“The whole world, without a native home Is nothing but a prison of larger room.”

—Abraham Cowley

His father used to say that the country was good; it was only the people that made it intolerable. Now his father’s son was headed up to that north country, where he had not lived for 40 years. He had been back, several times over the years, fishing for trout on the Brule River or trolling for walleye on the Chippewa Flowage. He had visited the desolate city of his birth several times, and once or twice looked up old neighbors or called a school chum, but most of the neighbors were dead, and the chums were off making new lives in the Twins.

No one stayed if he could help it. Once, when he was about ten years old, his mother’s brother, a Coast Guard officer, had come to spend a few days.

“My God, Mary, how can you stand this burg?” he asked his sister at the end of the first day. “There’s nothing here, and the people . . . ” and his uncle went on to talk of the places he had lived—Japan, New Orleans, San Francisco.

Up to that point, he had thought of Superior as one of those cities like Rome or Paris that were known all over the world. With a population of 32,000, Superior covered almost as much ground as Chicago and had the second-largest train yard in the United States. She also had the largest grain elevator, longest iron ore dock, the biggest charcoal briquette plant.

In what other city could a boy walk out the back door of his house and, cutting through a mile of fields where they picked wild strawberries and over hills thick with raspberry bushes, end up in the big woods that led, in one direction, to a sheltered bay of Lake Superior, and, in the other, stretched on endlessly into the great wilderness of the world?

They had spent weekends and sometimes whole weeks at the family’s primitive cabin on Lake Nebagamon. Weeks at the lake began with a trip to the ice house on Winter Street, where it was always winter: Huge blocks of ice were pulled out of the sawdust with hooks and tongs and loaded into the back of the black Oldsmobile 98 for the long 30 miles over country roads to the lake.

At least once during the summer, they went fishing with fake, an Ojibwa fishing guide. Whoever sat next to Jake and did as he was told never failed to catch fish. They took their catch back home to Superior, where Jake would clean and cook the fish. When the boy plagued the guide with his questions, Jake showed him how to make Indian leather out offish skin, and every time he thought the skin was ready for drying, Jake would say: “No, take it over there and scrape it thinner.”

Next morning, his father drove Jake back home, probably to the Lac Court d’Oreilles reservation that runs along the south side of the Chippewa Flowage cast of Hayward. Hayward was once a logging town proverbial for its roughness; now it is as sweet and insipid as the “home-made” fudge its residents sell to Illinois tourists, as suburban as Minocqua.

Driving north from Illinois with his friend from Mississippi, into the green-swelling hills of Southern Wisconsin, he remembered how in Douglas County they had looked down on the lower part of the state, where people in Milwaukee or in prosperous farm towns like Monroe grew soft from gentle winters, rich cheese, and easy living. In the Northwoods, men were tough, and even the massive beer bellies that flopped over the bar were ringed in iron.

Wisconsin leads the nation in per capita consumption of beer and brandy (though much that goes by that name up there would astonish the inhabitants of Cognac), and the northwestern counties, by his estimation, were the most alcoholic in the state. His sampling methods were admittedly primitive, but a man could easily drink his way into unconsciousness simply by having one drink in every bar within a square mile, and a Douglas County pub crawl might take him from the Anchor on the bad side of Tower Avenue in Superior, up the street to the Elbo Room and the Dugout (next to Frankie’s), to the East End and Allouez taverns made famous in the stories of Anthony Bukoski, out to the Kro-Bar and Twin Cables in Brule and down to Finell’s and Bridge’s in Lake Nebagamon.

From the car window, he watched the black loam of Southern Wisconsin him into red clay that thinned out, as they drew nearer to the lake, into coarse brown sand, good only for growing meadow flowers and trees blasted by the force of the north winds that blew from Canada.

At the end of July, the winds came only from the south, and the people of the North Woods were dying in the 95-degree heat. In Iron River, they stopped at the air-conditioned Java Trout, the only internet/espresso bar north of Minneapolis and east of Brainerd, according to the owners. A reporter from the Duluth News Tribune was offended that the owners thought they could make a go of such a place in little Iron River, when there was no internet bar in the Zenith City. There in a nutshell, according to one Wisconsin boy, is what is wrong with Duluth—and Minnesota in general.

