Bolling Hall has squatted on its plot since the 14th century, hunched against the wind and rain of the West Riding—a North Country architectural essay in dark yellow sandstone looking warily down a steep hillside onto Bradford’s Vale. Old though the building is, the estate’s foundations go deeper than Domesday, when Conqueror companion-in-arms Ilbert de Lacy abstracted it from someone called Sindi, his reward for sanguinary services rendered during the Norman invasion and the subsequent Harrying of the North.

De Lacy’s motte-and-bailey has been overbuilt, and his line is long extinguished, but other owners likewise felt the need to guard against restive locals, rival families, religious opponents, apolitical marauders, wolves, the Great Boar of Cliffe, and whatever other elementals might watch and wait from tangled woods, stony slopes, and bog-cotton dancing moors. The family crests of manor-holders, scratched in black and white onto a window lighting the stairs to the Ghost Room, constitute a subfusc sort of heraldry, one informed by everyday sights as much as by classical or chivalric conceits. There are martlets for the Bollings and Tempests, oak trees for the Thorntons, owls on a bar sinister for the Saviles, cudgel- and shield-bearing wodewoses for the Woods, hunting horns and chevrons for Bradford. They feel like the arms and achievements of provincials attuned to rurality and modest in their pretensions—although Robert Bolling overreached himself during the Wars of the Roses and was temporarily deprived of the estate. (A later Bolling, Edith, married Woodrow Wilson.)

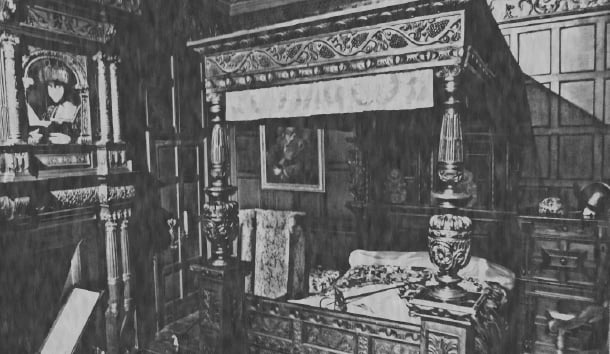

The oldest part of the present building has been identified as a pele tower, although these are more usually associated with points yet farther north, in the “Debatable Lands” between Scotland and England. Yet pele towers are likely enough in this valley long accessible only from the north, where the laws of London or even York held only spasmodic sway. Even with later fenestration that streams grayness into the Great Hall, and Adam-style remodeling, Bolling keeps a fortress feel, a sense augmented by dark Jacobean paneling cut deeply with geometric patterns, strapwork, acanthus leaves, flowers, birds, and lions’ heads, interspersed with rubicund oils of English faces, and even a death mask of Cromwell. The hall possesses what the poet-topographer Peter Davidson calls “northern rooms, rooms that expect nothing of the weather.” It could be a Hollywood haunted house, and indeed there is a legend attached to the Duke of Newcastle who slept here in December 1642 on the night before his planned attack on the almost defenceless Parliamentarian town. Bellicose before retiring, he came down palely the morning after, claiming he had been visited by the apparition of a weeping woman begging him to “Pity poor Bradford.” Whether genuinely believing he had seen a specter, or just hung over, the Duke marked his martial descent of that day by relative restraint, with just ten deaths recorded.

The defenses of Bolling never needed to be tested, but enemies of an odd kind came upon it anyway, creeping up its hill in increments of meaner dwellings, so that now two aspects of the hall look onto semis and a car park, and there is a noise of traffic where once one would’ve heard bleating or birds. But this civic slight is in its way appropriate, in this region where melancholy falls as readily as rain.

Sometimes it seems almost a requirement to portray the North of England as a single vast and tragic landscape. The imaginative equation of north with dearth goes back as far as Roman legionaries tramping gloomily up the Great North Road to garrison the edge of the empire at Hadrian’s Wall (although Septimius Severus died at York, and Constantine took the purple there). It gathered pace as the locus of English power slowly migrated south, as monarchs roamed their realm less frequently, ecclesiastical power centered on Canterbury, and parliaments fixed at Westminster. The great families of the North found themselves becoming provincials—and slightly untrustworthy ones. From the London point of view, they had too often been kingmakers or -breakers, too often Catholic, too rich, too swaggeringly insolent, and their centers of learning at York and Durham were cultural as well as temporal rivals.

