Emily the Criminal

Directed and written by John Patton Ford ◆

Produced by Low Spark Films ◆ Distributed by Roadside Attractions

Don’t Worry Darling

Directed by Olivia Wilde ◆ Written by Katie

Silberman ◆ Produced by New Line Cinema ◆

Distributed by Warner Bros.

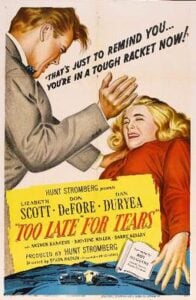

Too Late for Tears (1949)

Directed by Byron Haskin ◆ Written by Roy

Huggins ◆ Produced by Hunt Stromberg ◆

Distributed by United Artists

I didn’t realize it at first, but Emily the Criminal is the movie I had been waiting for. Without special effects, without splashy violence, and with the merest allusion to discreet sexuality, this film creates a searing portrait of working-class rancor in America today, thanks to a fierce performance by Aubrey Plaza and an angry noir script.

The premise is this: Plaza’s Emily, is a talented artist weighed down with $70,000 in debt, courtesy of the student loans she was encouraged to take out in order to pay tuition at a high-end university art program. She’s trying to pay back the loan but falling seriously behind in her installments. Her minimum-wage job at a food-service company doesn’t provide an adequate salary.

She needs a higher-paying job, so when we first meet her, she’s being interviewed by a personnel functionary at a corporation. This gentleman is in the process of turning her down. To do so, he’s reading from a file that includes details of Emily’s work and personal history. Emily rises angrily and asks him if he’s already decided against hiring her. He explains that since she’s a convicted felon, he can’t hire her; he points out that he’s merely doing his job. We don’t learn at first why Emily was convicted, but when we do, we can sympathize with the bureaucrat: she assaulted her boyfriend violently enough to put him in the hospital.

At this point, the film’s narrative takes off. Mostly unemployable, Emily is desperate enough to turn to crime, which she soon does by joining a credit-card scamming operation. Having already been taken advantage of by the financial industry herself, she’s not reluctant to turn some financial abuse on others. Under the tutelage of a low-level criminal, she becomes a dummy customer using phony credit cards to steal merchandise, which she then fences to others at below market cost, sharing her ill-gotten proceeds with her criminal mentor.

Things seem to go well at first, but when her mentor recognizes Emily has a talent for scamming, he promotes her to a higher-stakes operation, putting the tyro scammer in the crosshairs of some genuinely dangerous people, including ruthless thieves running an international car-theft operation. Unlike in the low-stakes department-store scams she’s been doing, in this enterprise, she finds herself risking her life. Being a formidable woman, she arms herself with a taser and carpet razor, both of which she uses on some low-level predators who try to rob her at home. Of course, she winds up behind bars until her mentor sends an unprincipled lawyer to spring her.

When she and her partner in crime decide to rob the operation’s higher ups, their attempt ends catastrophically. Emily has no choice but to light out to new territory, where she begins supporting herself by applying everything she’s learned to start her own criminal theft operation.

The film’s plot skillfully focuses on a real underclass predicament. Emily is cornered by what seems to be America’s promise but often turns out to be a lure drawing the unwary into deeper trouble than they could have imagined. I know quite a few people who have become ensnared by debts they’ve undertaken in order to advance their prospects, only to find their futures undermined by the financial burden they didn’t fully understand. Of course, we can blame such folk for being foolish, but that assessment ignores how they’ve been manipulated by the promises of higher education, by banks offering low-interest loans, and by a society that promotes these steps as the normal and necessary means to future success.

Consider the ruinous rise in college tuitions over the past 20 years. By some measures, the private institution’s costs have gone up about 125 percent. These schools have been taking full advantage of a public led to believe their progeny will fail to achieve their potential unless they’re supported by a costly degree. And the schools are abetted by banks ever ready to lend to a desperate pool of respectable citizens, fearful that they will fail their children if they don’t go along with this lunacy.

These are the circumstances that have engendered Emily’s predicament and sent her willy-nilly into increasingly desperate measures. The film’s conclusion is not reassuring. Like most satire, it leaves its predicament unresolved, implicitly beckoning us to take matters into our own hands.

