The controversy over the humanities curricula is a struggle over definition, and what is at issue is not so much the nature or purposes of the American university as the identity of the American people. There have been many such definitional combats in the past; the greatest of them led to the War Between the States. In all such struggles, whatever the nature of the dispute, the real object is always power. No one knew this better than Lewis Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty. After defining “glory” as “a nice knock-down argument,” he explains to Alice: “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean-neither more nor less.” When Alice politely suggests that the question is, whether one can make words mean what you want them to, Humpty Dumpty replies rather brusquely: “The question is which is to be master that’ s all.”

It is obvious, then, that in attempting to define both multiculturalism and the arts, we arc involved in a struggle for power, and the question is which is to be master in the universities, in the culture at large, and ultimately over the American future. One immediate problem in such a discussion is that both terms—multiculturalism and the arts-are more political slogans than good Old English words.

The first term, multiculturalism, is nothing more and nothing less than the latest rallying cry for all those who object to European man’s European bias, although they have no objection to such bias whenever they find it “among oppressed peoples struggling to assert their identity.” Indians, Africans, and Latinos; women, homosexuals, and defectives all have a right to their particular point of view, to a literature that can only be interpreted by members of the group, and to a curriculum based on their peculiar literatures.

In saying this I am far from deprecating the legitimate aspirations of Latinos, Indians, blacks, and others to express their ethnic and cultural identity in novels, painting, and music. On the contrary, true ethnic patriotism seeks its own self-expression and not the subversion of another culture. I think of the original platform of the Parti Québecois, whose leaders wanted home rule for Ouebec and the local assertion of French language and culture. Unfortunately, what the Canadian liberals gave them was a national policy of bilingualism that imposed French on Cambodian immigrants to Winnipeg without yielding a drop of self-determination to the Quebecois.

The other term, “the arts,” is no less political. Oh, the Romans used such expressions as artes liberales-translating literally from the Greeks’ technai eleutheriai-and bonae artes and artes humaniores to refer to the various components of sound education: the study of grammar, rhetoric, literature, history, and philosophy. However, used without qualification, “the arts” has come to mean not just the high arts of literature, painting, music, and sculpture; it now comprises everything from Rembrandt to the ceramic ashtrays my daughter made in second grade, from Sophocles to striptease.

Let me then clarify what l mean when I say arts. I mean principally what the Greeks, Romans, and civilized Europeans have meant by artes humaniores, that is, literature conceived of in its social, political, and educational aspects, and among works of literature I am including, in addition to poetry, fiction, and drama, the classic works of history, oratory, and philosophy. By extension, I am free to appropriate the fine arts of painting, sculpture, architecture, and music insofar as they fulfill the same functions.

Art may fulfill higher purposes than these, but since multiculturalism concerns, as I have said, national identity, it is a question to he addressed by us not as individuals enraptured by Mozart or Mallarmé but as members of our society. As a result, it is the social and public aspects of the arts that we have to consider. The task is not to appreciate the glories of Titian and Pindar, but to examine the humbler and more utilitarian matter of art’s social functions.

In my last sermon on the purpose of literature (August 1992), I argued that it is by telling that we make moral sense of the world and pass down the deepest principles of our civilization to the wild animals we treat as human beings in the hope that they will someday live up to our expectations. A “classic” in this sense is not merely a work written in a classical language or even one that exhibits’ the qualities of construction and style of the best ancient works. A classic work ought to be an indispensable text of our civilization in the same way that a book of the Bible is not only supposed to teach what is true; it must also be a unique source for an important piece of doc trine or historical information.