The Tudors unroofed the great Cistercian abbeys of Jervaulx, Rievaulx, Fountains, and Byland, gelded the prince-bishops, and started to centralize the legal system and house-train the Percys, Howards, and Cliffords. The North was just too close to Scotland to feel fully safe, and even after the crowns were united in 1603 long-standing fault lines remained. Well into the 18th century, the North was seen as marginal, outside the English mainstream, a redoubt of recusancy potentially sympathetic to Stuarts, its untrammeled nature offending against both the logic of the Age of Reason and the aesthetics of the Age of Taste. Even when the beauties of Lakeland began to be discovered by poets, aquatinters, and garden designers, they were slightly shivered at, seen as unreal, unpeopled, dubbed “horrid” or at best “picturesque”—places to be looked at rather than lived in.

The Industrial Revolution eventually made the North central to the English economy, making vast amounts of new money while undermining the aristocratic order—in a few cases literally, with landowners delving for coal almost under inherited houses. When the borough of Bradford came into being in 1847, it contained no fewer than 46 coal mines. The municipal motto was Labor Omnia Vincit, and in Bradford furnaces blasted day and night, chimneys choked, hammers clanged, and cogs clicked, mills clattered and drifted lung-filling fibers—and 30 percent of all children died before attaining their teens.

The ugliness associated with industrialization actually reinforced Southern notions of the North as a place apart. From the safe South, Northern towns were increasingly seen as the haunts of grim-visaged Gradgrinds, building themselves vulgar villas while turning sturdy peasants into sickly slum-dwellers. Beyond the ragged edges of the ever-expanding towns, the savage scenery of moors seemed perfect habitations for Heathcliffs, ideal locales for a hundred Dotheboys Halls. The Devonshire-born Nicholas Nickleby’s reaction upon first seeing Wackford Squeers’s appalling academy is one of a Southerner feeling suddenly very far from home: “As he looked up at the dreary house and dark windows, and upon the wild country round, covered with snow, he felt a depression of heart and spirit which he had never experienced before.”

The names alone of places and people sound stark—Blubberhouses, Mytholmroyd, Uriah Woodhead, Savage Crangle, Hardcastle Crags, the ominous Nab Wood Cemetery and Crematorium, and countless others. Wanderers are furthermore constantly being arrested by disquieting associations, such as the plaque in smart Skipton that indicates the Bull-Baiting Stone, or an antlered bronze demon looking saturninely out of a sunny New Age shop window in the same town, faintly disturbing among the trash of tarot. Such things can be seen in the South too, but they seem to have an extra level of significance against a backdrop of low-lit moors and sharpened by frost.

Nouveau-riche mill-owners, mine managers, and middlemen aped aristocratic manners and manors, attended ostentatiously at chapel or Low Anglican services, endowed and administered charities, but were typically seen as bumptious, unlikable, and unscrupulous. However irreproachable many may have been, even when they were like Titus Salt, they were easy targets for either snobbish satire or socialistic critiques such as the Bradfordian playwright J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls, in which a mysterious detective turns up late at night to quiz the inhabitants of a huge new house about the suicide of a local girl, exposing the callousness of the family and their recently risen class.

Even now, with the old industries at last starting to be replaced, to the Southern English mind, the simple words “The North,” as glimpsed so frequently in Transport Medium typeface on road signs, connote both stonewalled fields and urban decay, poverty, grimness, and lostness—to which can now be added vague but not unfounded notions of dangerously alienated Muslims. Anyone who ventures north of the significantly named “Home Counties” soon realizes that this stereotypical view effectively means West and South Yorkshire, and Lancashire and Tyneside conurbations. The vaster Yorkshire comprising the lonely landscapes of the North Riding, and the semisubmarine East Riding with its drowned towns and dreams of the Hanse, not to mention history-clogged York itself, does not really enter into this equation. Nor do the Lakes, Durham Cathedral, the walls and rows of Chester, Carlisle, Liverpool, or Northumberland—all of them of course in the North, but not intrinsic to that particular understanding.

