Shortly after the election of 1988 one grand old man of the Republican Party told me he thought Mr. Bush could do a creditable job so long as his administration faced no major crises. The very minor crisis of the abortive coup in Panama was the first serious test of this thesis, and it would seem, at first glance, that the thesis passed and George Bush flunked. Republicans and Democrats alike, liberals as well as conservatives, excoriated the President for his failure to seize the opportunity of ridding the world of a petty drug-dealing despot who had proved impervious to the charm and threats of Elliott Abrams. Congressional Democrats, in describing the administration’s sluggish response to events, revived a favorite term from the Reagan years: disarray, and the Wall Street Journal called the affair another Bay of Pigs.

There could be no more entertaining and edifying spectacle on the evening news than the sight of Manuel Noriega hanging upside down from a window in Panama City, but the same thing might be said of at least a dozen other leaders of our “sister republics” in Latin America. Noriega is no more of a threat to American interests than his mentor, Gen. Omar Torrijos, and it was with Gen. Torrijos that we signed the Panama Canal Treaty. If our main motive in dealing with Noriega is the desire (in Sam Hayakawa’s phrase) to steal back the canal “fair and square,” we ought to realize that there is absolutely no guarantee that the next major or colonel to seize power will be any better than his predecessors.

The Global Democracy hawks had a great time, rattling sabres and hurling threats, and it was just like the good old days to see Mr. Abrams again making tough speeches that sounded as if they had been borrowed from the script of Patton. The tough talk apparently had some effect, and it would appear that some members of the White House inner circle now wish they had done something more to help the would-be freedom fighters. CIA chief William Webster, in defending the administration, more than hinted that President Bush was reconsidering the restraints on covert action that had been imposed by President Ford. While denying that he wanted CIA operatives to become “hired killers,” Webster did argue that a fast and loose CIA could make a difference the next time around, “because the likelihood of the next plotter planning that he may probably take Noriega out is real.” This was enough to bring G. Gordon Liddy back in front of the television cameras, and Mr. Liddy, with his customary clarity, listed a number of assassination targets for the CIA: Manuel Noriega, Jack Anderson (for revealing the names of CIA undercover agents), and CIA turncoat John Stockwell. An even better idea than assassination would be to send the pugnacious Mr. Abrams down to duke it out, man—so to speak—to man with Noriega.

If we could be sure that the CIA employed a hundred Gordon Liddys, all ready to follow orders and keep their mouths shut, covert action—under some extreme circumstances—could be justified as a tool of secret diplomacy. But the whole point to covert actions is that they are covert. Neither the President nor the Congress can be implicated. What sort of spymaster is it, who not only can speak so blithely—and so ungrammatically—about assassination, but does so in the language of cheap thrillers? Webster’s performance as FBI director was applauded by the left as “responsible,” and if he makes the CIA equally responsible, it will no longer have any reason to exist.

Why are we picking on Manuel Noriega? Because he deals drugs. Unlike what other Latin American leaders? Fidel Castro has become a hero in our war on drugs simply by executing a hero of his revolution on the charge of drug trafficking. The newspapers solemnly printed the story that Castro was cracking down on a business in which he is involved, reportedly, up to his armpits. If you believe in Castro, then you may as well believe the stories we used to tell about Gen. Noriega’s heroic war against drugs or, for that matter, the stories we are now telling about this same former friend and ally.

The truth about Noriega is that he has always played both sides against the middle, cooperating with American drug enforcement efforts while receiving payoffs from the drug lords. Reagan appointees in the State Department, whose idea of Realpolitik consists of cliches clipped out of New Republic editorials, were incensed to discover an ally who did not, apparently, live up to the Boy Scout oath. Besides, he was a convenient target—not to say scapegoat: an ugly, acne-scarred hood about to take over our beloved canal. How better to recover their reputations after all their disasters in Central America?

Because it is hard to conceive of our policies of the past several decades as anything but a prolonged disaster. The pattern goes something like this: first we support a hoodlum like Batista or the Somozas, as bulwarks of anticommunism and the American Way (read United Fruit Company); then we dump our ally in favor of a revolutionary party that claims to be fighting to establish democracy; then, when the revolution is successful, Fidel or Danny turns out to have meant not the liberal socialism of Harry Truman but the more virulent form of democracy whose first name is “people’s,” and we begin to support a rabble of ex-thugs, liberal college professors, and ne’er-do-wells whom we choose to call Freedom Fighters—but never to the point that they can win. The last thing we ever wanted was for the Nicaraguan Contras to win. We only wanted to put them into a better position to negotiate.