I dislike the notion of a canon, because such canons tend to be drawn up by hookworms and so-called literary critics who arc really the ghouls and vampires of culture, the undead who prey upon the living in order to give their putrifying souls the illusion of vitality. As formulated by Alexandrian scholars, the original canons were an attempt to sort out the best of local Greek literary traditions in order to lay the foundation for a Panhellenic culture. It was also of some importance to kick out the cuckoos that had been fobbed off on important writers. But once the notion of a canon was diluted to mean nothing more than the books that a current consensus of English professors like to teach, once it included recent works of popular fiction as well as works intended to flatter this nationality and that minority, the canon lost all usefulness. Jane Austen and Scott Fitzgerald arc writers that have given me a great deal of pleasure, but in what sense arc they indispensable? For several generations now, at least since the creation of the first English departments, “the canon” has been a tool of cultural hegemony for several generations of critics, whose dream, borrowed from Matthew Arnold, was that culture could replace religion, literature take the place of Scripture, and-most important-that English teachers assume the mantel of priests and prophets. I say English teachers, because an “English scholar” is a contradiction in terms, outside of a few fields like Old English philology and textual criticism. It is time to abandon canons and fall back on looser and more general terms, such as “the classics,” or “really significant books.”

There really is very little doubt about the most significant books of the three Western millennia. The Iliad and the Aeneid are two out of perhaps two or three do1en essential books that formed our civilization. Even the German barbarians of the early Middle Ages heard rumors of these talcs, and since the days of Petrarch schoolboys have been taught their Homer and Xenophon and Demosthenes as well as their Vergil, Caesar, and Cicero. The civilization we generically la bel as “Western,” is in fact a composite of several tribal traditions: the stories of the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Hebrews coalesced into the high culture of Christendom, but these fruit-bearing branches were grafted onto the crude and hearty stock of barbarian Europe-Germans, Celts, and Slavs-and despite the great differences between the cultures of Florence and Paris, and the still greater differences between London and Belgrade, the cities and nations of Europe were united in regarding the biblical and classical inheritance as the foundation of their civilization. To these were added the great national classics of modern Europe: Hamlet and Don Quixote, Dante’s Commedia and Goethe’s Faust.

Here, if you like, is a multicultural banquet that might be used to illustrate the motto of the United States: E Pluribus Unum. Every student of the classics is, in fact, an expert in comparative literature, since he has been trained to compare two quite different cultures both to each other and to the modern world.

An educated man of 1900, whether his profession were law, medicine, divinity, journalism, business, or the army, had something more than football or the weather to discuss with his friends in other professions. Latin had been drilled into all of them, as well as ancient history. Most had some Greek, and if they didn’t, they pretended to. Knowing Latin, they al so knew English as very few know it today, and all had picked up more than the rudiments of one or two modern languages. When they made their once in a lifetime trip to Italy or France, they were prepared to make some sense out of what they saw. English and American books they mostly read out of school and for pleasure. Paradise Lost is written in an un known tongue for those who know no Latin and are unfamiliar with Vergil, but to our ancestors Milton presented few problems-nor did Shakespeare or Sam Johnson. In the 1990’s, however, we must tell a different story, when the aver age literature major can hardly read anything written before this century.

The classical curriculum was not chosen at random; indeed, it was not chosen at all. It grew by a process of trial and error and for nearly three thousand years of sifting and sorting, pondering and reflecting upon the histories and experiences that we, as civilized Americans, would have a right to claim as our own. fore exotic literatures-Byzantine histories, Serbian epics, the Hindu Vedas, and Confucian analects-were left to specialists and amateurs. A Pole who moved to London would naturally want his children to know something of their heritage, but he would not want this specialized knowledge to substitute for the general learning that allowed educated Poles and Englishmen to communicate. One child of the Polish Diaspora became a competent minor poet in English (Theodore Wratislaw), and an immigrant Polish sailor be came one of England’s greatest novelists. In France, the Latin American émigré Jose Heredia became a major French poet of the Parnassian school, and in more recent years the Irishman Samuel Beckett and Julian Green of Savannah, Georgia, have made major contributions to French literature. The literary successes of these aliens were possible, because of the cultural continuity across the European world and over the European centuries, and this continuity is summed up in the old curriculum.

The function of a general curriculum-whether it was our own classical course or the Sumerian and Akkadian texts that ancient Babylonians and Assyrians had to master-is always the same. IL is to teach us who we are as a people and to impart the wisdom that is necessary for life within the tribe or nation. Every society has rub and. regulations that must be learned: which fork to use for salad, what to do with a finger bowl, where to put your arms when you’re not eating-in Britain and the States we must not put our elbows on the table, but in France and Italy it is bad manners to put your hands in your lap.

