The Vice President was in Russia in September, trying to persuade Boris Yeltsin to amend legislation giving the Russian Orthodox Church a privileged position. Al Gore was just the man to explain religious toleration to the Russians. In the 1996 campaign, he revealed himself as an affirmative action fundraiser, willing to solicit donations from anyone, regardless of race, creed, national origin, or the laws of the United States.

The Russians were unmoved by American protests, arguing that other U.S. allies (e.g., Saudi Arabia and Israel) have established religions and pointing out that pluralism is not one of their religious traditions. Exasperated with Russian obtuseness. Gore told reporters that he had “tried very hard to explain exactly why we Americans feel so strongly about this.”

How strongly Americans “feel” about religious toleration is not a question that can be easily answered. The usual arguments—that America was founded by people seeking freedom of conscience—is as big a lie as anything included in the National History Standards. Some of us came looking for gold or, more often, for free land; and those who did come for religious reasons were looking for some piece of ground where they could establish their own brand of piety as the exclusive creed. In the beginning, virtually every sect made as much trouble for religious rivals as it could. The Yankee Puritans were the most brutally intolerant, but even the Philadelphia Quakers, in their own style of passive-aggression, refused to take steps to protect the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who settled the Pennsylvania back country. If Indians went on a spree and wiped out a settlement, the Quakers blamed the Calvinists and defended the Indians as harmless children of nature. Maryland Catholics did tolerate Protestants, but that was a condition of their settlement.

The most significant movement toward pluralism was made in South Carolina, where an Anglican ruling class had to reckon with a numerous and well-organized Calvinist opposition. The balance in the colony then changed with the arrival of Huguenots from France. Although they were expected to join forces with their Calvinist brethren from Britain, the Huguenots had eaten their fill of religious strife and were content with the right to use a French version of the Book of Common Prayer.

Religious toleration was a kind of inevitable necessity imposed by life on the frontier. The constant threat of attacks by French and Spanish Catholics (to say nothing of Indian devil worshipers) inspired a sense of camaraderie among Protestants which, in the Southern states, spilled over to include Catholics as well. The Hibernian Society established in Charleston at the end of the 18th century was a collaborative venture of Catholics and Orangemen, and Grady McWhiney has pointed out that many early Irish settlers were not Protestants but Catholics who, coming to a wilderness without priests, decided to make do with the other Irish religion.

If the spirit of toleration only took root in America by accident, it remains tine that religious pluralism (at least since the edict of Milan) is a phenomenon peculiar to Western Europe (particularly Great Britain) and North America. It was not always so, of course. The English and Scots were excellent persecutors, and Henry VIII, lovable butcher that he was, burned Lutheran and Catholic with equal zest—the one for his heresy, the other for his treason. The English Civil War was the worst religious conflict between the 30 Years’ War and the Vendee (when the revolutionary government in France waged a war of extermination against the Catholics). The English quit persecuting only when the ruling class, in the course of the 18th century, lost its faith.

If Puritans, Anglicans, and Baptists learned, almost by accident, to endure each other’s presence in the New World, imperial Rome was a precursor of modern states that are tolerant by deliberate policy. Roman citizens were free to believe anything they liked and permitted to practice virtually any religion. The most notable exceptions to imperial multiculturalism were Druids, who performed human sacrifices, and the Christians whose enmity to the human race supposedly drove them to commit even viler abominations. The Empire was tolerant precisely because Rome was no longer the religious nation described by Polybius, who attributed her success to the ingrained piety of the Roman people. During their rise to greatness, Romans were severe against those who taught newfangled philosophies or took part in exotic cults, expelling the former and executing (on at least one famous occasion involving bacchanals) the latter.

True believers can never be entirely tolerant, and it was a sign of flagging enthusiasm rather than charity when American Protestants began thinking kindly of Catholics. The leftist answer to this sort of argument is an ironic shrug of the shoulders. For people like Christopher Hitchens, religious freedom is merely an excuse for dismantling Christian institutions—along with the other artifacts of the old order, such as good manners, respect for women, a sense of honor. Hitchens displayed his contempt for all these “feudal” remnants when he provided the color commentary for the funeral of Mother Teresa.