This is an important and timely film, especially so with our current president prattling about forgiving student loan debts with money pilfered from taxpaying Americans, college graduates or not.

in Don’t Worry Darling

(New Line Cinema)

Another film, Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling, is one of those that’s good enough to make you wish it were better. At first, it seemed a retread of The Stepford Wives, an allegory of those familiar middle-class blues. The film gets underway by first displaying the middle-class homes you would expect in those notorious 1950s. Everything’s pristine, fairly glowing with fashionability, and designed to accommodate the upward striving of the young couples living within them.

We’re not surprised when presented with the breakfast scene of one couple, Alice (Florence Pugh) and Jack (Harry Styles), in which everything is robotically orchestrated but balanced uncertainly over an atmosphere of unacknowledged angst. They live in a town named Victory, where families are supported by a company named Victory Enterprises, about which the husbands never willingly talk.

When the company boss, Frank, gives a speech, he’s all bonhomie and cooperative pep, and appeals to their desire for unity in the effort to keep Victory, both the company and town, succeeding. Frank’s speech is a parody of the kind of corporate ethos that bosses used to foster among their underlings. In this case, the ethos calls for wives to give up their memories and attainments in order to serve their husbands and communities. Alice had been a highly regarded university research scientist. This is a feminist film, so it’s necessary to present its male characters as preening bullies laying down the rules their women are expected to obey. Presumably, the men have deprived their women of public distinction lest it threaten male self-esteem.

When Alice makes her way to the company headquarters, she discovers the truth: they’re living in a simulated world. One of the wives explains to Alice that she knew it all along but that she had had two children before and wanted to have them back even if only as simulations in this technologically crafted world.

The film has its problems. It is a feminist fantasy par excellence, yet on a second viewing, I still found it dramatically and thematically satisfying.

There is no shortage of feminist films on offer in post-#MeToo Hollywood, and recent American films often don’t dare to feature women as true villains—Emily the Criminal being a rare exception—unless of course their crimes are committed on behalf of a noble and explicitly feminist agenda. One of the best examples of this film of female anti-hero villains was Ridley Scott’s 1991 film, Thelma & Louise.

film Too Late for Tears

(United Artists)

Nevertheless, older Hollywood gave us many notable films depicting crime committed by ladies with no loftier purpose than self-enrichment. In White Heat, (1949), Margaret Wycherly gave an unforgettable performance as a viciously criminal mom. Another film, Too Late for Tears (1949), presented Lizabeth Scott with a similar opportunity. This is far from a good film. Its plot is ridiculous, its acting unconvincing. Even the suits the male actors wear seem to have come from the lowest bargain basements. Yet it must speak to some critical desire, for critics have unaccountably given it a high rating on the Rotten Tomatoes website.

Scott plays Jane Palmer, a lower middle-class woman disappointed by her material circumstances. She’s sure her quantum has not reached her deserved wantum. Then fate steps in. As she and her husband are driving to what promises to be a swank party, another car races by, and its occupant tosses a bag of money totaling $60,000 into their back seat. Gazing at its contents, Jane’s eyes widen, and a satisfied smile lights up her usually pouting puss.

Her law-abiding husband, Alan (Arthur Kennedy), recognizes the danger the cash poses and wants to turn the money over to the police. Jane, however, persuades him to keep the money just for a while, promising she will not spend any of it. Believing her, Alan weakly accedes to her wish. Jane then goes on a delirious spending spree, buying furs and high-fashion dresses.

And then the predictable worst occurs when the gangster (played by a snarling Dan Duryea) who threw the money into the Palmer’s car shows up to get it. From this point on, the plot is comprised of mayhem, scheming, and murder as it moves to its inevitable conclusion, with but one surprise—quite an unconvincing whopper.

As the lady villain, Scott is alluring. In repose, her face is beautiful, but as she goes through her noir paces, it becomes a scowling visage of villainous intent. As such, her femme fatale performance is the one memorable feature in the film. Scott displays some genuine acting ability by convincingly playing a woman with whom no sane man, woman, nor beast would ever want to tangle.

Leave a Reply