I have read of a society in which breaking wind at dinner was a very serious offense that could be overlooked only if everyone present pretended not to notice, but if anyone laughed, the unfortunate dyspeptic had to leave the table and commit suicide. These are rules one needs to know, and there arc thousands upon thousands of them, regulating our morals, manners, politics, and law; they are most often taught either by direct example or by means of songs, poems, stories. Few of them are put into Emily Post or the Constitution. Chris Kopff likes to insist that the constitution of the United States declares that no admitted atheist can be elected President. Of course, he doesn’t mean the piece of paper drawn up by Madison and his friends, but the unwritten law.

In Europe and the United States, the rule-bearing songs and stories comprise Western literature. Our tribal rituals of initiation were a prolonged education in the languages, histories, and literatures of Europe. When these stories are no longer known, we shall disappear as a people-or rather as peoples. Mario Vargas Llosa in his novel The Storyteller portrays a Peruvian tribal people on the verge of extinction, but they are held together by the efforts of a traditional story teller, who is actually an urban Jewish intellectual who has adopted their culture. This sort of adoption is rare, almost nonexistent outside the West, but our culture and languages have found some of their most eloquent defenders in refugees from other cultures: Sam Hayakawa the linguist and V. S. Naipaul, an Indian from Trinidad. (In Camp of the Saints, Jean Raspail’s apocalyptic novel of immigration, one of the last defenders of France is a Hindu with his old tiger rifle.)

The classical curriculum endured, virtually intact, clown to the end of World War I. By then reformers like Harvard’s President Eliot and John Dewey of Columbia Teachers College had succeeded in designing a revolutionary curriculum to change the character of the American people. The old curriculum was elitist, undemocratic, and impractical. What they put in its place was a hodgepodge of social theory, propaganda in the guise of history, a handful of American novels, and at the best schools a one- or two-year survey of Western Civics that was straight out of 1066 and All That or Mel Brooks’ History of the World. By the 1950’s college-educated Americans were proverbial for their ignorance, and by the 1970’s average American college professors had less general learning than the students of the 1930’s. I been there.

You will forgive me if I do not waste my breath defending the postwar status quo. The curriculum reforms of Eliot and Dewey were the liberal phase of a revolution that is inevitably eating its children. The liberal reformers played the part of Mirabeau and Kerensky; their principal function was to destroy what had existed in order to pave the way for the Jacobins, Bolsheviks, and multiculturalists who were willing to carry their logic one step further.

When the advocates of multiculturalism attack the status quo, they meet with only token resistance. At Stanford, the defenders of the old humanities course want to hold onto the classics because they can be used to teach the students about the evils of racism and sexism, and many of the opponents of multiculturalism arc not even members of the civilization they think they arc defending. In general, “the conservatives” seem to be less educated than “the liberals.” Oh, but they arc well-intentioned, I am told, but it is these sorts of intentions that arc the building blocks of the hell we have already made of our universities. A well-intentioned carpenter builds houses that fall down on the heads of the inhabitants, a well intentioned minister preaches heresy and seduces children, and well-intentioned social workers make war upon the poor. No, give me a malevolent carpenter who knows his business or a well-educated Marxist.

In literature the liberal curriculum has proved to be a dis aster. It has meant the abandonment of critical standards, the loss of all measures of excellence-including craftsman ship. It has also produced two generations of clumsy ignora-muses who, whatever their talent, will never rise above the level of the creative writing seminar and will never produce anything more than what Donald Hall has called the McPoem. Literary modernism is more or less extinct and only survives on the basis of government grants and MFA courses. Shouldn’t we be asking why Alexandra Ripley gets millions for her sequel to Gone with the Wind, while critically acclaimed poets and novelists have no readers beyond their friends?

You will say that it took Eliot, Pound, Joyce, and Faulkner years to find their audiences. That is true, hut the late Del more Schwartz has yet to find his, and if poets like John Ash bury ever find an audience it will only be in the Levittown suburbs of Dante’s hell.

