchet to his reputation, McKay would have done better to make his case against Cheney soberly and let the facts speak for themselves. Instead, his film gives those determined to see Cheney in a favorable light a means to discredit it. They are already dismissing this film as the work of a political enemy, which it clearly is.

Cheney is a schemer, but then who isn’t in Washington, D.C.? While serving in four administrations, he was continuously focussed on acquiring power. And he found ways to get it. First, he attached himself to Donald Rumsfeld. Later, he attached himself to George W. Bush. Both presented opportunities to increase his influence. As McKay has it, Cheney even divined an opportunity in the September 11 attacks. He joined the neocons in their determination that the United States should invade Iraq. September 11 was the provocation necessary to justify this step. In the film, just minutes after the terrorist bombings, we see Cheney on the phone talking to President Bush, who’s flying back to Washington. He tells the President that he should stay in the air for the time being. It’s a reasonable decision given the chaos on the ground, but it’s also a chance to put into action the neocon 1997 plan for regime-change in Baghdad. Our erstwhile ally, Saddam Hussein, had to go. Once he did, the U.S. would be free to take over Iraq. In one scene, Donald Rumsfeld is shown hectoring his aides to uncover a connection to Saddam Hus sein even as others in the room, Colin Powell principally, are adamant that Hus sein had nothing to do with 9/11. It’s a grimly funny moment and reveals that the fix was in. In 1997, neoconservatives such as Robert Kagan, Richard Perle, and William Kristol had created their Project for the New American Century, drafted PNAC’s Statement of Principles, and began lobbying for deposing Saddam Hus sein. They had reasoned they could acquire the necessary national support for their scheme if only there were a suitable casus belli, something similar to the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. The 9/11 sneak attack fit the bill, and they weren’t going to waste the opportunity it afforded them. It really didn’t matter to them whether the attack on the World Trade Center had been directed by Hussein. What mattered was that it gave America cover to invade and take over Iraq, an oil-rich nation that had been threatening Israel. They reasoned that Americans might not support a war on Israel’s behalf, but they would heed a call to arms if America herself came under attack. And so we were drawn into an unnecessary war that killed some 5,000 American troops while creating an estimated 32,000 casualties; killed at least 600,000 Iraqis; and in its wake left the country embroiled in a vicious civil war between Arab sects, the Sunnis and Shi’ites. It also led to the rise of ISIS.

Of course, the neocons haven’t gone away. Their spokespeople have been recently writing op-ed articles blaming our Iraq troubles on President Obama, who reduced our presence in the country. They’re championing continued war in the region, with Iran promoted to Target No. One. The Iranian mullahs have continued to threaten Israel, and so America must take action.

What prompted Cheney to join the neocon cause and become a signatory to PNAC’s Statement of Principles? Hard to say. He seems to have seen in the neocon movement another source of power. Of course, he might believe in the preposterous theories floated by the likes of Kagan, Kristol, Paul Wolfowitz, and other leading neocons. That’s if he believes in anything at all. McKay raises doubts about Cheney’s political faith in a scene from his early career in which Cheney asks Rumsfeld what they believe in. Rather than replying, Rumsfeld laughs uncontrollably and steps into his office. For Rummy the answer is obvious. The pursuit of power is its own belief. As O’Brien tells Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four, “Always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing, constantly growing subtler.” Could this be Cheney’s motivation? And if so, does he realize it himself? I don’t suppose we’ll ever know.

