This summer once again has seen the mainstream media engaged in heat wave hysteria. Instead of “It’s summer folks; expect hot weather,” we get “A ‘heat dome’ is causing temperatures to break records and threaten lives.” A “heat dome”? Years ago, it would have been reported that high pressure had settled on a particular area, causing temperatures to soar. But now, each July, August, and September, we hear hyperbolic descriptions of hot weather as if it’s not something that has occurred every summer in living memory.

I suppose it’s a sign of my age that the worst heat wave I remember occurred not this year, or last, or four years ago—but in 1955. For those of us living in Pacific Palisades, a small town sandwiched between the Santa Monica Mountains on one side and bluffs that drop precipitously down to the beach and the Pacific Ocean on the other, the 1955 heat wave was something to behold. In those days, the Palisades rarely had summer daytime temperatures above 80 degrees. A high of 85 would have been a scorcher. However, in September 1955, we had day after day of nearly 100 or above. Same for our next-door neighbor up the coast, Malibu. Our next-door neighbor down the coast, Santa Monica, averaged closer to 90 degrees each of the heat-wave days, but only because Santa Monica took her official temperatures at the end of the Santa Monica Pier, which juts a couple hundred yards into the ocean. This trick gave Santa Monica the most equable climate in the nation, on paper anyway—and Santa Monica bragged about it.

I remember it all clearly because for a Palisades beach-kid, the temperatures—not for a single day but for more than a week—were shocking, and no one had air conditioning. Typically, our summer days started with fog and overcast and didn’t clear until 10 in the morning. By then, the sea breeze had started to pick up, much to the dismay of those of us surfing, who saw the beautiful early-morning glassy-water surface begin to ripple. That same sea breeze, so hated by surfers, usually kept summer high temperatures in the 70s along the coast.

As bad as the heat wave was for us coastal softies, it was far worse for those in Los Angeles, where temperatures averaged 7-10 degrees hotter. The temperature soared to 101 in Los Angeles on Aug. 31 and then hit 110 the next day. This was a Palm Springs temperature.

As the night of Sept. 1 turned into the morning of Sept. 2, the temperature in Los Angeles was still in the high 80s. It wasn’t until shortly before dawn that it got down to 83, a record high for an overnight low. Two hours after sunrise, the temperature was back in the 90s, and at 12:45 p.m. it peaked at 108. Sept. 3 cooled to a high of 105. It wasn’t until Sept. 8 that the daily high fell below 100. By that time, 946 people had reportedly died from the excessive and prolonged heat. Mortuaries were overwhelmed.

Inland areas continued to swelter for another two or three days. San Bernardino recorded an unofficial high temperature of 116 degrees and an official high of 115.5 on Sept. 6, after several days of 111 and one of 114. In addition to the many people who succumbed to the heat, hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of small livestock, such as chickens and rabbits, also died.

In the midst of the 1955 heat wave, I recall adults talking about the heat wave of July 1936, which affected most of the United States but was particularly severe on the Great Plains and in the upper Midwest. Wisconsin and Minnesota, known for their icebox winters, both had more than one town record official temperatures of 114 degrees. They were easily topped by another icebox state, North Dakota, which saw the town of Steele record a high of 121. Two towns in Iowa hit 117 degrees, and Nebraska and Missouri each had two towns with highs of 118. Oklahoma had two towns with highs of 120 degrees and Kansas had two with 121-degree highs. To this day, the 1936 heat wave, which killed 5,000 to 10,000 Americans, remains the hottest on record; and the hottest single month in U.S. history remains July 1936.

Imagine if we were having temperatures of 121 degrees in those states today. What would our global-warming Chicken Littles with memories that go back less than a decade do? Hysteria may be too gentle a word.