At the White Winter Winery housed in the same building, they sampled half a dozen varieties of mead. “An espresso bar and a winery—in Iron River?” he said to the young lady who had set up the business with her husband. “The Green Top restaurant on the highway was the pinnacle of civilization here only five years ago.”

She admitted that their friends back in civilization (greater Milwaukee) thought they were crazy. He told her they had driven up to the mouth of the Brule and tried to come down to Iron River by wav of Oulu, but the road was closed.

“Oulu? Even when you’re in Oulu,” she said, “you don’t know you’re there.” Oulu, it seems, is not so much a place as a state of mind. When he was a boy, his family used to visit a Swedish farm family in Cloverland, and their son Jimmy used to brag of riding his Harley over to Oulu on weekends, and ever since he had imagined the Finns carrying out exotic rituals involving saunas and sacrificial virgins. Perhaps it was only a fishboil.

After the lady vintner and her husband had moved from the civilization of suburban Milwaukee, she decided to run for the school board.

“Someone came to warn me it was not a good idea because there were serious race problems in Iron River. ‘Race problems?’ I asked. Sure, the Finns and Norwegians can’t stand each other.”

Jimmy’s father Donald (who hunted deer with his old man) was married to a Finn. Don loved Finlander jokes and in the late 60’s had taken the exile to the Kro-Bar in Brule (or was it Lyon’s Den?) to see the display of a bowsaw with a chain, instead of a blade, and a 3-in-l can tacked on. The sign read: “Finnish chainsaw wit ta automatic oiler.”

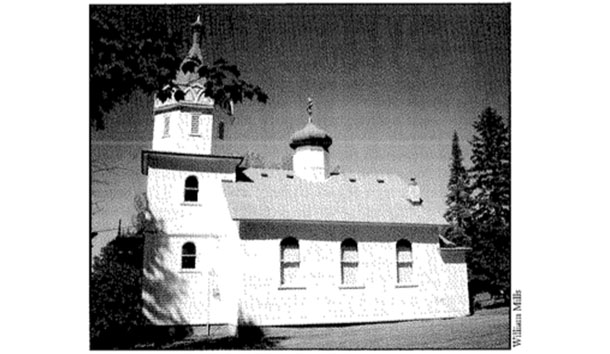

Finns settled Oulu, but Russians went to Cornucopia, a fishing and logging village up on the lake, and although the shoreline has been polluted by a handful of artistes trading on the quaintness of the place, the old Russian church is still there and gleaming with a fresh coat of paint. If Cornucopia is still comparatively unspoiled, Bayfield is well on the way to becoming another Door County or Lake Geneva, a Mecca for day-sailing yachtsmen who every spring toss aside their Brooks and Saks catalogues and order the summer identikits from Orvis and Land’s End. They drove down into Ashland, where Chequamegon Bay had been ruined, like the city of Superior’s shoreline, by industrial and commercial development—the generating plant and coal docks competing with motels and gas stations for the ugliness prize.

Lake Superior has been preyed upon in every generation by foreigners: voyageurs who killed the wildlife in search of pelts for Paris fashions, loggers who clear-cut the forests to build houses in Midwestern cities that went from rawness to decay in the lifetime of one old man, fishermen who nearly wiped out the whitefish population to supply the restaurants of Chicago. Like another interloper—the lamprey eel that preyed upon the lake trout—they sucked the juices out of the place and left behind their ugly scars.

In the morning, they headed toward the Brule to check out the water, which was very high. It was also very hot, especially once he had got into his neoprene waders. He was still hot, walking waist deep against the strong current that sweeps past Winneboujou landing. There was no sign of a tricho hatch that morning; nothing broke the water’s surface. He tied on a nymph and cast out the line, watching it collapse helplessly in wrinkled coils. It had been two years since he had waded a stream, and subsequent casts were hardly better than the first. He checked the line and found he had missed a ferrule and twisted the line around the rod. He cast again and watched the line shoot out smoothly upstream into a riffle; he mended the ballooning line with a flip of the rod and stripped it in with short nervous jerks. If the trout were impressed, they gave no sign. After an hour or so of stumbling into rocks, he gave it up and peeled off the waders to examine his bruises.

