“Whitman can sing confidently and in blithe

innocence about democracy militant because

American Utopia is confused with and

indistinguishable from American reality.”

—Octavio Paz, Walt Whitman

As we left for Ayacucho, Lucho Monasi Cockburn took out his machete from under his car seat and put it between the two of us. “It’s a bad road,” he said and looked at me. His eyes were blue, almost lost between the wrinkles of his smile. “One cholo less or more, who cares!”

I looked at his machete, in its tooled leather scabbard. “Permiso?” I said and took it out. It was dull and rusty.

“Señor,” said Jorge, as we sat in an Ayacucho hotel bar. “What kind of a country are we, what kind of people?” Jorge was a cholo drinking his 15th bottle of beer. “To your health, Señor,” he said, raising his glass.

“Salud compadre,” I said. “I can see that you are not always happy.”

Afterwards, I listened to Jorge caress his black, worn-out guitar, coaxing her to sound like a blind beggar’s flute—the reed flute of the Andes, which the Indios play to tell the world of their existence.

Then Jorge sang some marineras from the coast, as sad as the mountain music. “Know any Mexican tunes?” I asked him.

“I know everything, Señor, I’m an artist,” he said, and went on singing his marineras.

“The gringito‘s been looking for you,” said Jorge, when we met in Cuzco next night.

“Which gringito?”

“The little one from Ayacucho, who listened as we sang.”

“Oh, Oscar,” I said. “But Oscar’s not a gringo. He’s Peruvian, like you.

I could see Jorge laughing slyly. “Sure,” he said.

In Peru, as elsewhere, people hate each other. Lucho Monasi Cockburn, the traveling salesman, took out a dull machete to defend himself from half-breeds, laughing as he did that, but the quarrel between different sorts of Peruvians was not a lovers’ one. Both Jorge and Oscar hated the Indios for different reasons. The Indians, on the other hand, watched the world impassively, defeated as no other people I have ever seen.

“It all began with a suspicion (perhaps exaggerated) that the Gods did not know how to talk. Centuries of fell and fugitive life had atrophied the human element in them; the moon of Islam and the cross of Rome had been implacable with these outlaws. Very low foreheads, yellow teeth, stringy mulatto or Chinese mustaches and thick bestial lips showed the degeneracy of their Olympian lineage. Their clothing corresponded not to a decorous poverty hut rather to the sinister luxury of the gambling houses and brothels of the Bajo. A carnation bled crimson in a lapel and the bulge of a knife was outlined beneath a close-fitting jacket. Suddenly we sensed that they were playing their last card, that they were cunning, ignorant and cruel like old beasts of prey and that, if we let ourselves be overcome by fear or piety, they would finally destroy us.

“We took out our heavy revolvers (all of a sudden there were revolvers in the dream) and joyfully killed the Gods.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, Ragnarok

I had a feeling that the Indios were forever wordless, their lips like slashes in their faces. Even their children were silent, questioning with their eyes—everyone and everything—without hope, or desire, for an answer.

In Cuzco, I was continually having to make way for overburdened women with children on their backs as they tried to go right through me. They ran with short, choppy steps, contracted into wounded kernels, oblivious to gringos, streets, even the hills of their awesome country.

If Octavio Paz might argue that being white meant being guilty, Borges, the great blind seer of the Library of Babel, would never have done that—an irrevocable European, to Paz’s reluctant acknowledgment of his heritage (Paz: “John Cage is American / that the U.S.A. may become / just another part of the world. / No more, no less”), Borges knew his mythologies.

“The Indios don’t produce anything,” Rodrigo said to me. “Only as much as they need themselves, no more. They are not a part of the economy. They do not consume. I hate them; I hate to look at them.”

“But they are so beautiful,” Marilena said to me, smiling beatifically.

Rodrigo was a strapping young man from Ecuador who lived next to me on the flat roof of Señora Raquel’s Pension in Lima, whereas Marilena was a rich man’s daughter, and a curator of a museum.

Rodrigo and his father, both white, occupied a minute cubicle with enough room for two iron beds and a wardrobe of books. Rodrigo looked forward to studying navigation in Spain, whereas Marilena, a natural blonde, looked forward only to going to the sierra, and feeling good about herself.

As we sat in the great lounge of her father’s house, Marilena listened to my impressions of the Andes. “The Revolution,” said Roberto Ortiz, her boyfriend and my colleague, “is going to change everything. You will see the Indios brighten up and become gaudy like their ponchos and caps.”