Until fairly recently, Americans stoically endured hot summers. During the heat wave of 1886 on the northern High Plains, the town of Dickinson in Dakota Territory, went ahead with a great Fourth of July celebration despite temperatures hovering around 112 degrees. There was a parade that featured a band, female equestrians, Civil War veterans, two floats—one with a Lady Liberty and one with 38 schoolgirls dressed in white, representing the states of the Union—and dozens of carriages carrying townsfolk. Hundreds of people came into Dickinson from all the surrounding ranches and towns for the celebration. They stood in the blazing sun and watched the parade with such enthusiasm that many jumped in at the back and joined the procession. The featured speaker of the day was a prominent rancher by the name of Theodore Roosevelt, who delivered his first major public speech. He did so dressed in a suit.

The highest temperature ever recorded by an official weather station anywhere in the world is the 134-degree reading taken at Furnace Creek, in Death Valley, on July 10, 1913. Once upon a time, we California kids were taught about Death Valley and its record-setting temperatures. It was one of my home state’s many distinctions that made me a California chauvinist. Death Valley holds another distinction, one that helps explain why it’s so hot: the floor of the valley is generally below sea level, and at Badwater, it’s 282 feet below, making it the lowest spot not only in the U.S. but in all of North America.

A new phrase I’ve been hearing more often from climate alarmists and the mainstream media is “weather extremes.” I suppose this switch from “global warming” has become necessary because of several record-setting low temperatures during recent winters. However, radical annual swings in highs and lows are nothing new. The year of the highest temperature in Death Valley, 1913, also saw the lowest temperature ever recorded in the Valley, 15 degrees at Greenland Ranch on Jan. 2.

