It is a small town in Bavaria, and it is at least 32 degrees C. The camera weighs heavy in my hands, and I can feel speckles of sweat accumulating beneath my black rucksack, as it soaks up the sun like a square and sinister sponge. All around us are people similarly suffering, but good-tempered withal—a Sol-worshiping Mare Germanicum of blonds and blondes as far as we can see in all directions. They, too, have cameras (and speckles of sweat), and they, too, are looking along the road in the same direction. As the vehicle comes around the corner beside the Elefanten-Apotheke, dozens of fingers depress camera buttons, and an admiring “Ooh!” can be heard from the finger-chewing children.

There is a large horse pulling the heavy covered cart, a hairy-hoofed behemoth like an English shire horse, or the steed of the famous Bamberger Reiter. It is not this magnificent beast that has elicited the response, however, but its yokemate, a massive ox, its cable-like muscles surging beneath its supple and shiny skin, as he and his equine assistant take the strain of all that wood, together with the weight of the four men who sit inside, clad in the most festive fashions of the first half of the 17th century. “It is the Prince of Denmark!” a black-clad woman announces excitedly through a microphone, to the enthusiastic applause and excited chatter of engrossed Bayerische families.

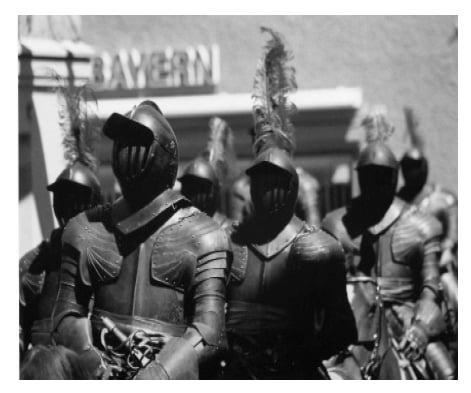

And then the characteristic noise of the parade bursts out again, as yet more pike-hefting mercenaries pass along the road, to the hackle-raising, foot-tapping accompaniment of massed fifes and drums (and occasional bagpipes). We have been hearing this noise all weekend, interspersed with musket- and cannonfire, as some 5,000 reenactors crowd into Memmingen for the quadrennial evocation of the summer of 1630, when all of Europe was drowning in denominational ichor, and the great Habsburg general Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein was uneasily encamped outside the town.

Here comes the man himself—in plain, black armor, his visor down, riding with his sable escort, their lances fluttering with pennons. It must be uncomfortable in that armor today, as it must have been uncomfortable to have been in the real Wallenstein’s skin during those dreadful Thirty Years in which around one third of all Germans (estimates vary wildly) were slaughtered and Wallenstein’s fortunes ebbed and flowed according to the vagaries of Emperor Ferdinand’s Holy Roman temperament.

Wallenstein (with his great fellow general, Tilly) had proved his worth to the Catholic cause time and again as Bavarians, Prussians, Mecklenburgers, Holsteiners, Austrians, Moravians, Danes, Swedes, Spaniards, French, and Poles—and their proxies—all surged repetitiously and confusingly north and south through Europe, at such battles as Lübeck (1629), after which the Danes had sued for peace. But in the summer of 1630, Wallenstein was about to be dismissed under suspicion of disloyalty, and the Swedish Protestant vanguard was ranging southward as the Catholic forces fell back in disarray deep into Habsburg territory. The people of Memmingen—which had been a Protestant town since 1522—must have wondered what Wallenstein was planning and worried what his army might do to an heretical town in the center of a continent in chaos.

In the event, Wallenstein simply went away again, following his martial star back northward. He was recalled to the Catholic colors in 1631 after the death of Tilly, but the following year was defeated by the Swedes at Lützen (although their king, Gustavus Adolphus, died in the battle). As if this were not bad enough, he was now under suspicion again of plotting with the Protestants and seeking to usurp the Habsburg throne. His enemies highlighted the fact that Wallenstein had been born Protestant (although he had converted in his 20’s), his wealth and influence (even Ferdinand owed him money), his modest Bohemian lower-nobility roots, and his possession of a large private army as reasons why the emperor should not trust him. Their slanders (or well-founded insinuations) operated all too successfully on Ferdinand, and in 1634 Wallenstein was charged with high treason. He lost the support of his soldiers and fled to find sanctuary with the Swedes. At Eger (now Cheb, in what is now the Czech Republic), dragoons under the command of Scottish and Irish officers killed Wallenstein’s few remaining followers while they were dining. A few hours later, an English captain named Walter Devereux broke into Wallenstein’s bedroom in the middle of the night and ran his sword through the unarmed, entreating general. It was a sad and shabby reward for sterling service, even seen against the backdrop of those decades.

But the history that must have been so vile at first hand has transmuted into a joyous pageant, when seen at a distance of almost 380 years in time and from aeons away in degrees of religious commitment. The memory of the Thirty Years War is now an excuse for respectable Germans to doff their Hugo Boss suits and don handmade 17th-century-style garments in a bewildering range of styles and tastefully muted colors.

So back in 1630, here they come again, role-playing reactionaries all, along toward the 15th-century Rat-haus, fifes and drums going again—the tramping and profane ghosts of 400 years ago realized in the persons of sweating Swabian accountants, wilting West-phalian bank managers, and melting Mem-minger mechanics.