At the same time, we are attempting to bribe our way into power in Panama, Costa Rica, and El Salvador by funding the opponents of a leftist gangster (Noriega), a liberal democrat (Oscar Arias), and a militant rightist (Roberto D’Aubisson). As it turns out, the National Endowment for Democracy was not the only financial supporter of Oscar Arias’ principal opponent: Manuel Noriega reportedly supplied the same candidate with a contribution of $500,000. The net result is that the United States is hated and despised by the left, right, and center throughout the region.

The only justification for imperialism is success, and our own record—going back over the century—is a virtually unbroken string of failures. It is hard to decide which political party has dirtier hands, the Democrats with Presidents like Wilson and Kennedy and their crusades for democracy and Alliance for Progress, or the Republicans with William McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt, and Dwight Eisenhower and their eagerness to cater to powerful business interests with a stake in Latin America. (Compared with his predecessors, Mr. Bush is actually doing a good job in Central America by his refusal to get drawn into coups, plots, and revolutions. It is easy for outsiders to say he bungled the job in Panama, but not so easy to declare what we should have done. A cautious wait-and-see approach may well turn out to be the only prudent course.)

Fortunately for our reputation, there have been several American statesmen who refused to accept the proposition that it was in our interest either to embezzle the resources or interfere in the politics of our southern neighbors. In this group belong most of the Jeffersonians, including John Randolph and John C. Calhoun, leading populists like William Jennings Bryan, who was scandalized by the Spanish-American War, and many of the Midwestern isolationists. To a good many of their descendants, the most desirable policy could be summed up in the expression “Fish or cut bait.” Either accept the responsibilities of empire and take over the region by main force and Americanize it, or else leave these poor people alone. Our usual tools of diplomacy—surrogate armies, bribery, assassination—are both dishonorable in themselves and unworthy of a great power. If Gen. Noriega or the Sandinistas are as evil and as dangerous as we say they are, then send in the Marines. Otherwise, we can easily afford to let them rot, setting as powerful a counterexample to the world as the Democratic Republic of Germany.

We should treat the nations of Central America with diplomatic dignity, as befits their status as sovereign states, and should not trouble ourselves with the form of government the peoples of El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama are willing to endure. At the same time, the United States should give them not a penny of loans or credits and let them understand that we shall continue in this policy either until such time as they begin to intervene directly in the affairs of their neighbors, in which case we reduce them to the status of a protectorate, or until they learn to govern themselves with “a decent respect for the opinion of mankind.” If covert actions are necessary, as Mr. Liddy assures us they are, they should be undertaken solely in the American interest and never on such flimsy grounds as global democratism or a crusade against drugs.

Other countries, e.g., France and Israel, can afford to employ terrorism and covert action to accomplish their ends, because their governments have some notion of what it is they want to accomplish. We don’t have a foreign policy; indeed, we never had. We have blundered into most of our major wars either by accident or at the whim of whatever political promoter happened to sit in the White House. The last war undertaken in the manifestly national interest was the Mexican War, and it is interesting to note how many of the great Whig imperialists were against it, including the American Cromwell—Mr. Lincoln.

The very word nationalism has an ugly ring to it, contaminated—as it has been—by the economic and political imperialism that has predominated in both major parties for most of this century. (The Republicans in the periods after both world wars are the major exceptions.) Still, something like nationalism is worth reviving as a motivating force behind all policy-making. Whether we agree to call it nationalism, patriotism, or the national interest, such a principle must be advanced as the first step toward extricating the nation from the tangle of bad judgment and bad faith that has balled up both foreign and domestic policy.

The first and foremost aspect of nationalism is the healthy recognition that as individuals we do not belong to some amorphous mass of “all mankind.” We live, not just in specific families and communities, but also in nations. The nation-state as we know it in modern times may be partly the creation of the last several centuries, but the nation as such was in existence a good thousand years before the Greeks created the polis. Every man, to the extent he is a man, acknowledges some form of national allegiance, whether it is his band, his tribe, his king, or his federal republic. That is among the things Aristotle meant by his declaration that man was a zoon politikon, an animal designed to live in a social and political community. To escape from such political ties, he also said, a creature would have to be either a god or a beast, and there is little evidence of divinity in the UN Politburo.

What is a nation and what is it for? Whatever the members of our Congress may think, it is not, as Treitschke observed, “a debating society.” The German nationalist went on to argue that the political apparatus of the nation, what we have come to call the state, exists primarily for purposes of offense and defense. Whenever liberal and humane goals advance those purposes, they are worthy of consideration, although not necessarily of adoption. The home mortgage deduction, for example, serves to create a stable class of landholding citizen-soldiers vital to the defense of a nation that cannot afford to depend on mercenaries or a ragtag volunteer army. What good purpose our other social policies are supposed to serve is anybody’s guess.

