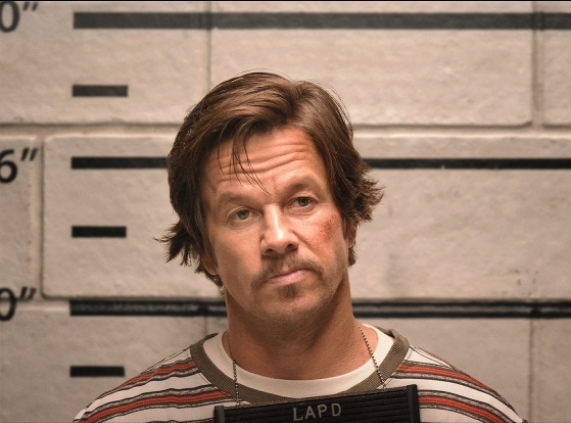

Father Stu

Directed by Rosalind Ross ◆ Written by Rosalind Ross ◆ Produced by Mark Wahlberg (through Columbia Pictures) ◆ Distributed by Sony Pictures

Moonfall

Directed by Roland Emmerich ◆ Written by Roland Emmerich◆ Produced by Roland Emmerich ◆ Distributed by Lionsgate

The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent

Directed by Tom Gormican ◆ Written by Tom Gormican and Kevin Etten ◆ Produced by Nicolas Cage (through Saturn Films) ◆ Distributed by Lionsgate

The first thing to say about Mark Wahlberg’s Father Stu is that the film is not reviewable. Its content is obviously heartfelt, but its construction and acting are hopelessly shoddy. In other words, I feel uncomfortable knocking the film in light of Wahlberg’s genuine commitment to it.

As I watched in the theater, I felt increasingly embarrassed for Wahlberg, who paid to make it from his own funds. I’ve since looked into its subject, Father Stuart Long, and found that Wahlberg’s portrayal of him is not as off the mark as I had supposed. Long seems to have been Augustinian in his theology and Dantesque in his life journey. He was just as self-obsessed and thuggish in his behavior as Wahlberg makes him out to be.

Viewed in a more positive light, Long was the kind of priest I’ve met several times over the course of my life: a dedicated man who wanted to connect with people on a human level and who tried to do so by behaving in a just-folks, rough-and-tumble manner. This strategy seems to have garnered favor from his parishioners in Helena, Montana. He was, as the saying goes, a diamond in the rough, and many of his flock apparently enjoyed his straight-from-the-hip manner.

Speaking as a Catholic, I have to say that Long would not have been my kind of priest. Bluff, tough, and given to profanity, he would have caused me to shrink from his overeager camaraderie. When I’ve encountered this kind of behavior in a priest, I’ve always suspected it was an act developed to gain approval from a cornered audience. So I’ll admit that my displeasure with the man (and therefore his depiction in the film) may reflect my own limitations. Nevertheless, Wahlberg’s presentation of Stu as a man of roughneck ways is more than a little off-putting, especially when it comes to his treatment of Carmen, the woman who first influences him to convert to Catholicism from what he himself believes was his unconsidered atheism.

Through scenes that establish his working-class bona-fides, we first meet Stu as a boxer in Helena, Montana. It’s a sport in which he gained minor distinction, becoming Montana’s Golden Gloves heavyweight champion, but from what I could see, he was far from a leading contender.

When he cannot parlay his amateur success into a professional boxing career, Stu decides to move to Los Angeles, where he’s sure he’ll succeed as an actor. When studios reject him repeatedly, he decides he needs more exposure, so he gets a job as a counter man in a local supermarket’s butcher section. He’s certain that in this position he’ll eventually meet and win over fans. As you can see, there’s a delusional pattern to his efforts. He was profoundly self-centered. Since Walhberg strives to put Long in the most favorable light possible, I was surprised that he would emphasize these unimpressive moments.

A few scenes later, Stu meets Carmen, a pretty young Mexican woman whom he pursues ardently. This, despite her repeated rejections and insistence that she isn’t available for romance—much less for the premarital sex he clearly desires. She only relents after Stu has a serious motorcycle accident that cripples him. The doctor tending to him tells him there’s more to his physical ailments than breaks and scrapes. He had developed a rare disease called inclusion body myositis, which progressively wastes muscles and dramatically reduces life span.

Out of sympathy for Stu, Carmen gets into his hospital bed one bright afternoon. Stu, however, decides that marrying Carmen, who has come to love him, will not help either her or him. Soon after this, he reveals that he intends to become a priest, causing Carmen considerable grief, which she expresses by striking him repeatedly. And, I feel, justifiably. In fact, I had to refrain from applauding her.