“I wish it were so,” I said.

“It will be so,” smiled Roberto. Like a D’Artagnan he stood, his blue eyes flashing. “If Argentina had to go to pot, Peru will not. There’s so much work to be done, hombre!”

“The Revolution,” I said, “I’ve seen it. My father and mother fought in one. My kin died in it, along with many others. Hundreds of thousands were imprisoned, crippled, or humiliated. It doesn’t work.”

“Maybe,” said Roberto, “your revolution wasn’t the right one? Maybe the men who led it weren’t the right people?”

I looked at him. He was smiling—a magnificent gaucho, on the run from the Argentine military. There was nothing I could tell him. I have seen the same obstinate, willful refusal to see in my own Yugoslavia, so we talked about other things.

When Benjamin Linder was killed in Nicaragua at the end of April this year, his left-wing father blamed Ronald Reagan for his death. Benjamin Linder, a Sandinista, had gone to Nicaragua like Marilena, to fill a void in his soul. Whether the contras killed him by accident or design is immaterial. Linder had “placed himself in harm’s way,” and the harm had come to him, as he had sought it. Revolutions mean death, which Linder, as a good American, was unwilling to accept. Daniel Ortega, the boutique-eyeglassed dictator of Nicaragua, attended the young American’s funeral, playing the game that has become obvious to everyone but the American media. As Newsweek ran photos of contras killing a Sandinista with their knives, nobody saw it fitting to remind the American reading public that killing in anger is no worse than the Sandinistas’ methodical “liquidations.”

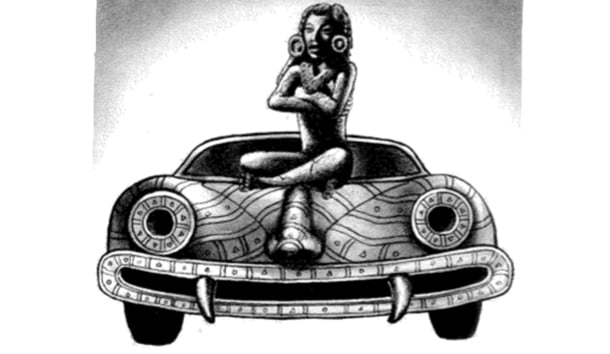

“Revolución es una mierda sexual,” Rosas had said, a cholo, a professional revolutionary, and a professor at the University of Lima. He drove a silver BMW and had two other cars for errands, but to Roberto and me he paid slave wages. “There’ll be more,” he’d tell us, smiling. “Mañana,” I’d say, and he’d laugh merrily.

There was also the bearded Jorge, whose surname began with a “de.” He also asked me what I thought of the Revolution, having come from a Communist country. I had to tell him I thought nothing, never having seen one that was genuine. I was still a socialist then but had already begun to think of the Revolution allegorically. Wanting to impress me, Jorge revealed that he and his movie-director wife watched Cuban movies in the Peruvian Ministry of Labor.

Sitting on the sidewalk, in large areas of downtown Lima, innumerable people sold rotten bananas, old newspapers, used sandals made of old tires, fruit juices from filthy glasses, pieces of barbecued meat, peanuts, mirrors, saints, hats, shoelaces, blankets, souvenirs, books, clothing. I hoped to God someone was buying.

Maybe Marilena is still alive, having had the sense to stop visiting the Indios after the Sendero Luminoso began their killings. The Shining Path guerrillas, inspired by Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge, are prowling the hills of Ayacucho today, using their machetes to lop off the limbs of any Indios who are unwilling to exterminate the gringos.

When B. Traven wrote The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Rebellion of the Hanged, The White Rose, and other books about his adopted Mexico, he was acclaimed as a new Jack London, and a champion of the oppressed. Whether B. Traven was Beriek Traven Torsan, born May 5, 1890, of Scandinavian parents in Chicago, or just an expatriate German, the lure of Latin America was as strong in his time, as in ours, and as deadly. Benjamin Linder succumbed to it like a fallen angel, naive or vain enough to try to exculpate a whole nation. Like many college-educated young Americans, he felt guilty about being fed, washed, and clothed, in the face of Nicaraguan misery. In his novel Underdogs, Mariano Azuela writes of a young intellectual that he “already shared this hidden, implacably mortal hatred of the upper classes, of his officers, and his superiors, felt that a veil had been removed from his eyes; clearly, now he saw the final outcome of the struggle.” The Tenderfoot, as Pancho Villa’s soldiers called him, was not an Indian but was trying his best to become one, and the peasants pitied him.