Here, mingling with the flamboyant princelings and somber tacticians, are modern men and women with mortgages and cradle-to-grave healthcare, in the guise of lancers, uhlans, halberdiers, bombardiers, fusiliers, musketeers, arquesbusiers, crossbowmen, pikemen, farriers, gunsmiths, cooks, sutlers, tinkers, falconers, acrobats, dancers, contortionists, jugglers, tumblers, troubadours, clergymen, dwarfs, wives, and children—followed by the wounded, by lepers, beggars, deserters, drunks, thieves, and “field mattresses.” Some 60 Englishmen from the civil-war-reenacting Sealed Knot Society are also in Memmingen today. (Later that day, I would overhear one luxuriantly whiskered man who looked eminently Germanic saying to someone in a homely Cockney accent, “Sorry, I don’t spreche the German.” Such exchanges must also have taken place in 1630, when High Germany was the stomping ground for all of Europe’s ardent spirits and many of her reprobates.) There are even—an exotic but probably authentic touch—a few “Hungarian” hussars, as if just arrived from the Great Plain, wearing fur hats or exotic, almost Oriental-looking armor, riding small but tough horses, blowing horns as they come, wielding falcons on their wrists.

The troopers bear a forest of vanished vaunting vexillography, the shadowy chivalry of eclipsed or extinct families—crosses and chalices, crowns, stars, trees, swords, shields, fantastic animals, and of course the Wittelsbach blue-and-white. This is much more than a fancy-dress party; those in the procession all look wonderfully at home, congruous and dignified, as if merely putting on the clothes and coming together has turned them into different people. They walk as if they know they belong somewhere in space and time—participants in a völkisch festival so uncommercialized that you cannot even buy postcards of the parades. Their comfortableness is a reminder of how close they are, not to that period, but to the people of that period. The expressive faces in the long files, whether burly cannon loaders or pretty dancers, could have been copied from medieval German paintings by such Bavarian masters as Dürer or Altdorfer. There is a fitness and familiarity about their physiognomies that blurs the barriers between then and now. Men who look like that 20-stone gunner in his black buckled hat and striped hose are probably now serving with NATO in Afghanistan, maybe hefting shells to bombard the mujahideen just as an Hungarian army including a young captain called Wallenstein once saluted oncoming Ottomans with cannonades.

Before and after the parades, there are craft demonstrations—hatters, printers, paper makers, coppersmiths, silversmiths, gunmakers, tanners, cobblers, candle makers—and, below the surviving medieval fortifications, sprawling tented encampments which only appropriately attired people are allowed to enter, on pain of being ducked in a waiting water butt. These encampments are lit only by firelight and lanterns and heated only by fires, and laughing children are being tossed in blankets or climbing trees in bare feet, while their parents laugh and carouse around the hearth and play guitars and flutes, singing such 17th-century standards as “Wenn die Landsknechts trinken” (“When the Mercenaries Drink”) or “Das Leben ist ein Würfelspiel” (“Life Is a Game of Dice”), or watch puppet-theater performances of folk tales that long predate even the lost summer of 1630.

All around the edge of the encampments are heaving beer tents and wurst stalls, selling Fleisch of questionable but tantalizing taxonomy. Every evening, there are events—the Lagerspiele, or camp entertainments, a mélange of dulcimers and dancing, hurdy-gurdys and human pyramids and fixedly smiling gymnasts whose spinal columns can describe S-shapes. Arguably even better are the Reiterspiele, or riding demonstrations—with quintain tilting, jousting, picking things up from the ground in mid-gallop, wooden pig-sticking and bareback riding at top speed, while fighting off “opponents” or leaping across a trench of fire.

The town is suffused with the seductive smells of cooking meat and woodsmoke, and the sweet tang of horse dung, while pipers and drummers march and countermarch constantly through town, the drumming shaking the windows, the fifes shrilling thrillingly. Singing and shouting goes on till the small hours, when the last few cheery drunks subside, only to start early again the next day, while last night’s heroes snore heavily on open-air palliasses as horses walk gingerly around their heads. But no one minds the noise or the hangovers, because it is safe and never rowdy, because it is only for a week every four years, and, besides, everyone here is part of an inchoate conspiracy of consanguinity and culture.

When the Wallensteinfest ends, Memmingen is suddenly sad and dull. Through some black antimagic, the oxcarts have turned into Skodas, the pikemen have reverted to being builders or traffic wardens, and the tented encampment where we drank beer while we drank in the atmosphere is revealed as wholly false, with the modern lights stripped of their kindly Hessian disguises, and just pale circles to show where tents of roisterers once stood, and charred circles to show the sites of their hearths. It is once again just a quadrangle of municipal park, with flower beds of annuals running rapidly to seed.

The townspeople seem half relieved and half sorry to be given back the town they loaned, heaving a sigh as they roll up the shutters of their shops, while all the shimmering roads toward the prosaic north are chock-a-block with trailer-hauling BMWs driven by Franzs or Lieselottes, and populated by children once again more concerned with PlayStations than with pikes. It’s back to the offices, the schools, the credit-card bills, and the mass-produced furniture, the PVC-framed windows and the television—but also to baths and beds, pensions and good food, in immaculate suburbs where it doesn’t matter too much if your neighbor is a Catholic or a Lutheran.

It has been a very enjoyable game, but much more than a game: It has been an affirmation of Bavaria’s zealously preserved personality, and a salute to fine people of different denominations who stood and died 400 years ago for reasons we can scarcely now recall.

Leave a Reply