I’ve long wanted to go to Cuba for the same reason that most Americans my age might. I wanted to see a place that has, for most of my life, been shrouded in mystery. It has been difficult for me to accept the idea that a country only 90 miles off our coast, home to more than 11 million people, is officially a “forbidden isle.”

I also wanted to ride in one of those vintage cars, now called “hybrids,” which are “old” only in outward appearance; I wanted to sit in the Floridita and sip a daiquiri, and smoke a Montecristo in the lobby of the Hotel Ambos Mundos, where Ernest Hemingway whiled away his off-hours between frantic scribblings and trolling for marlin. I wanted to wander around the Hotel Nacional, where Meyer Lansky and his Mafioso partners schemed, and visit the Tropicana, where Eartha Kitt and Frank Sinatra crooned. I wanted to climb to the top of the Bacardi Building; to stroll along the Malecón, the lengthy seawall across from Morro Castle, and view the gulf’s blue waters streaming by; to marvel at the idea that, just over the horizon, the blandishments of the American lifestyle were waiting.

For most Cubans, that 90 miles might as well be 9,000.

Mostly, though, I wanted to see Cuba as she is, before normalization of relations intrudes to change the country from how it is to how everyone, even those who are Cuban, thinks he wants it to be.

In recent years, scribbling visitors, mostly Canadians and Europeans, have tried to put a face on the people who live in Fidel Castro’s “Socialist Paradise.” I learned little from these. Individual prejudices colored the impressions and presented more veneer than veracity. Individuals who had personally visited reported that the food was terrible (and it pretty much is); that there was no air conditioning anywhere (and there pretty much isn’t); that there are hustlers and hookers prowling the streets—and there are those, too, but truly, no more than one can find in many neighborhoods in New York or, certainly, Las Vegas.

Of course, I had preconceptions. For most of my life I’d been schooled in the prickly relationship between Castro and the United States. I understood that many events ranging from the tense and tragic to nearly opéra bouffe had blistered our uneasy relationship. Overshadowing all of this, of course, was the open wound of “el bloqueo” (the embargo), now more than a half-century old, and the open hostility of Cuban-Americans, angry descendants of those who fled Castro’s revolution.

For decades, all of this has floated across the Florida Straits like storm clouds, occasionally raining down hurricane-force devastation on any hope of normalized relations.

I was prepared, then, to see oppression, prostitutes, and poverty, to witness hordes of  desperate, oppressed Cubans longing to take whatever chances they could to escape their island prison. I anticipated a tropical version of Cold War Eastern Europe, a Latino police state. I steeled myself to witness misery and endure hostility toward a hated yanqui, a child of capitalist opportunity, come to gawk at the suffering offspring of “communist tyranny.”

desperate, oppressed Cubans longing to take whatever chances they could to escape their island prison. I anticipated a tropical version of Cold War Eastern Europe, a Latino police state. I steeled myself to witness misery and endure hostility toward a hated yanqui, a child of capitalist opportunity, come to gawk at the suffering offspring of “communist tyranny.”

The first thing I learned when I arrived in Havana was that just about everything I thought I knew about Cuba, good and bad, was wrong.

As I wandered the streets of the historic district, Old Havana, as well as the central commercial (if one can use that term in a socialist country) area of downtown, I encountered bodega owners, doormen, elevator operators, bartenders and waitresses in the saloons and coffee shops, clerks in the stores, security guards, schoolteachers, bank tellers and policemen; I met teachers, laborers, waiters, taxi drivers, pedicab operators, and street artists. And, of course, musicians.

If Habaneros love anything more than playing music, it is talking about it, explaining how it is part of their culture and their lives. Rhumba, conga, cha-cha, folk ballads, and reggae fill the streets. The Buena Vista Social Club rocks every night behind septuagenarian performers who were entertaining when Fulgencio Batista was still in power. Musicians play on corners and in doorways—for tips, certainly, but just as often for nothing more than the enjoyment of passersby. “Guantanamera,” more or less Cuba’s unofficial anthem, and the romantic “Quizás” are perennial favorites, as, for some ironic reason, is the Sinatra hit “My Way.” To the Habaneros, music is a way of life.