Tired of not catching fish, they drove into Superior, and he tried to get his bearings. The jerry-built VA houses had aged as gracefully as plastic furniture.

“I used to wonder about your dark vision of life,” said the Mississippian. “Now I’m amazed at your cheerfulness. What would you have been like if you had stayed here?”

He said he didn’t know but pointed out there were two kinds of people in the world: those who belonged somewhere, those who didn’t. He thought of them as Earthlings and Martiansone of Bradbury’s Martians who can be captured by an Earthling’s imagination and appear to be one of them. He was a Martian, he supposed.

“But a Martian could live in a place like this a hundred years without facing much temptation to go native.”

When they drove across the bay into Duluth, his Southern friend exclaimed over the neatness of the well-preserved downtown.

“Over in Superior,” the Mississippian remarked, “they just sit in the bars and watch the buildings fall down around them.”

“Ought to make you feel right at home.”

In Billings Park, where he had lived, they stood looking at the bay, stained red by the clay washed in by recent rains. An old man got out of a van with a road map in his hand: “Hot enough for you?” he asked in a good Midwestern dialect and told them he had driven all the way from Florida to escape the heat, “As bad as Florida.” Now he was thinking of going farther north. “Stay here,” they said. “It’s just as hot in Thunder Bay.” The exile explained that this kind of weather was impossible so close to Lake Superior. There had been one day of such heat when he was a boy, and it brought on the only tornado in a hundred years. The snowbird looked doubtful and sat down to study his map.

They drove over to Central Park and looked at a gaudily painted house that had been built in the 1890’s as a Unitarian church before becoming, in turn, an AME church and a women’s club. A few blocks away was a rare example of an octagonal house, a style promoted by Orson Fowler, the pioneering phrenologist from Fishkill, New York. Fowler’s obsession with making an efficient use of space blinded him to the obvious disadvantage of his design: No one could figure out how to divide the octagon into livable rooms.

Yankees with bright ideas had been prominent in the early settlement of Superior, but Scandinavia had overwhelmed New England. Glenway Wescott lamented the change wrought by immigrants in Southern Wisconsin, but Superior was defined by the foreigners—the French, after all, had been there first, and the border that ran through the Great Lakes was highly porous to the Scots who pushed their way in from Canada.

They stopped at a bookstore on the outskirts of town to look for books by local writers. “It’s strange to find a bookstore in Superior,” he told the Englishwoman who ran the place. “When I was growing up, people were satisfied with comic books and pulp fiction from Globe News.” (He might have added that best-sellers and diet books were no improvement.) She told him that the store was named after the senior editor of the Literary Guild. Beekman had grown up in Superior and attributed his success in picking books to his knowledge of Midwestern women.

Now he knew what had happened to American literature. Superior took it over and replaced Sinclair Lewis and Scott Fitzgerald with James Michener and Tom Clancy.

Over lunch in the Elbo Room with a local writer, the conversation turned to regional differences. This part of the country was as different from, say, Illinois as it was from Mississippi. Few local people are aware that a Southerner had been involved in the founding of Superior: in fact, John C. Breckenridge, Lincoln’s fire-eating rival in the election of 1860. The Democratic candidate, the pro-Southern Stephen Douglas, also threw his considerable influence behind the project, until his money-grubbing caused a scandal. Illinois is different now: Politicians today are expected to steal.

The writer, who had taught in Louisiana, envied him his life in the Carolinas. Admiration turned to amusement when Rockford entered the conversation. “Jeeze, that’s worse than S’perior.” Going back to Superior, he had made the best of the situation and turned the Polish neighborhood of the East End and Allouez into a literary landscape. It was his Wessex, his Yoknapatawpha, his Middle Earth.

The alien left the two storytellers drinking their lunch and walked five blocks up Tower Avenue to the offices of the Tyomies Society. He had written a dozen newspapers in Northern Wisconsin and received only two responses: one from JoAn Melchild, who writes for the paper in Shell Lake, and one from the Finnish American Reporter, published by the socialist/communist Tyomies Society.

