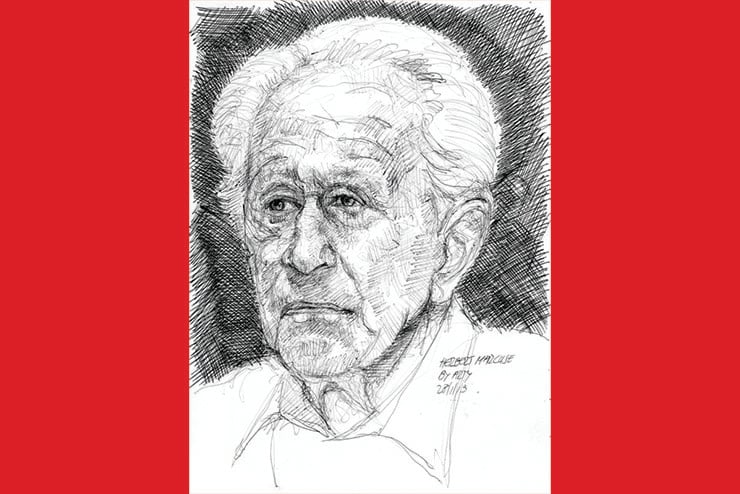

I first became aware of cultural Marxism as an undergraduate student at UCLA during the 1960s. There were several professors and teaching assistants with whom I came into contact who were fans of Herbert Marcuse and his two most recent books, One-Dimensional Man and A Critique of Pure Tolerance. Marcuse had once been an orthodox, revolutionary, class-struggle Marxist but during the post-World War II era had moved towards achieving the same communist goals through transforming the culture—education, art, literature, language, religion, family, even one’s own consciousness.

I recall that one of the teaching assistants—I’ll call him Bill—announced to us lowly undergrads in his section that he was a Marxist. I suppose that was a bold admission to make at the time, but I could see he took delight in projecting himself as a revolutionary. He was our own campus Che, and like Che, he had come from an upper-middle-class family and had attended private schools. Nonetheless, he saw class struggle everywhere and was on a mission to destroy capitalism. While he praised the work of Marcuse, he seemed to have missed Marcuse’s essential message of insidiously changing the culture first. Bill’s approach was to take some of his comrades to the docks in San Pedro to pass out leaflets to longshoremen.

In Bill’s twisted mind, he thought the longshoremen were the perfect proletariat. Of course, he had never met a longshoreman. I don’t know if he had ever even been to San Pedro. The waterfront there was not what it had been during the 1940s and ’50s, but it was still a rugged stretch full of hardened merchant marines, commercial fishermen, and shipyard workers. Bill had long hair—before hippies made it common for guys—and a soft, pudgy body. It was obvious contact sports were foreign to him and the only fight I could ever imagine him in was a verbal duel in a moot court in his prep school. I thought to myself, “This guy will be sliced to bits and used for chum.”

After missing several sections, Bill was back at UCLA looking the worse for wear. Evidently, the longshoremen were not captivated by his leaflets and communist rhetoric. I was only surprised that he hadn’t woken up in the hold of a ship halfway between San Pedro and Singapore—or hadn’t woken up at all.

This is exactly what Marcuse understood—the working classes of Europe, and especially those in America, were not ready for revolutionary change. The longshoremen in San Pedro may have wanted more pay, better working conditions, and more medical benefits, but they did not want a destruction of the American way of life. Marcuse and his fellow cultural Marxists saw the transformation of the culture as the sine qua non of revolutionary change.

Herbert Marcuse was born in 1898 to upper-middle-class Jewish parents in Berlin, Germany. He received an excellent education at primary and secondary schools but upon graduation in 1916 was drafted into the Germany army. He wasn’t sent to the front but spent World War I in Berlin cleaning horse stables. While in the army, he was allowed to attend lectures at the University of Berlin. By that time, he was a confirmed socialist, especially influenced by the works of Karl Marx.

After the war, Marcuse participated in the Spartacist uprising of January 1919, a week-long attempt by socialists and communists to forcibly overthrow the German government. The attempt failed miserably,

which stunned Marcuse, who thought Germany, with its large proletariat class, high unemployment, and food shortages, was ripe for revolution.

Afterwards, Marcuse retreated into academe, first at Humboldt University in Berlin and then at the University of Freiburg, studying literature, philosophy, politics, and economics. He read extensively, including the works of Friedrich Hegel and Sigmund Freud, as well as Martin Heidegger, with whom he studied at Freiburg. In 1933, he went to work for the Institute of Social Research in Frankfurt, which would become known simply as the Frankfurt School. The institute was founded by a Marxist who had a rich inheritance. Because Marcuse was Jewish and conditions in Germany were becoming threatening for Jews, he soon transferred to the Institute’s branch in Geneva, Switzerland.

In 1934, he and several others from the institute immigrated to the United States to work at the institute’s branch at Columbia University in New York City. It was here that members of the institute, in a collaborative effort, began moving from orthodox Marxism to cultural Marxism by developing an interdisciplinary social theory. While still emphasizing the primacy of Marx and economics, they also utilized sociology, philosophy, psychology, linguistics, and history. This approach became known as Critical Theory, which called not only for an end to capitalism but for an entire reordering of society.