In the Museum of Fine Arts in Lima, only a single room bore the sign “Pre-Columbian Art.” The rest belonged to the bric-a-brac of Europe, barbarically interpreted by a New World. I passed savage churches in misused stone and saw crowds of people crossing themselves in their murky depths or just passing by. I walked under heavy, carved, wooden balconies, in a city that had no sun, and where the dust covered everything like a plague.

Beside Lima was the ocean. Muddy green, its waves long and rolling, almost hidden by the fog, the ocean whispered with its pebbly beaches, undercutting the dusty cliffs with the city on their edge. From the ocean, gray shadows came and glided between the glass curtain-walls of Old Lima.

Pterodactyls were flying over Lima. Pelicans, dignified, atavistic, and funny. They were sad because there was no more fish, and they were starving. Pesqueros were also sad because there was no fish. They had overfished for years, and ground the anchovies into fish flour, becoming millionaires, one and all. They were wondering, like the pelicans, what was going on.

The sky above the Andes was dark and immobile. From its middle a sun shone—white and sharp and different from the one we know. The mountain was endless, ordered; on its sides eternal snows melted eternally, while the trains crawled along, full of people eating in panic. In the Andes, a man must be religious.

The road to Sillustani was pure Third World: unpaved, treacherous, hard, like a tribute. In unearthly absence a lake existed, searingly blue, surrounded by reeds and water plants which scattered cattle ate, standing halfway in the water.

“In Oregon,” said Campbell, an American biologist to me, “cows don’t graze in water.” Campbell, his Scottish- German-American eyes humorous, was as unlike Benjamin Linder as a man could be, for he had come to Peru to work, and be paid for it. Campbell knew Peru—he was the man who told me of Sillustani—yet, he never talked of the Indios, whose fisheries he was trying to protect. Whereas Linder was young and had started working as a circus artist in Managua, Campbell was middle-aged, and for him the Revolution meant clearing the ancient pre-Incaic irrigation canals on the coast and letting the desert bloom, as it had once before, out of anyone’s memory.

There was a promontory in the lake, and it must have been an island, once. On it, strangely unencompassable the stone chulpas stood, base up, outside time, space, memory, even the imagination. They were old.

“The chulpas are tombs,” said Campbell, knowing more than any man could. The gargantuan truncated cones could have been telephone booths, for all I, or anyone else could argue. The stones were sculpted by someone Henry Moore must have imitated—fairly regular, their joints formed thin, geometric lines, the only such I haven’t seen on paper. Some granite stones were lying around, like Lego blocks. The blocks were 20 feet long, 15 feet wide, 10 feet thick.

There is a past in Peru, as in much of the rest of Latin America. Whoever built Sillustani knew as much as men ever did or possibly will.

There are worlds of different weight, and to know them is to praise God—Garcilaso de la Vega, an Inca, came back after a long stay in Spain still an Indian, while Pizzaro remained forever a Spaniard. Today, Peruvians recognize him in bronze, on Lima’s Plaza de Armas. “Caballero sin caballo,” an old Indian woman laughed after me at the Juliaca fair, paying homage to my origins. Benjamin Linder, on the other hand, was a victim, because he was a gringo. The thousands of Chicanos congregating in Chicago’s Lake Shore Park are not, nor will they ever be: impassive and stolid, they lift weights at the Y and speak little. If their rivers in the Altiplano are carrying detergent foam, they know who’s to blame, for they have been taught well, by the same people as Benjamin Linder. They know they have rights. In the land of the gringos, they search for peace, unwilling to forego anything.

Peoples ebb and flow—the Chicanos’ only obligation may be to reclaim North America that their cousins have let go, in an unforgotten and an unforgiven past. The future, ever so fickle and brief, belongs to those who would grasp it, sinless and guiltless. When the Incas subdued the Mochicas, the Aymara and the Quechuas, or when the Aztecs ripped out the hearts of thousands of victims, history was theirs, regardless of who built the pyramids, the chulpas, Sacsahuaman, or Quenco. Octavio Paz, the blue-eyed European Indian, was not on hand to lament anyone’s fate; Benjamin Linder’s parents had no counterparts. The Indios then probably stood the same as today; somber, sullen, their bare feet caked with mud, their enormous black toenails turned like talons.

Leave a Reply