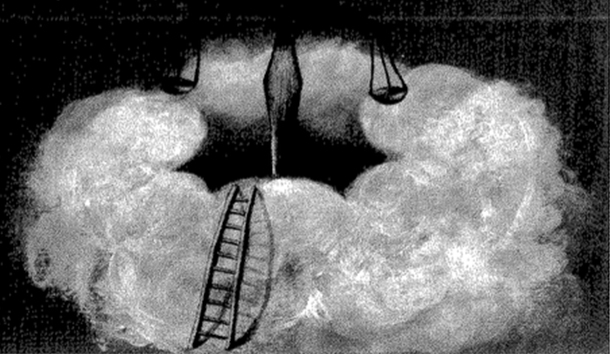

For many professed civil libertarians, freedom of religion is only a tactic. Their real object is the old Jacobin desire to found a new religion of anti-Christianity. The followers of Robespierre staged a bacchanalian festival of reason to inaugurate their worship of the Supreme Being (a god made in the image of the “incorruptible” leader himself). Here in Jacobin America, we have established a counter-Christian calendar. We celebrate the earth goddess during National Women’s Month, pay homage to the proletariat on Labor Day, revere the state on le 4 juillet, and pay perpetual adoration to the ghost of the deified King.

More moderate civil libertarians—Girondists, Kerenskys, and country club Republicans—see religious freedom as an end in itself rather than as one phase in the revolution (which is what it is). Pete DuPont, appearing on C-SPAN, compared the Russian law to protectionism in the United States. I hope Governor DuPont never has to campaign in a Greek or Russian neighborhood; Orthodox voters might not appreciate the comparison of their religion to an aging rustbelt industry.

Most Americans are firmly convinced that everyone in the world is just like them, except for minor differences of hair-coloring and table manners. I have several times nm into otherwise intelligent businessmen who thought that learning Russian would be a snap, because the only real obstacle was the Cyrillic alphabet. Governor DuPont naturally assumed that Russian clerics were as weak-kneed and defensive as an American Methodist and was shocked to discover that Russian Orthodox priests actually liked the idea of a church establishment.

No one, fundamentally, likes competition. We would all like to bet on a sure thing—a rigged wheel, a fixed race, inside information —and there is hardly a Christian church or sect that has not toyed with the idea of establishment: Anglicans and Puritans in Britain and America, Calvinists in Switzerland and Scotland, Lutherans in Germany (to say nothing of Orthodox and Catholic establishments). Smaller sects, even when they do not achieve political dominance, are sometimes more socially predominant than established churches: the Mormons in Utah are the most obvious example, but the Amish and Mennonites are subject to a strict, even oppressive, theocracy.

According to Alain de Benoist and his followers, Christianity is inherently intolerant, always tending toward theocracy and persecution. So far as the clergy is concerned, Benoist is quite correct. Their church is their profession, and if they have any integrity, they are naturally inclined to eliminate not just heresies, but any challenge to the church’s authority. The only honest motive for ecumenism is imperialism, the desire to gain some measure of control over the other fellow’s church. The usual blather emanating from the World Council of Churches —about mutual trust, the common values and traditions of all Christians, etc.—is only a confession of impotence and infidelity. Some Orthodox leaders have tried to persuade their churches to secede from the WCG, and it will be a happy day for Christendom when they succeed.

But the church is not the only human institution with a divine mission. Political authority, as Paul and Luther were fond of reminding us, also derives from God, and the tension between Pope and Emperor, Patriarch and Czar, John Knox and the troublesome Scottish lords, is fundamental to a Christian order. Of course, every church likes to think it has the model system. Catholics condemn the Orthodox establishments as “Caesaropapism,” while Protestants despise the Catholics as priest-ridden. (By the way, I don’t know of any groups so priest-ridden as the servile followers of charismatic evangelical leaders.) But perfection is not to be sought here on earth, even in the far-flung provinces of the Kingdom of God that claim to represent the Church Universal.

The most that a cautious man might say is that we have the churches we deserve. Russian Orthodoxy is too brilliant and gaudy for our severe, Genevan taste—”caviar to the general”— but the Russian soul will never be nourished on law and gospel sermons and four-square hymns on a five-note scale. When the United States produces a Dostoyevsky or even a Rachmaninoff, it will be time for our clergy to go off on a raid to steal the Russian sheep.

Leave a Reply