Shakespeare contains the cultural history of America. From first to last, Shakespeare is the graph of evolving American values. He early made the transatlantic crossing: It is thought that Cotton Mather was the first in America to acquire a First Folio. Richard III was performed in New York in 1750, and in 1752 the governor entertained the emperor and empress of the Cherokee nation at a performance of Othello in Williamsburg, Virginia. The American revolutionaries seized on Julius Caesar as a parable of tyrannicide, with Brutus as the hero of liberty. Shakespeare was always an honored presence, and became absorbed into the growing pains of the young nation.

The archetypal tourist was Washington Irving, whose charming sketches of visits to Eastcheap and Stratford-upon-Avon are still highly readable. He thought he had seen Shakespeare’s dust, in a vault that laborers had dug adjoining Shakespeare’s. But soon this kind of deferential tourism ran into the growing calls for cultural independence. Whitman thought that “The comedies are altogether unacceptable to America and Democracy.” These calls for an end to the cultural cringe marked a genuine American Renaissance.

American writers took the challenge to Shakespeare much further. It is no accident (as Marxists used to say, and probably still do) that the land of bardolatry gave birth to serious anti-Stratfordism. The first great heretic was Delia Bacon, a monomaniac who, seduced by the accident of her surname, strove to prove that the works of Shakespeare were written by Francis Bacon. To this heresy Mark Twain and Henry James subscribed, with partial support from Nathaniel Hawthorne. The same parricidal urge, linked with a nostalgic desire for aristocratic kinship, continued as Oxfordism into the 20th century—overcoming the objection that the Earl of Oxford died in 1604, 12 years before Shakespeare’s death.

Anti-Stratfordism yielded to, and was marginalized by, the immense pressures to create a Shakespeare of anterior superiority. Wealthy individuals (Huntington, Folger) acquired the sacred texts for their libraries. These texts—quartos and folios—became an asset class like impressionist paintings. Across America, Shakespeare was staged with persistent success. The all-embracing doctrine was “He is ours as he is yours, by common inheritance.”

The distinctive features of Shakespearean institutions in the United States are the resources of the major libraries and the range of theater festivals. The East Coast has the Folger Shakespeare Library, and the West Coast has the Huntington Library; theater festivals with Shakespeare at the masthead are everywhere. The map suggests an emblem of the American scene, the strongholds of scholarship flanking the lights of the theaters. These institutions have great and diverse strengths. The Folger, in Washington, D.C., is the finest Shakespeare library in the world. It holds 82 copies of the First Folio (1623), of the 235 known to exist. The Huntington, in San Marino, California, owns all but three of Shakespeare’s single-text quartos (which, being paperback and relatively cheap, tended to be read out of existence). Only the British Library can match the Huntington’s double of the Good and Bad Quartos of Hamlet.

There were subtler assessments of the alignment between Shakespeare and American culture. Charles William Wallace, in 1914, noted that Shakespeare’s cosmopolitanism and universality of appeal are seen as the process of amalgamation of a heterogenous population. Shakespeare, like the English language, was a great unifying agent. He emerges from the past as proto-American and common ancestor. George Washington, a frequent theater-goer who may have seen all of the available Shakespeare on stage, set the tone. Lincoln read Shakespeare aloud as he was sailing up the Potomac days before his death, and chose Macbeth to recite—the very play in which, by macabre coincidence, Shakespeare may have invented the word assassination. Of the late Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia, it is recorded that in 1994 alone he quoted every Shakespeare play at least once on the Senate floor. Ashley Thorndike’s claim (1927) was perfectly valid for its time: “You can’t be President of the United States unless you have read Shakespeare.”

The culmination of the American Shakespeare came in 1976, when the First World Shakespeare Congress was held in Washington, D.C. The Canadians had actually staged a World Shakespeare Congress in 1971, but were bypassed by the grand imperatives of the bicentenary. The organizers also wished humanely to spare Britain the melancholy task of hosting the Third World Congress of 1981, a distressingly apt title for the 1970’s. The Washington event was a great success, accompanied by the display of the Wyems copy of Magna Carta in the Capitol Crypt. I remember a splendid reception at the State Department, the court where Kissinger gloried and drank deep (as did numerous Shakespeareans). The Congress was brilliantly memorialized by Stephen Booth, in “Shakespeare at Valley Forge” (Shakespeare Quarterly).