The great modernists were all classically trained. Eliot learned Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit at Harvard-to say nothing of the French, Italian, and German he picked up. Pound, in his sketchier, more chaotic manner did the same and went on to dabble in Chinese. Robinson Jeffers got the full treatment in Germany, and even Raymond Chandler owed his literary taste and craftsmanship to his schoolboy indoctrination into Greek and Latin. Is it some strange accident that the founders of modernism, all of whom wrote difficult books, had a popular appeal in the 30’s and 40’s?

The reasons for this are two: in the first place, their training gave them the ambition and the ability to write masterpieces; secondly, there was a general readership of reasonably well educated men and women, who might not get all the references in Ulysses or The Cantos, but who did not regard Homer and Dante as terra incognita.

The great experiment of modernism was an attempt to affirm continuity with the classical and Christian past and to repudiate the shoddiness and insincerity of a commercial and liberal culture that was in the process of committing suicide. Let me read from perhaps the greatest of these indictments, Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberley:

For three years, out of key with his time,

He strove to resuscitate the dead art

Of poetry; to maintain “the sublime”

In the old sense. vVrong from the start-

No, hardly, but seeing he had been born

In a half savage country, out of elate;

Bent resolutely on wringing lilies from the acorn;

Capancus; trout for factitious bait;

Idmen gar toi panth’ hos eni Troiei

Caught in the unstopped car;

Giving the rocks small lee-way

The chopped seas held him, therefore, that year.

His true Penelope was Flaubert,

He fished by obstinate isles;

Observed the elegance of Circe’s hair

Rather than the mottoes on sun-dials.

How many English professors can read this without footnotes? In a letter to his mother Pound himself prophesied that “the art of letters will come to an end before A. D. 2000.” The train of progress, so far as I can tell, is running on Pound’s schedule.

There have been various attempts to distinguish highbrow from lowbrow culture, erudite from popular art, redskin from paleface writers. All of these distinctions have some validity, but I believe that all the greatest art is ultimately folkish or popular in origin and inspiration. Shakespeare was the tribal storyteller for Elizabethan England, and more than one English statesman has taken his view of his country’s history from Richard II and Henry IV.

For those of us who are or ought to be heirs of Athens and Rome, of Florence and London, our folkways include the tribal stories of many peoples. The failure to hand on these languages and stories has reduced our writers to the level of our barbarian ancestors-with this very important exception. The Goths and Franks and Saxons all lived in coherent tribal societies with strict moral and social codes as well as standards of craftsmanship and aesthetic conventions. Anyone who has glimpsed the Sutton Hoo treasures in the British Museum or the Merovingian tombs in France will recognize the power and creativity of these barbarians. But we, cut adrift from our anchors, must sail upon the waves of commercial mass culture, and if I say that much of the best art of the past thirty years is to be found in film and popular music, I do not mean it as a compliment to Martin Scorsese and Lou Recd.

Good art, to say nothing of great art, is not created in a vacuum. It comes out of a context and it is created within a tradition. Thomas Love Peacock’s complaint that “a poet . . . is a semi-barbarian in a civilized community” is only the negative way of saying this, because the poet and painter bring us down from our penthouse apartment of global markets and world government to the primitive facts of life, love, desire, and hate; art puts us back in touch with that part of ourselves that remains in the childhood of the human race. If art is tribal, then my art must be the art of my tribe, and that tribe is classical and biblical.

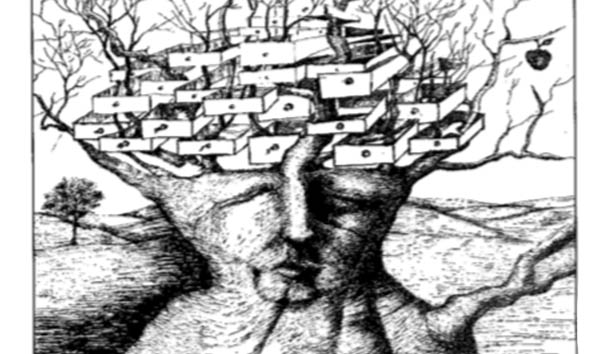

The Greeks told the story of the giant Antaeus, whose strength was invincible so long as he remained in contact with his mother earth. In order to destroy him, Hercules had to rip him up from his source of power. Cut off from the deepest and most ancient roots of our civilization, we of the West grow too feeble to defend ourselves.