Despite Marcuse’s Marxism, the U.S. government put him to work during World War II in the Office of War Information, where he created anti-Nazi propaganda. Later in the war, he worked in the Research and Analysis Branch of the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), as a senior analyst on Germany. After the war, he worked for the State Department as an analyst of Germany and Nazism.

Marcuse left the State Department in 1952 to lecture first at Columbia University and then at Harvard. From 1954 to 1965 he was a professor at Brandeis University and then at the University of California, San Diego, until 1970. He thus spent a decade working for the U.S. government and then nearly 20 years working for universities, both of which he wanted to transform utterly. He took perverse delight in getting paid by the institutions he was working to destroy, and advocated following such a practice to all young leftists.

Marcuse first came to the attention of the wider public with the 1955 publication of Eros and Civilization, his synthesis of Marx and Freud. He argued that sexual instinct and drive should not be repressed and that such repression was an inherent element of Western Civilization. He further argued that capitalism represses the libido of the proletariat. Everything for Marcuse, including sex, was part of an oppression versus liberation paradigm.

Although some have argued Marcuse’s influence on issues such as “gay liberation” has been exaggerated, his well-constructed theoretical challenge to all conventional sexual norms certainly provided intellectual ammunition for gay activist groups and for hippies living in “free love” communes. The sexual aspect of his influence was even seen in the rhetoric of anti-Vietnam War protesters crying, “Make Love Not War.”

It was One-Dimensional Man, though, that made the big splash on campus in my time and was something of a bible for the New Left of the mid-1960s. Within a few years of its publication in 1964, it had sold more than 100,000 copies and had become a staple in college bookstores and on course syllabi. The book argued that modern industrial society had become thoroughly repressive in the West—and also to a lesser degree in the Soviet Union—because it had created a one-dimensional template of thought and action by creating false needs and then delivering the goods to satisfy those needs. This was a kind of consumerism and repression that stifled critical thinking and the revolutionary spirit.

Only a year after One-Dimensional Man was published, A Critique of Pure Tolerance hit the bookshelves. The latter consists of three essays by three authors, including “Repressive Tolerance” by Marcuse. It was Marcuse’s essay that got the most attention and foreshadowed what is now occurring on college campuses and to a lesser degree in America in general. Marcuse argued that to become a truly liberated society and to realize the objective of tolerance we must be “intolerant toward prevailing policies, attitudes, [and] opinions” but tolerant to dissident, subversive, and revolutionary policies, attitudes, and opinions. This exactly describes the conditions on campuses today and what is described as “cancel culture” in society at large.

By 1967—the year of San Francisco’s Summer of Love—Herbert Marcuse had become the New Left’s most important thinker. Chants of “Marx, Mao, and Marcuse” were heard wherever protesters gathered. “I can’t exaggerate how important it was for those of us who knew him, heard him, and read him to have someone of his age and stature legitimizing us and showing solidarity with us,” said Ronald Aronson, a student who worked under Marcuse at Brandeis.

Marcuse inspired dozens of students like Aronson to become professors, high school teachers, or leftist activists in other capacities. Probably the most prominent was Angela Davis, who said, “Herbert Marcuse taught me that it was possible to be an academic, an activist, a scholar, and a revolutionary.” After earning a master’s degree under Marcuse at UC San Diego, Davis was hired in 1969 as an assistant professor of philosophy at UCLA. She didn’t have a Ph.D., a book published, or any real teaching experience but she was black, a woman, a member of the Communist Party, and a student of Marcuse.

Some of Marcuse’s colleagues in the Frankfurt School had problems with Marcuse’s role as the guru of the New Left. Theodor Adorno and others thought his celebrity status had cheapened and compromised the objectives of cultural Marxism.

Less surprising were condemnations of Marcuse from conservative sources. The pope not only condemned Marcuse’s philosophy but condemned Marcuse (and Freud) by name—a rare distinction. California governor Ronald Reagan called for Marcuse’s expulsion from UC San Diego. A group of San Diego conservatives hanged him in effigy from a flagpole at city hall. He received hate mail and death threats. Marcuse was paying a price for his celebrity status and his own “repressive tolerance” was being used against him. He retired from the university in 1970 and died in 1979.

Marcuse’s significant contributions to cultural Marxism and Critical Theory live on. If he were around today, I wonder what he would think of the way his work has been applied to race. Western Civilization, a product of the white man, is now oppressive. Therefore, the white man has to go—or, if he is not eradicated, he must at least be discriminated against, which would be in keeping with repressive tolerance.

If this weren’t all too real and serious, I would find it hilarious, at least from my personal perspective. According to Critical Theory, we white folk are supposed to have something called “white privilege.” In my personal experience, I’ve seen special privileges granted to people because they were not white, but I’ve never received special consideration because I am white. I’m now in my late 70s and I’m still waiting for my white privilege to kick in. ◆

Leave a Reply