That great event signified the nation’s deep commitment to Shakespeare. It effaced the memory of the absurd MacBird! (1967), a tawdry piece of counterculture posing as satire. President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, were proposed as the Macbeths who engineered the assassination of the previous ruler. Proper satire aims at real targets, and MacBird! does not rank alongside Juvenal and Swift.

But Ashley Thorndike’s claim is nowadays open to question, and the presidential devotion to Shakespeare may indeed be largely a matter of form. Still, President Nixon on Harold Wilson’s recommendation invited Nicol Williamson to perform a one-man show at the White House in 1970. Williamson was then regarded as the Hamlet of the era, and the show was a success. The actor Ian McKellen says that on one of his visits to the White House for a theater fundraiser, President Reagan recalled the words of “some wise old man”: “If only we could understand everything in Shakespeare’s plays, the world would be a better place.” McKellen was reluctantly impressed, until a few days later he heard the President address on TV a Baptist audience: “If only we could understand everything in the Bible, the world would be a better place.” So might a prominent Roman have gone along with the worship of Mithras. Obama is not ostentatiously attached to Shakespeare, but he hosted a White House party in which James Earl Jones delivered Othello’s Act One speech to the Venetian Senate. This is the scene where the Duke, in his final address to Brabantio, says of Othello, “If virtue no delighted beauty lack, / Your son-in-law is far more fair than black.” It is fair to assume that Mr. Obama wishes to be associated with the liberal side of Shakespeare. However, H.A. Scott Trask (“Choose Your Side,” Reviews, October 2017) writes in these pages, “There is no evidence that Barack, in college or out, has ever read, aside from an essay and poem by T.S. Eliot, a single work of Western history, philosophy, or literature.” I am not aware of a single production of Shakespeare that Obama attended during the eight years of his presidency. He did however visit, for 45 minutes, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre during his London trip of April 2016, when he paid his respects to the modern re-creation of Shakespeare’s most famous playhouse. Presidential affection for Shakespeare may be little more than a social mwa-mwa.

The real strength of the American Shakespeare lies outside Washington. Every summer, all over the Union, festival theater is put on. The great bulk will include in its program a Shakespeare play, that indispensable feature of summer stock. And many festivals acknowledge Shakespeare in their title. A short and incomplete list of these includes Shakespeare Festivals in Alabama, California, Houston, Kentucky, Long Island, Maryland, Nashville, Oregon, Riverside, Sacramento, and Pennsylvania. This is a tremendous, nationwide statement of belief and commitment.

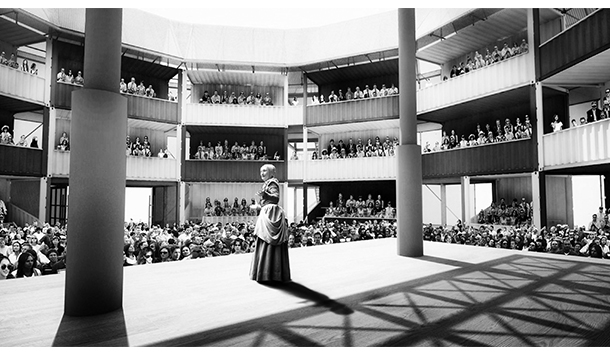

The historic triumphs of American stage and film celebration of Shakespeare are for another occasion. There are losses to report in the narrative: The American Shakespeare Theater in Stratford, Connecticut, once the great hope of American theater under John Houseman, no longer functions. Detroit’s Globe Theater has been talked of for many years but has yet to reach fruition, though a plan to erect a Globe theater built of shipping containers (The Container Globe) is a lively possibility. Detroit’s citizens have in any case first-rate exposure to Shakespeare: Across the border, the Shakespeare Festival Theatre in Stratford, Ontario, is in effect if not name the national theater of Canada. In its parking lot, 40 percent of all vehicles will bear a Michigan license plate. And we should acknowledge Harvey Weinstein’s responsibility as producer for driving through the wonderful film Shakespeare in Love, which won seven Oscars. It is as true now as when the New York Times made the claim 30 years ago: Shakespeare is America’s leading playwright.

Leave a Reply