The history of Tyomies is an American saga. The newspaper, which was founded in Massachusetts in 1905 and moved first to Hancock and then in 1913 to Superior, was generally known as the second-largest communist paper in the United States. His seventh-grade art teacher, a rabid anticommunist, spent hours in class denouncing the godless reds of Tyomies, particularly its editor “Mike” Wastila. One day, when the attack on Wastila’s character reached a peak, the boy stood up to testify that Wastila was not a proponent of bank robbery and free love, but was in fact a fine man, his father’s friend, with a wife and daughter who came frequently to dinner.

Although he had warned the editors that he was, for want of a better term, “conservative,” they gave him a warm welcome and a cup of hot coffee to warm him up. Weikko Jarvi, the current editor of the Finnish American Reporter, came to Superior The Russian Orthodox Church in Cornucopi, from the Iron Range in 1958. He was hired by Wastila, who told him he had a job for five years, but by then the paper would be dead. Finns die hard, apparently.

In the 20’s and 30’s, the Society had been instrumental in setting up the first cooperatives, but the movement began to break up over the issue of alignment with the Communist Party. Tyomies was loyal to the party, and they still speak with some contempt for the other side, whom they lump together as Wobblies. (The alien’s mother used to say that IWW stood for “I Won’t Work.”)

Wobblies, socialists, and communists were nothing strange up on the lakes; they were as American as lutefisk and kielbasa. Tom Selinski (not a Finn, but Polish-Slovenian) is making a film on the history of the society. He is bewildered by the Orwellian rewrite of history that demonizes, retroactively, the cooperatives, unions, and leftists as agents of subversion and terror. He blames the “creeping conservatism” of the “trailer court Republicans” who have forgotten their roots. It used to be that when a congressman came to Superior, he spoke at the Labor Temple. Those days are gone.

They are gloomy about the prospects for progressive politics. Thomas Dresel, FAR’s sales director, recalls the visitor from the West Coast who bragged about how much better the co-ops in Washington were—not knowing that the whole co-op movement started in Superior. She probably couldn’t get tofu or organic peanut butter in a co-op run by farmers and dock workers.

Selinski bristles when the 60’s left is brought up to explain why ordinary people turned to the right. “Jerry Rubin wasn’t a leftist,” he says. “He was just Jerry Rubin.” He insists that progressives stand for real family values and defend genuine communities, but when he is challenged on the left’s attraction to homosexual rights, he shifts the ground, asking Weikko Jarvi if the Finns weren’t always in favor of gay rights. Weikko smiles ironically: “No, I can’t say they were.”

Getting down to brass tacks, the conservative asks them why they think they can use government to defeat the entrenched interests of wealth and power. After all, those are the people who own the government today, and Weikko concedes, “That is the problem of socialist countries: The masses are too trusting of the leadership.”

Superior has changed, they say, and not for the better. Hardly anyone speaks Finnish any more, and their old neighborhood—the north end of Tower Avenue down to the docks—is dead. Where there had been shops and office buildings, restaurants and dives, there were now only empty spaces and parking lots for nobody to park in. One of the few buildings left standing in the desert of free parking is 314 John, formerly a house of ill repute that sailors had made famous around the world. Up here, they used to say the meanest towns in the world were Hayward, Hurley, and Hell, but Superior from Fifth Street to the harbor was wild enough to make a fourth. It is all gone now, except for Edna’s place, which the city fathers have preserved, apparently, as the city’s only historical monument.

In the ruins of Superior, the Finns are making an effort to hold on to their heritage: They read the Kalevala, write up stories of their immigrant ancestors, make frequent trips to the old country—FinnAir used to fly directly into Duluth. It is a losing battle. Without becoming Anglo-Americans—playing Hamlet in S’perior would be like performing Mozart in a disco—they have lost the language and culture of the old country.

Give them this, he thought as they shook hands and said goodbye, these Finns had kept their faith when most of the American left was jumping on the imperial bandwagon—or should that be paddy wagon? When Weikko was asked what his first political priority was, he answered without hesitation: opposing war.