The problem with Treitschke’s formulation is its imperialist ring. As a German preoccupied with German reunion, he had a natural concern with expansion, but it is not clear that under most circumstances the creation of an empire actually serves the interest of the imperial nation. One of the first great empires in our history was the creation of the Assyrians, who strained all their resources in maintaining a losing cause, and it is not clear that the Persians or the British, as nations, benefited in the long run from their conquests. The Romans may be the great exception, although if we can believe the complaints of Juvenal (among many others), the Roman and Italian peoples who created the empire were submerged by the conquered races who poured into Rome in search of “economic opportunity.”

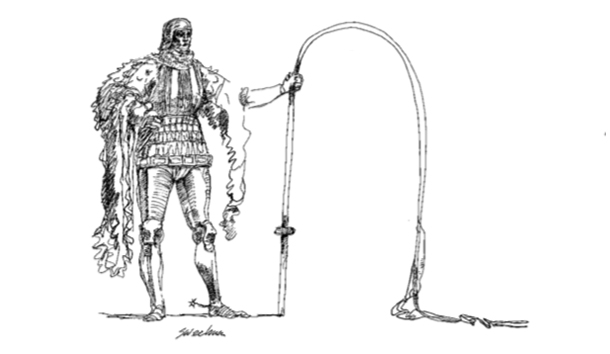

Americans, however, are not made out of the heavy Roman wool or even the cheaper manufactures of Manchester. Our homespun is a kind of cloth that cannot endure a change of climate. Subjected to the heat and damp of the tropics, the national fiber begins to rot. Since there is no point in making policy that does not suit the warp and woof of the national character, we may as well resign ourselves to a policy of armed and militant isolationism and revive our ancient symbol of the coiled rattlesnake: “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Finally, all our national policies—whether they are concerned with trade, immigration, foreign ownership, or nuclear disarmament—must be made with both eyes kept on the main objectives: the security and well-being of the American nation. This is not always the same as the bottom line for American business. Time after time, our government has been dragged into ill-advised foreign adventures on the grounds that it is good for business. Trade follows the flag, we were told, and such a justification was used to defend our repeated incursions into Nicaragua for the benefit of United Fruit. The result was foreseen long ago: the countries whose sovereignty we have most often offended against are precisely the countries in which leftist revolutions have been most successful—Cuba, Nicaragua, and Mexico. For those who wish to learn and relearn the lessons of Vietnam, what was it brought us into collision with the Japanese empire, if not our concern for profits to be made in Southeast Asia? What else was the justification for our involvement in what became the Vietnam War? No more Vietnams ought to mean no more wars undertaken to promote the interests of imperial corporations.

Above all, no more Vietnams should mean no more global crusades to advance democracy, because the more we fight for democracy abroad, the less of it we seem to have at home. This is no paradox. What the great global democrats—the advisors of Presidents Wilson, Roosevelt, and Kennedy—really wanted was a domestic revolution. World War I became the pretext for introducing a command economy and economic planning (as both William McNeill and Murray Rothbard have pointed out); World War II was converted into a crusade for equality, civil rights, and the Welfare State; and the cancer of imperial government never grew as rapidly as it did in the Vietnam years.

Even the best-intentioned crusades go awry. The postwar anticommunism, around which so many decent conservatives and liberals rallied, has been turned into a terrible machine that exists to raise money and polarize Americans against each other. Mesmerized by the spectre of global communism, we undertook to impose loyalty oaths and to devise an orthodox ideology of social democracy every bit as rigid and preposterous as Marxism. One leading conservative announced to the Philadelphia Society several years ago that America needs anticommunism as a force to hold the nation together. This means, in practice, the sort of siege mentality that can justify almost any abuse of power. Marx, who once defined ideology as a set of principles used to defend the interests of a ruling class, must have been smiling in his beard.

Now that anticommunism is fading away from the scene as an integrative ideology, ideologues are floundering about in search of its replacement. Some have hit upon the temporary expedient of a drug war; others have projected a more long-range crusade for democratic globalism, while still others have opted for a no-limits-to-growth Utopian model of the global marketplace and economic interdependence. Conservatives of the postwar generation that is coming to power will have to learn to recognize that globalism is only a dishonest synonym for the old imperialism that has almost succeeded in destroying the old republic. The old ideals of limited government and free enterprise, combined with the statecraft of the rattlesnake, are still the best weapons against the banana republicans of both parties.

Leave a Reply