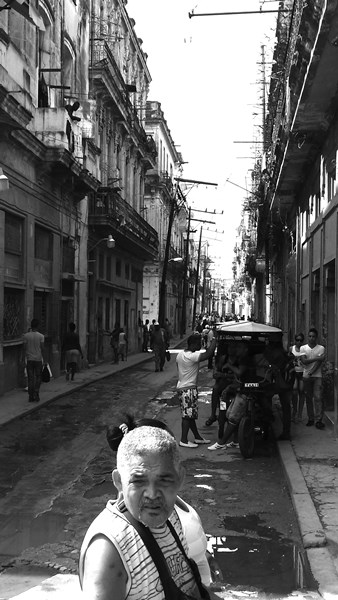

One of the greatest surprises was the general condition of Havana itself. The city of two million bustled. Traffic and crowds constantly hurried on the downtown boulevards. Parts of the urban area, though, looked like a former war zone or perhaps a city recovering from a devastating natural disaster. Upper floors were gutted, and some older buildings were closed. Utility poles leaned at precarious angles, and residential balconies sported chicken coops, drying laundry, and personal cisterns. There were derelict swimming pools with crumbling diving platforms rising above overgrown weeds, and abandoned factories behind collapsed barriers. Decrepit structures showed wear, deterioration, and, mostly, age. There was little new construction.

In the city center, around the capitol building and the historic district, renovation was under way. Most of the restoration, done by hand and with basic equipment, is hampered by a lack of money to fund many projects. After more than 50 years of neglect, the infrastructure is collapsing.

At the same time, there was no “urban blight.” Grass was sparse, but the streets, even in the poorer neighborhoods, were remarkably clean, although horses and dogs were everywhere. And everyone smokes. Everywhere. (It seems, as one of my companions put it, that it’s illegal not to smoke.) But there was no litter on sidewalks or streets. Every plaza and sidewalk was neatly swept. There was little graffiti. A few socialist slogans were evident, along with ubiquitous portraits of Che (never of Castro) and Cuban flags. There was a lot of artwork—murals, statuary, mostly devoted to Cuban history and culture. Booksellers offering used paperbacks and last year’s calendars, drawings, and prints surrounded the Plaza de Armas, along with street performers and caricature artists seeking Convertible Peso (CUC) tips.

There are shortages of most everything. Basic necessities are available, but fashionable extras are too expensive for the average Cuban. So is housing. No one rents in Cuba, at least not legally. Everyone owns, or such is the theory. This often means that multiple generations inhabit a single residence.

There is a lack of ordinary items: Toilet seats, ceiling fans, and bathroom tissues were conspicuously absent. Imported goods are prioritized, and such commodities are not deemed necessary. The philosophy seems to be “If you can live without it, you don’t need it.” Unfortunately, this makes everyday items ranging from guitar strings to magic markers difficult to find.

Most of the Habaneros I met didn’t seem overly concerned with material possessions. The musicians prized their instruments, and the hybrid drivers were so proud of their painstakingly restored vehicles that they didn’t mind passing up a fare merely to talk about the work they’d done on their ’52 Chevy or ’38 Ford. Those better employed earned higher incomes and dressed in more fashionable clothing, but none of the Cubans I met were in danger of prosperity. They didn’t complain. Mostly, they talked of better times to come “después del bloqueo,” something they all anticipated in the way that, it sometimes seemed, drought-stricken farmers look forward to rain.

Habaneros generally looked healthy and outwardly stress-free. During the day, many are idle, chatting and smoking in the plazas and doorways. All were uniformly polite, warm, and inviting, but never clingy or invasive. They offer a bright “¡Hola!” and a smile, maybe an offer to sell you something, especially black-market cigars, if you linger by a storefront. They are a fastidiously clean people who prize personal appearance a great deal.

They are also a “touching” people who will put a hand on your forearm or grab your fingers in a gesture of intimacy that can be disconcerting, until you realize that there’s no harm in it. They can be aggressive in approach, but there’s no sense of self-parody, as one often finds in the tourist traps of Mexico or Europe. They take no for an answer and greet negative responses with a casual shrug.

Habaneros seem to embrace their identity. They see themselves as Cubans first, Caribbeans second, Latin Americans third. The distinction is important.

I gradually came to see that Cubans are very comfortable being who they are, in their own skins. They seem to have taken the worst that life can throw at them and made more than the best of it. They exhibit a strong sense of pride in their lives, even when they are recounting some sad event—such as the loss of a spouse, which one teacher told me about. In the next moment, she happily displayed photographs of her children. I detected no sense of fear or of persecution, and no despair. There is want—that much is clear—but no revealed resentment of others who have more.