The rest of the film follows Father Long’s progressive decline. Walhberg is made to look increasingly bloated and immobilized. But rather than feeling sorry for himself, he decides his suffering is a gift that is bringing him closer to Christ’s suffering. Well, that’s noble—but I couldn’t help wondering if it was just another aspect of his solipsistic self-importance.

We last see Stu entering a hospice facility on his way to death. Afterwards, everyone he knew testifies that he was one hell of a guy. For my money, the film proves that a story may be entirely true but nevertheless feel as phony as a $3 bill.

Roland Emmerich’s space disaster film, Moonfall, doesn’t even pretend to be authentic. The first sign of its inauthenticity is that it miscasts the model-turned-actress Halle Berry as a genius NASA astronomer specializing in the moon. When the orbit of Earth’s satellite gets too close to terra firma (it looks to be no more than a half mile away in the film), it causes disasters, floods, earthquakes, and general panic. You know Berry is in serious mode because she’s sans makeup and has clapped a baseball cap on her head. Her character recruits a master space-shuttle pilot, played by Patrick Wilson, with whom she’s had an ongoing personal drama for years.

Brave souls both, they blast off to thwart the moon’s misbehavior. But there’s an uninvited third astronaut, KC, aboard. He’s a kook whose “research” has led him to conclude that we earthlings have misunderstood the moon since we first looked up at it for romantic inspiration and lovely song refrains. He’s convinced the moon has a mind of its own and, after several billion years, has decided to punish earthlings for their presumptive ways.

Bradley’s conjecture is only half right. What he mistakes for the satellite’s sentience is actually alien life that is using the moon to attack us. The aliens look like huge snake formations comprised of menacing smoke.

From here, the race is on. There’s much bickering over whose analysis is correct, which comes to a full stop when these creatures decide to visit earth and wreak havoc on its less adventurous inhabitants.

All of this is merely the setting for Berry and Wilson to lock lips as their characters resolve their sexual tensions while pulling their shuttle through unimaginable dangers from which the two of them will return home, largely unscathed. The shirking of reality in this romantic flight of fancy is bound to unnerve any audience foolish enough to watch the damn thing. Beautiful actors are simply not enough to sustain such a flimsy film.

And now we come to what can only be called a Nicolas Cage vanity project, The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent. Just a hint to the filmmakers here. Their use of the word “unbearable” in their title was a risky proposition. This film is just that: unbearable. Its purpose is to toy with Cage and his eccentric career, in which he has worked far too much and far too indiscriminately.

Cage, as every moviegoer knows, is a strange fellow, but here he’s not strange enough to carry this self-centered film. The writers and director would have done much better had they chosen as their subject the fully bizarre Christopher Walken, with his uniquely weird line deliveries and unblinking, hallucinatory stare.

In the beginning, we watch Cage moping about his career and throwing tantrums about a film project that some hotshots have been maliciously dangling in front of him while refusing to make a final decision about hiring him or not. His most ardent fan and a man of inexplicable wealth, played by Pedro Pascal, decides he must have Cage star in the film he intends to make. When he offers Cage a million dollars to work with him, Unbearable’s ridiculous shaggy-dog story really gets rolling.

How, one wonders, did the filmmakers think this would go well? And yet, improbably enough, it seems to be doing just that. It has received good reviews, and patrons have lined up to spend their hard-earned money on sheer Hollywood eccentricity. Unbearable has the aura of an Orson Welles extravagance such as The Lady from Shanghai, or of John Huston’s Beat the Devil, both projects that seem to be largely unfinished showcasings of their directors’ whimsy—and perhaps contempt for their audiences.

Lady has Rita Hayworth cavorting with crooks through San Francisco’s Chinatown without discernible purpose, and ends up in a hall of mirrors with the other characters shooting at one another among shards of splintering glass. Huston tried something similar in Beat the Devil, a story that deliberately has no discernible point. Such solipsistic directorial vanity projects are not that uncommon in the history of film. Alain Resnais’s beautiful but purposeless 1961 film, Last Year at Marienbad, begins and ends with a cast of beautiful people wandering interminably among the hedges and shrubs of a perfectly manicured estate. Why? We never learn.

But purposelessness is not a narrative asset. In Unbearable, Cage flounders helplessly in a constant sweat. His voice caterwauls across the Mallorcan hotel setting. Too bad for Nick. Next time, why not try to hook up with your uncle Francis Ford Coppola? He can be weird, too, but he stops short of self-destructive nihilism.

Top image: Pedro Pascal and Nicolas Cage in The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent (Lionsgate)

Leave a Reply