It seems that Benghazi is remembered today only for the 2012 attack on the American diplomatic mission there. In the 1940’s and 50’s, though, it was known for launching the planes that conducted Operation Tidal Wave, a brilliant example of the heroism of American airmen, and an equally brilliant example of Murphy’s Law. The former resulted in the awarding of five Medals of Honor, more than any other air mission in history, and the latter in the loss of one third of the planes that participated.

The mission’s objective was the bombing of nine oil refineries at Ploesti, Rumania, which produced about 35 percent of Axis supplies. There had been a minor air raid on the refineries in 1942, but with the Americans in control of Libya by the summer of 1943, it was thought a propitious time to launch a major strike from airfields at Benghazi. Two Bomb Groups from the Ninth Air Force, the 98th and 376th, and three Bomb Groups from the Eighth Air Force, the 44th, 93rd, and 389th, would do the job. Because of its fuel capacity, the B-24 Liberator would be used. A high-wing, four-engined converted seaplane, the B-24 was not the most stable bomber, and its flight characteristics were dramatically compromised when the plane took hits.

Since the handful of bombers that attacked the refineries in June 1942 encountered only limited antiaircraft fire, it was thought that the attack could be executed by day and at low altitude to improve accuracy and avoid enemy radar. Unknown to American planners, the Germans had fortified the area around Ploesti since the 1942 raid with not only hundreds of antiaircraft guns but three Luftwaffe fighter groups, which included more than 50 Me-109s. A daytime attack also required the element of surprise, which meant the operation must be kept secret. Again, unknown to American planners, German intelligence stations in Greece were monitoring American activities in Libya. Murphy’s Law was in full swing.

At daybreak on August 1, 1943, B-24s, equipped with extra fuel tanks and loaded with bombs, began rolling down several dusty runways and lifting off. One exploded, but 177 took flight and headed north across the Mediterranean. Before an hour was up, ten had developed mechanical problems and turned back. Worst of all, the lead bomber for the mission with the lead navigator suddenly lost altitude and plunged into the sea. The second-in-command bomber descended to look for survivors but found not a soul. With little fuel burned off and still with its bomb load intact, the Liberator struggled to climb and rejoin the formation. Its engines began overheating, and it was forced to turn for home.

The attacking force made a turn at Corfu and headed northeast over the Albanian shoreline. Coast watchers were soon radioing German intelligence officers, who suspected the air armada, now numbering 165, was headed for the Ploesti refineries.

For the flight over the Balkan mountains half of the bombers climbed to 12,000′, and the other half to 16,000′. Those at the higher altitude picked up a strong tailwind. The two groups were quickly separated. The lead plane of the faster group reached what its navigator thought was the final checkpoint and made the turn for Ploesti. They were actually on their way to Bucharest. They later corrected the error but would be approaching Ploesti from the south rather than the west as planned and were hopelessly separated from the slower group, which made the turn at the correct checkpoint. The two groups would hit the targets at right angles to each other and have to maneuver through one another’s flight paths. In the meantime, German antiaircraft guns were ready, and Messerschmitts were scrambling.

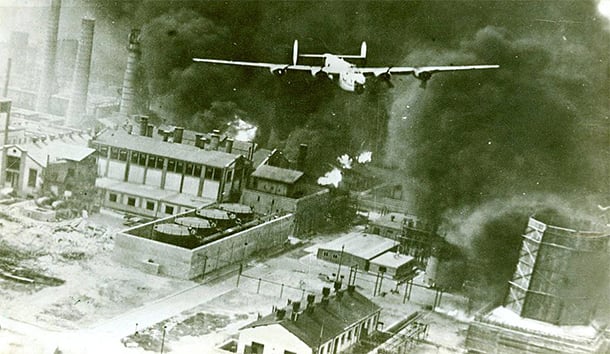

At 200′ above ground level and descending the American bombers began their runs over the refineries. They couldn’t miss, but neither could the antiaircraft fire. The refineries exploded in flames, and B-24s exploded in balls of fire. Crippled planes limped off and crash-landed in fields. Ole Irish, with Lt. Frank McLaughlin at the controls, had one of her engines knocked out, and another was sputtering. Bullet holes were everywhere. McLaughlin asked his crew if they wanted to land in nearby neutral Turkey or attempt the long flight back to Libya on two and a half engines. They opted for the latter, jettisoning everything they could, including their .50 caliber guns, to lighten the load. Waist gunner Don Pierce, now without his machine gun, said they relieved the tension by talking about “that shot of whiskey they’d give us when we got back.” Hours later they landed on the first airstrip in Libya they came to, and just then the sputtering engine quit.

Only 88 bombers made it back to Benghazi, and 55 of those were badly damaged. The losses of airmen were devastating: 310 killed, 108 captured, and 78 interned in Turkey. Lt. Col. Addison Baker, 2nd Lt. Lloyd Hughes, and Maj. John Jerstad were awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously. Col. Leon Johnson and Col. John Kane lived to receive it.

Leave a Reply