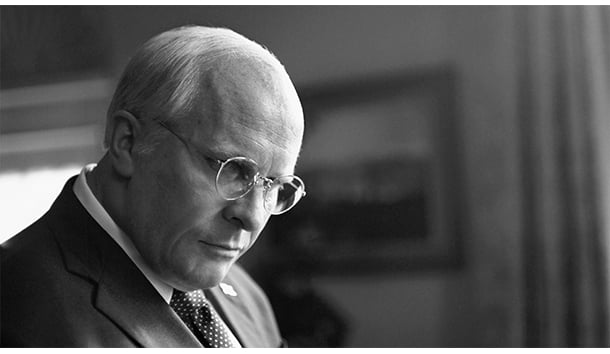

To play the aging Cheney, Christian Bale packed on 45 pounds and had his hair thinned to near baldness. In doing so he achieved an uncanny resemblance to Cheney, but it’s more in the nature of a waxwork simulation. In fact, it’s somewhat distracting as you marvel at his physical transformation while trying to pay attention to his words, which he delivers in the quiet monotone Cheney is known for. Another aspect of his simulation is more successful. He has the Cheney tilt, that characteristic manner in which the Vice President turns his head toward his interlocutors in conversation that suggests he’s sizing up both friends and enemies alike. He’s a quiet watcher, a soft-spoken calculator. This is shown nowhere more effectively than when George W. tries to recruit him as a running mate. At first Cheney says no, but then, under W’s wheedling, he reconsiders. He wonders if traditional responsibilities of the vice presidency could be revised. “Maybe I could handle the more mundane parts of the job. Managing the bureaucracy, overseeing the military, energy, and foreign policy.” Mundane? Who would think these jobs mundane? Apparently, George W. did. Cheney knew his man. Bush was notoriously uninterested in the details of his job and happily let others take up responsibilities that should have been his.

Cheney’s wife, Lynne, also comes in for some drubbing. She’s played by Amy Adams as a verifiable Lady Macbeth egging her husband on to acquire as much political leverage as possible. In one scene, she and Bale speak pseudo-Shakespearean dialogue, so we don’t miss the point. They’re monsters, plain and simple.

I shouldn’t overlook the several scenes that depict Cheney’s heart attacks. As he’s carried off to the hospital, the screen fills with his bare chest, a large bloody hole in it where his heart had been. That explains everything. Cheney is a heartless s.o.b. Well, perhaps he is; but it would have been more telling to explain how he became one. Curiously, McKay never does.

Director Paul Dano’s Wildlife is adapted from a Richard Ford novel of the same title. It’s a grim story of a failed marriage that leaves a young boy unmoored from what had been his seemingly secure life. It’s very good, and quite painful to watch.

It’s 1960, and Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) and Jerry Brinson (Jake Gyllenhaal) have recently moved to Montana with their 14-year-old son, Joe (Australian actor Ed Oxenbould, whose thoughtful performance is the film’s center).

Jerry has taken a job as a golf pro at an upscale country club, while Jeannette is content to be a stay-at-home mother. They seem very happy. But then things begin to go seriously wrong. The country-club manager fires Jerry for becoming too familiar with club members. He doesn’t know his place. It’s an embittering experience that confirms Jerry’s belief that the wealthy don’t want to give ordinary people like him a break.

Meanwhile, there’s a forest fire burning in the hills above their neighborhood, a natural metaphor for Jerry’s predicament. His flaming anger impels him to join the townsmen who have gone off to fight the fire, a decision that Jeanette deplores, especially when she finds out he’ll be making one dollar per hour. “You’ll get yourself killed,” she screams at him. But Jerry wants to do something useful, and this, he believes, is his opportunity.

After he departs, Jeanette takes a job at the local YMCA teaching people how to swim. One of her students is Warren Miller, a man in his mid-50’s who owns a Cadillac dealership. Soon Miller is taking Jeanette out, and what had been friendship turns romantic, at least on his side. At first Joe is bewildered by this turn of events. You can see it in his face and manner. He’s stricken when Jeanette takes him to Warren’s home for dinner. In Miller’s presence, the boy’s speech comes haltingly, and his face registers his profound embarrassment at what his mother is doing. She begins wearing the jeans and cowboy shirts she saved from her teens. She parades them girlishly in front of Joe, asking for his opinion of her appearance. What’s worse, under the influence of too much wine, she openly flirts with Miller in Joe’s presence. This leads to some bedroom antics that she poorly hides from Joe.

What can she be thinking, you wonder? It seems her anger at Jerry for leaving her has triggered her sexual carelessness. She hasn’t any genuine affection for Miller, but his attention flatters her vanity. And, of course, his wealth has its allure.

When spurred on by dissatisfaction and longing, even the most ordinary men and women are, it seems, capable of monstrous behavior. You might call it their step into the wildlife.

When Joe finally finds his voice, he expresses his disgust with his mother’s behavior and waits for his father to return from the forest fire, thinking he’ll expunge the horror that has invaded his life. But can it be resolved? That’s the question the rest of the film will answer.

Dano has given his film a visual design that perfectly complements his theme of a trusting innocent’s profound disillusionment. Joe is almost always in the focal center of each scene as unnerving events swirl about him. It’s the kind of dynamic Henry James liked to explore in many of his novels and stories: an inexperienced child encountering treacherous irresponsibility among the adults in his life. Given the extraordinary incidence of divorce in our era, this is indeed a timely theme.

Leave a Reply