In 1949, America’s ten most-affluent metropolitan areas, as determined by median household income, were Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Chicago, Dayton, Akron, San Francisco, New York, and Hartford, Connecticut. Washington, D.C., was 15th, trailing Youngstown, Rochester, Buffalo, and Columbus.

This list no doubt strikes many contemporary readers as surreal—even bizarre. How could the rust-belt cities of Detroit and Cleveland ever have been richer than D.C. and New York?

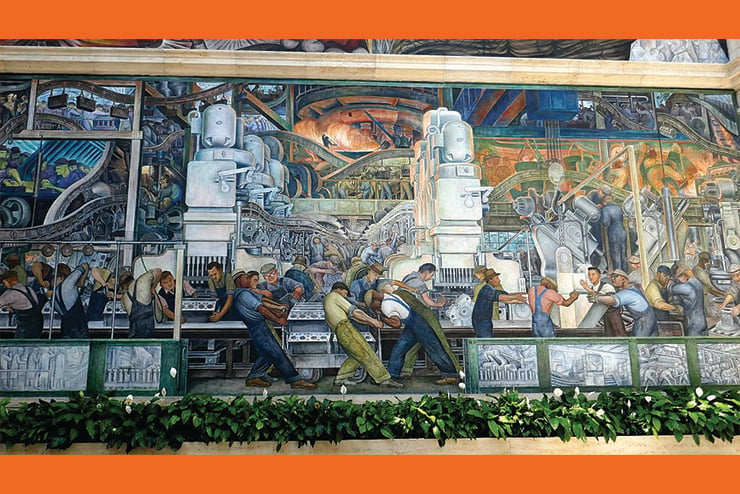

In a word, manufacturing. There are many ways to redistribute wealth—the governmental subsidies of D.C. and the financial shenanigans of New York being but two examples. But there are only a handful of ways to create wealth, the most potent of which is manufacturing. Extracting the silica used to make computer chips creates a certain amount of wealth. Using that silica to manufacture computer chips creates vastly more wealth, and using those computer chips to manufacture the myriad machines and devices that use those chips creates even more wealth.

There are additional benefits to having an economy based on manufacturing. The example of silica chips shows the close connection between manufacturing and innovation. Without silica chips, there would be no Silicon Valley and all the inventions that have come from there.

You may recall President George H. W. Bush’s economic adviser, Michael Boskin, perfectly embodying the stupidity of mainstream thinking on outsourcing and offshoring when he dismissed concerns about America losing its dominance in computer chips by saying that, from an economic standpoint, he saw no difference between potato chips and computer chips. To state the obvious, without potato chips, we’d simply eat different snacks; without computer chips, we would fall several rungs down the technological ladder. Boskin and “the respectable right” were as wrong about this as they’ve ever been about anything.

The list of 1949’s wealthiest cities illustrates another great benefit that flows from an economy based on manufacturing. America had just won World War II, in substantial part because America’s preexisting manufacturing base located in cities ringing the Great Lakes had just drowned Germany and Japan in a mighty torrent of planes, tanks, ships, and guns. The Axis could not match the productivity of our now-denigrated Rust Belt; without it, the Allies may well have lost the war.

Like most things of value, America’s manufacturing base did not come into being overnight. In a sense, America’s manufacturing sector began on July 4, 1789, when Congress passed the Tariff Act of 1789, a stated purpose of which was “the encouragement and protection of manufacturers.” America’s manufacturing thrived behind tariff walls, particularly between 1860 and 1932.

Then we threw it all away. We convinced ourselves that manufacturing was “dirty,” that the future belonged to “knowledge workers,” and any problem caused by imports could be solved by retraining laid-off factory workers to be computer programmers. Corporate leaders made shareholders rich beyond the dreams of avarice to the long-term benefit of no one but our foreign competitors.

Those competitors responded to our attempt to commit economic suicide by trying to murder us first. The Japanese destroyed one American industry after another in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Chinese picked up where the Japanese left off around the turn of this century. The result: we let the industrial Midwest rust.

Jerry Useem discusses all this in an excellent article on Boeing in the April issue of The Atlantic titled “Boeing and the Dark Age of American Manufacturing.”

Useem details how Boeing went from being a company that made one excellent airplane after another to a company that outsourced so much of the production of the flawed and dangerous 737, including to foreign companies, that its executives could not explain to the FAA how the plane was made—because they did not know!

Briefly put, Boeing went from being a company run by engineers who were close to the manufacturing process to finance types who thought factories were icky. Boeing no longer felt any loyalty to its workers or its longtime hometown. It moved its headquarters to Chicago and tried to outsource its way to prosperity.

Fortunately, as with the issue of illegal immigration, the truth about “outsourcing” and “offshoring” is becoming clear to Americans of all demographic backgrounds and political orientations. Donald Trump also understands this, which is why he is calling for a 10-percent across-the-board tariff and tariffs of up to 65 percent against Chinese companies that are trying to eliminate American manufacturers.

The only question I have is, how many American executives are left who can run manufacturing companies the way Boeing was run in its heyday? ◆

Leave a Reply