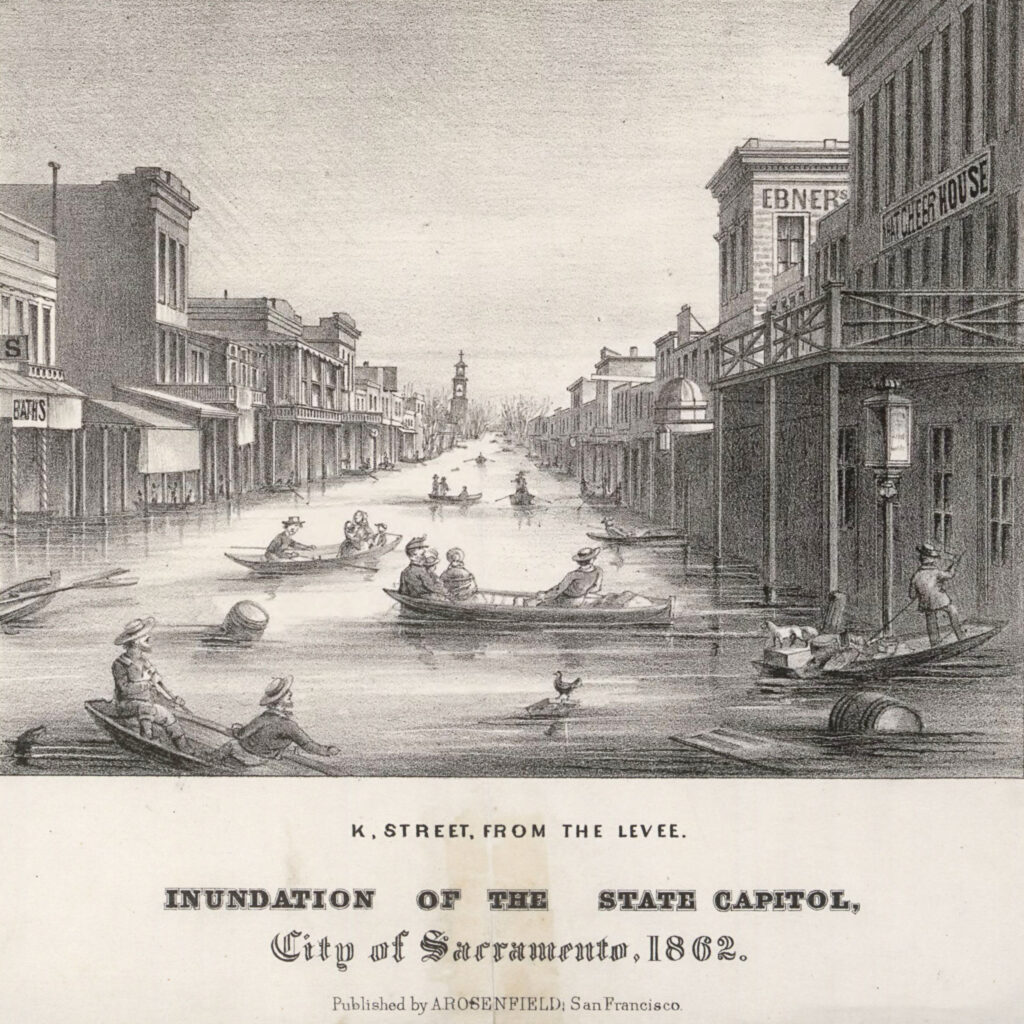

Extreme-weather hysterics are also hyperventilating about heavy rainfalls and severe droughts. Again, this is nothing new. The 1860s in California are a case in point. Heavy rain came to California in November 1861 and continued intermittently until just before Christmas. Then a series of storms brought rain for a month. By then, San Francisco, which normally receives 23 inches for an entire rainfall season, had received 49 inches, and the Sacramento River had reached a flood stage of 24 feet. Mining camps in the foothills of the Sierras received precipitation of biblical proportions: Nevada City, 115 inches; Sonora, 102; Red Dog, over 11 inches in one day; Grass Valley, 9 inches.

The entire Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys were underwater, up to 30 feet deep in places. The state capital, Sacramento, was chest-deep in water and Leland Stanford was forced to go to his gubernatorial inauguration in a rowboat. “Oregon, Washington and California alike,” said the San Francisco Call on Jan. 12, 1862, “have been wrecked … and Sacramento has been drowned out of existence.”

Also drowned out of existence were farms and ranches, which lost more than 200,000 cattle and 600,000 sheep. Estimates put the loss of human life at more than 4,000 people.

A portion of these losses came from Southern California, which also felt the fury of the storms. By the end of January, Los Angeles had received 37 inches of rainfall, nearly triple her annual average. “On Tuesday last,” commented the Los Angeles Star, “the sun made its appearance. The phenomenon lasted several minutes and was witnessed by a great number of persons.”

The next two years saw almost no rain. Areas that had received 50 or 60 inches of rain in one year received no more than 7 or 8 inches in two. Summers saw temperatures soar into the triple digits for days on end. The grasslands that had caused cattle to grow fat disappeared. Upwards of 250,000 cattle died. The combined losses from the flood and the drought destroyed California’s fabled ranchos, some of them dating back to the first Spanish land grants of the 1780s. Destroyed also was the way of life of the rancho dons and their families, depicted so romantically by Richard Henry Dana in his memoir, Two Years Before the Mast.

The most recent term used by the climate alarmists is the all-inclusive “climate change”—as if the climate hasn’t continually been changing for 4 billion years. Heck, millions of years ago we had dinosaurs living in jungles and swamps in Wyoming! Fifteen-thousand years ago, much of North America was covered by sheets of ice that were three miles deep in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Think of the global warming that began some 11,000 years ago and has brought us to today’s climate. What has Man had to do with that? And what will Man have to do with the climate when our current warm period ends and we enter another ice age?

Man can certainly pollute, contaminate, and decimate local environments—but effect significant changes in global climate? No. Man has no control over the principal factors determining climate: tectonic-plate movement, circulation patterns of ocean and air currents, volcanic eruptions, meteorite strikes, the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit, shifts in the tilt of the earth’s axis, the precession of the axis, and activity on the surface of the Sun.

Don’t expect virtue-signaling elitists and hysterical green cultists flying to climate conferences in their private jets to rescue us from our next heat wave. Think instead of those rugged souls in Dakota Territory on the Fourth of July, 1886, who didn’t let a hot day spoil their fun. ◆

Image via pxhere.com, CC0 Public Domain

Leave a Reply