Cubans seem to endure much less regulation and oppressive oversight than one might imagine in a totalitarian nation. They would be utterly confused by such sanctions as  smoking restrictions, mandatory seat belts, regulated alcohol sales, and tamper-proof packaging. One afternoon, a girl of about eight or nine in a school uniform came into a bar where I was enjoying a Cuba libre and climbed up onto a stool. Producing a notebook and a pencil, she summoned the bartender, ordered a cola, then proceeded to interview him about his job. He answered seriously and politely; she took careful notes and drew a quick sketch of him standing behind the bar. Then she thanked him and left, threading her way among the other patrons. I tried to imagine this happening anywhere in America.

smoking restrictions, mandatory seat belts, regulated alcohol sales, and tamper-proof packaging. One afternoon, a girl of about eight or nine in a school uniform came into a bar where I was enjoying a Cuba libre and climbed up onto a stool. Producing a notebook and a pencil, she summoned the bartender, ordered a cola, then proceeded to interview him about his job. He answered seriously and politely; she took careful notes and drew a quick sketch of him standing behind the bar. Then she thanked him and left, threading her way among the other patrons. I tried to imagine this happening anywhere in America.

There’s also a strong sense of pragmatism and personal responsibility. At one point, observing a large excavation project in Old Havana, where pedestrians were stepping over a four-foot-wide trench, I noted to the supervisor that, in the United States, such a project would be surrounded with safety barriers and warning signs. He responded, surprised, “What’s the point? If you can see the sign, you can see the hole.”

As I met and engaged the Habaneros, it became apparent that the desire for normalization is always close to the surface. They imagine the transformation of a place where little is obtainable to a world where everything they might desire—largely from watching American films and television—is abundant. They envision shops filled with the latest fashions and electronics, plentiful and cheap food, where luxury is taken for granted. They don’t understand that not everyone in a capitalist society can afford everything he wants, and that the poverty rates in many nations—including the United States—are high and good wages hard to come by.

Cubans currently enjoy high-quality and totally free health and dental care and free education for anyone who is willing to study hard and advance. Newly instituted but limited free enterprise is permitted by the government and provides Cubans with a sometimes profitable outlet for their ideas and initiatives.

Yet personal freedom is limited, and there are governmental, military, and social obligations. Choices are restricted, as is the ability to travel or live and work where they want. But officially, at least, no one is starving, no one is homeless, and no one is visibly subjugated. Gay marriage is approved, abortion is legal, gun ownership is not. Violent crime is the lowest in the hemisphere, and so is per capita incarceration.

What Cubans don’t realize is that a lifting of the embargo would bring in a flood of American- and Chinese-made consumer goods; it would also bring in a tidal wave of cultural change. At the moment, Havana exists in a kind of bubble, stuck in the early 60’s, reliant on antique amenities, many salvaged from the old regime. Films shot in that period—Our Man in Havana, for example—reveal a place that looks the same in many aspects as it does today, especially the vehicular traffic. That wouldn’t be the case in Paris, Rome, London, or certainly any city in the United States. Monuments and landmarks may remain the same, but those cities’ backgrounds are shaded by modern construction and the homogenizing influence of globalization.

There are small indicators of modernity—skinny jeans and Nikes, pedicures and cargo shorts—but these are not typical. There are no cellphones on the street, and personal computers are rare. One doesn’t have to imagine yesterday in Cuba; it’s in plain sight.

Far from living in fear, Habaneros speak of Fidel (and he’s always “Fidel,” never just “Castro”) as if he were a funny uncle locked away for his own (and maybe their) protection. Raúl is similarly regarded. Politics plays a small role in their lives, and however much raw want burdens daily existence, they maintain self-esteem. They say what they want, openly and without fear. They have maintained or created their own religious foundations, even elevating the uniquely blended Santería cults to a national phenomenon that is part religion, part entertainment, and all joy. Their devotion to literature is amazing in a world where print publishing is dying. Cuba claims the highest literacy rate in the Western hemisphere, maybe in the world, and the Cuban film industry is generating motion pictures at a manic pace.