Much of what I have said about cultural tribalism applies with equal force to the cultures of Oriental and African peoples as well as to indigenous Americans. If there are Chinese or Zulus or Hopi who wish to preserve and celebrate their cultural traditions, I salute their efforts and wish them nothing but the best, so long as their art derives from a love of their own people, rather than a hatred of mine. What I ask them to grasp is what I call the Golden Rule of nationalities. If it is right, as I believe it is, for Americans to want to put America first, then we must extend a similar privilege to the French, to Croatians, to the Khmer, and if Oriental or native American residents of this European colony wish to celebrate their traditions, then it ought not to be at the expense of mine.

The reality of the situation is quite different from what I have described. for the most part, multiculturalism is a war against the culture of the West and the institutions of American life. Back in the 60’s it was common to say that the history Indians, lynching negroes, and abusing women. This was said not by Indians or blacks or women but by white male liberals.

“A liberal,” said Robert Frost, “is someone who would not take his own side in an argument,” and this wise saying accurately describes the multiculturalism debate in which European-American scholars will not tell the truth about such fraudulent books as Kirkpatrick Sale’s Columbus or Martin Bernal’s sci-fi travesty of scholarship Black Athena, or Alex Haley’s Roots, a book that purported to be a true family his tory, although the author plagiarized some parts from a novel.

We are perhaps the only civilization in the history of the world to perish, not at the hands of its enemies or as a result of its vices. It is our virtue that is destroying us, our Christian zeal to save the world, our rational insistence upon seeing the other man’s point of view. We assume that our values of rationality, self-restraint, fair play, tolerance, and the rule of law are universal. They are not nor should they be.

We have forgotten that we too are a tribal people with an exotic culture that we have generously opened up to the entire world. We have forgotten that our primary responsibility is to defend our interests and safeguard our inheritance. Instead, we are wantonly destroying it, as much as Cromwell’s soldiers and the French Jacobins who toppled statues, shattered stained glass windows, and stabled their horses in cathedrals. So far from taking our own side, we cannot even remain neutral but insist upon slandering our ancestors. In Nebraska, I am told, they have removed the portraits of Washington and Jefferson from the state house, because they, like so many of our Founders, were slaveholders.

I do not know what can be said of a culture that tolerates, no encourages this combination of lies and self-hatred, except this: no good thing has ever come out of hatred. The creative force of man is in his capacity for love; this springs from his love of family and friends and neighbors and may eventually spread to his nation or even the entire human race. To love your own people naturally leads to that devaluation of others we call xenophobia, but the true name is philophilia love of one’s own people. To love one’s family and neighbors and ancestors more than a set of unknown strangers does not require explanation. The really bizarre and pathological sentiment of the modern world is not xenophobia but the misophilia that makes us like vV. S. Gilbert’s “idiot who praises in enthusiastic tone all centuries but this and every country but his own.” Literature has its origin in the celebration of heroic deeds, of beautiful women, of the glory of gods. The literature of hatred and envy, such as there is, at best rises to the height of satire. More typically it sinks to the level of Mein Kampf or Soul on Ice.

I do not know what the future holds for America or for its culture, but I will venture one prediction. If the current rage against our European culture continues, there will come the inevitable backlash. If there is to be black power and red power, black culture and yellow culture, black rights and homosexual rights, the less educated and less liberal classes will begin demanding white power, white culture, and white rights.

Ethnic hatemongers like Louis Farrakhan, Meyer Kahane, and David Duke may only be the first course in a long banquet of ethnic strife that is to come. And in the reassertion of whiteness, all the gentle virtues of our civilization will perish along with the humane lessons our ancestors learned from contemplating the fate of Trojan Priam.

Leave a Reply