Left and right meant nothing anymore, the alien tried to explain. Once upon a time in America, liberals made fun of conservatives who went to church and aped T.S. Eliot. Well, Eliot wrote the epitaph on the best of them today: decent, godless people. Not that the left was any better, and truer. He was sick, he said, of red scares—and of black scares, brown scares, and white scares, too. His father had gone out on the town with Joe McCarthy and pronounced him a good fellow whose worst faults were political ambition and an Irish taste for liquor. Compared with Dean Acheson, McCarthy was a great American, but in pursuing the well-worn path to dictatorship of “divide and conquer,” both the McCarthyists and their opponents set American against American as surely and deliberately as the English pitted Muslims against Hindus in India.

Any dichotomy will serve, if it nourishes the concentration of power: Finns against Norskis, Anglos against Latinos, African against European, left against right. South against North, labor against business. Catholics against Protestants. As soon as the establishment champions Marxism or feminism or minority rights, the fools on the other side will dutifully respond by burning a cross or calling for white identity politics or setting up anti-defamation leagues to protect Catholics or nominally straight males. Americans will do anything but stay home to mind their own business, rear their own children, and cultivate their own minds. Better to stay in Superior, drinking his wav through the long winters, fishing in the spring and hunting in the fall, then ever to get sucked back into worrying about which set of rascals looted the country.

With these melancholy reflections, he walked down Tower Avenue against the hot wind that was being sucked into the changing weather across the lake. He looked up and down the street, trying to summon up impressions from the past, but the effort was futile: It was like a senile husband trying to recognize his wife, thinking, “I might have known someone once, who looked something like this, but she was much younger and prettier.” Above the squalid and huddled downtown buildings, the orange sky was ribbed with clouds bumping uncertainly like a slow freight around a curve. The wind was changing, and it would blow up a storm within an hour. He thought of what a sight he must make: The only man in Superior wearing a jacket and tie, with hair and beard blown wild in the wind—like an anarchist under cover.

He found the good old rebels still making merry in the Elbo Room, and for the sake of health and sanity they ordered a pizza. Nursing their drinks as they waited for their food, they listened to the thunder overhead and watched the people, giggling and wet to the skin, bustling in for dinner. More rain meant high water and bad fishing, but it had also broken the back of the heat wave. They repeated the Finlander jokes they had heard, and then moved on to Polish jokes and redneck jokes. When Wisconsin said he was shocked seeing a Southern tribute to “The Good Darky,” Mississippi rose to the occasion: “We had our problems, but we had a pretty clean record on the Sioux and the Navaho.” When the last ethnic joke is told, there will be five minutes of silence, and then the killing will start. And so it went until late in the evening, swapping insults. Finally, they moved the debate across the street to the Dugout, where the girls were prettier.

“It’s sad,” he heard somebody say. “In five years they’ll be broad in the beam like their mothers. It’s a Celtic curse on the Vikings.”

They had to leave early (it was now 11:00 P.M.) to fish Big Lake on the Brule the next day. When Calvin Coolidge spent a summer on the Brule, the President kept his office at Central High School, where the returning alien had spent the first semester of ninth grade. He wondered aloud whatever had happened to his English teacher, a pretty young woman 40 years ago, fresh out of college and full of life. It was from her that he had learned that words were more than beads on an abacus marking abstract values, that they were more like reflections on water, hinting at the depths beneath the surface and giving a vision of reality beyond the pool itself Chemistry had been his first love, because it went to the essences of things. Words went deeper, he found out at the age of 14 and condemned himself to a life of poverty and inconsequence.

When he came to tell her he was moving at the end of the semester, he thought he saw her crying as he walked away, although his memory might have inserted that detail in later years.

The writer, who knew her as he knew virtually everyone in his hometown, said she had been married—her husband died a year or so ago. He rang her up and put him on the telephone.

“Hello, Miss M.,” he said like an unwelcome ghost. He would have liked to say that the years melted away but they did not. Forty-odd years lay between, 40 years of encrusted irony and resignation.

“It’s so nice when something like this happens,” she said.

“You mean when one of your writing students becomes a writer?”

“No, when they remember their teacher.”

He walked back to the table and finished his beer. It was time to leave before they all started getting maudlin about old times and new friends. The alien promised to come back for the fall fishing, though he knew that the fishing was only an excuse. They stood to say goodbye and left the Superior native sitting groggy and contented at a table in the middle of the barroom in the heart of the Superior he had made the center of his known universe.

Leave a Reply