Everywhere I turned, there were public displays of art, architecture, and style showing no corruption of contemporary outside influence. Mixtures of Spanish and other European, Latin American, and African bloodlines have amalgamated into a social mélange that has produced a racially diverse, genetically mixed, and often physically beautiful people who, at least officially, do not tolerate discrimination or distinction. Personal prejudices doubtless exist, but in the streets of Havana, people of multiple backgrounds are mingling, both in their everyday commerce and their personal lives.

The result is a kind of social laboratory, thriving in a kind of vacuum, partly self-imposed, but mostly the result of international isolation. Their culture is vigorous, fluid, and expansive. It’s also exceedingly fragile, vulnerable. Any modification, however slight, could taint the whole.

For the moment, though, it’s just plain unique—there is no other word for it. And to an American, born and bred in the capitalist-enriched world of Baby Boom prosperity, it makes Cuba a fascinating place to visit, although I cannot imagine living there.

When (it’s not really a matter of if) normalization occurs, Havana in particular will be totally altered. Within a very short time Starbucks, McDonald’s, Domino’s, and KFC will spring up like weeds in a fertile garden, erupting on every corner and choking out the patented Cuban bodeguitas with something commonplace and indistinct. Already, plans are under way to move the industrial docks of Havana’s harbor up the coast, making room for marinas, clubs, and restaurants along the Avenidad del Puerto. In short order, Hiltons and Marriotts with their attendant casinos will overlook the Malécon, and Walmarts and Home Depots, Costco and Old Navy, will displace the tiendas that pockmark every Cuban street. The hybrids might survive, but only as collectible curiosities when efficient new automotive models arrive. The famous Cuban guayabera will be replaced by Polo and IZOD; how long before Victoria’s Secret opens up?

Beyond goods, the contamination of alien culture will come in with fury. Western pop music will replace authentic Cuban tunes, reducing them to the kind of imitative attractions one finds in the mariachis strumming away in any Mexican restaurant. Native art will give way to trendy chic, and modern design will reflect the latest style, rather than the impulse to connect to the past, near or distant. Universal Wi-Fi and social media will have a devastating impact on a society that presently prizes personal conversation and print publishing. In no time at all, Cuba will devolve into what’s hot, what’s immediate, what’s disposable and forgettable.

As tourism grows and flourishes, Cubans will reel from regulation of everything touching their personal lives. Antique buildings with their quaint narrow staircases and unrestricted balconies will be modified for convenience and safety, windows will be sealed to contain refrigerated air, and oversight of everything from childcare to food processing will be severely imposed. Horse-drawn carts and the trademark urban dogs will disappear, serious crime will increase, and the price of everything, no matter how high it may be at present, will go up. Education will decline, litigation will rise, and corruption, never completely absent, will soon dominate.

Such change, again, is inevitable. When relations between Cuba and her largest and nearest neighbor—a nation with which she increasingly shares a common language and, oddly, many elements of social and cultural history—are established, the normalization of Cuba will be so rapid, so extreme, that it will be hard to remember what Havana was like before Castro—or even under him. One wag opined that after normalization Havana will look “just like Cancun.”

I disagreed: It’s more likely to look like San Juan or Kingston.

Communism is an horrific system, and socialism is by no means the best economic structure. Capitalism may be the most advantageous pathway to national prosperity, but the fallout can be devastating when the gap between the haves and have-nots suddenly widens, and a society’s culture hangs in the balance.

At the moment, nearly everyone in Cuba is in the same boat. There are only a few who enjoy privileges and power that the masses do not have, although this is changing as limited access to the CUC is allowing a new bourgeoisie to emerge. Still, those who work the hardest and prove the most diligent are rewarded with more, but even those who don’t are taken care of. Frustration is the hallmark of the ambitious, the accomplished, those who dream of a better life. Complaint can only soothe the ego; it can’t improve the status quo.

As Habaneros sit around their tree-shaded plazas and their bakeries and bars, listening to their own music, sipping espresso, drinking mojitos and daiquiris, smoking their famous cigars, considering the depravation of a lifestyle that has been forced on them merely to prove a political point, they fail to understand the price of their fondest wish. Unfortunately, it will be Havana itself. In spite of the scarceness and want they endure, they have no idea what they will experience when a completely different and sometimes rapacious global culture will intrude, bringing with it an end to the authenticity of their carefully nurtured identity.

[images courtesy of R. Clay Reynolds]

Leave a Reply