The Industrial Revolution itself has become the object of nostalgia as its rawness mellows into Grimshaw and Lowry tones, and the uncompromising communities that coalesced around milling, mining, or steel are seen through a prism of foxing monochrome stills from the 1930’s through the 1980’s. Guardian journalists still (and with justification) bewail the economic hollowing-out caused by Thatcherism, the once-powerful industries sacrificed to City of London speculators, steel, mining, and milling workers fly-tipped into an abyss of welfare dependency and social squalor. Leftists take a special interest in Bradford because of its exploitative past, its innovations in education and medicine, and its role in the foundation of the Labour Party in 1893. (The present government is trying to make political inroads hereabouts by talking of “Northern powerhouses,” with devolved powers and better railways—suitably Victorian solutions for a town of phlegmatic traders.)

Leftists who emote about the North rarely have practical ideas as to how global economic trends can be reversed, and also tend to be uninterested in the Immigration Revolution that accompanied de-industrialization and exacerbated the area’s social splintering. To them, it seems of little consequence that a quarter of Bradford’s 523,000 residents are Muslims, many cleaving to ultraorthodox interpretations. Perhaps somewhere now in the city there are a few more idealists like Tanveer Ahmed, who in March went all the way to Glasgow to murder an Ahmadiyya shopkeeper who had “disrespected Islam” by wishing a Happy Easter to Christian customers. Immigrants have long been attracted here by the wool trade, which once made Bradford the “wool capital of the world” but had gone into irreversible decline by the time the first Asians arrived. The new immigration was therefore badly timed as well as different qualitatively from the European incursions of the mid-19th century onward (whose most unlikely product must be that composer of lush tone poems Frederick Delius, who lived in the district still called Little Germany).

To a certain Panglossian kind of commentator, the race riots of 1985 and 2001, and the public burnings of The Satanic Verses in between, were passing epiphenomena, regrettable but understandable products of low education, unemployment, Tory cuts, and social segregation caused chiefly by white racism. They would rather focus on such heartening factoids as that Bradford was declared “Curry Capital of Britain” in 2013; that nearby Hebden Bridge is a louche home to an unusually high number of lesbians; that Heathcliff was a victim of anti-Roma prejudice, and his creator of “gender” inequality; that the town had critical ethnic mass to host the 2007 International Indian Film Festival awards.

They would also be largely indifferent to the epic echoes of the premodern county, its still visible castles, churches, halls, and houses, its mental habits and myths. If they were to visit Bolling, they would be most interested in the working conditions of turnspits. At Skipton Castle, they might glance up at the grand gatehouse, with its forward-looking family motto Désormais (“Henceforth”), but they would not find it strangely sad that Lady Anne Clifford, who placed the hopeful word there c. 1649, would be the last representative of a dynasty that had once commanded allegiance

From Penigent to Pendle Hill,

From Lenton to Long Preston

And all that Craven coasts did tell

They with the lusty Clifford came

Well brown’d with sounding bows upbend

On Clifford’s banner did attend.

What could neo-Puritans comprehend of the experiences or motivations of the likes of Anne, who held the castle three years for the King, or even bloodier-minded ancestors like Robert Clifford, who entertained Edward I and who chose to live in this dangerous zone so that he would never miss an opportunity of fighting the Scots? Another was John Clifford, who had already earned the nickname “Black-Faced Butcher” by the time he fell at Towton aged just 26. Even the most peaceable of the tribe, Henry (called by Wordsworth the “Shepherd Lord” because of his long exile in the hills), led the Craven contingent to victory at Flodden. No doubt all these would be adduced as arguments for historical inevitability, products of the irrational military-aristocratical complex, yet more reasons that order had to end. As for the Saxon high crosses in the church at Ilkley, with their writhing beasts and worn Jesus, they would be seen as stelae marking the resting places of ancient delusions—a disdainful sort of analysis for some reason never extended to the ideas expressed in the West Riding’s mosques.

And what would urban chatterati make of Yorkshire’s underlying nature, its hard-edged pastoralism, its sudden stabs of beauty, more evident again now that mines have been backfilled, mills become apartments, and waterways transport fewer toxins? What would they think of if they were to walk under the sky-supporting arches of old abbeys drowsing along peaty rivers, knee-deep in summer flowers, their hedges silver-spangled with cobwebs on frosty mornings? Probably just that this was the inevitable end of an unsustainable system. They might smile at Geoffrey Hill’s playful poem, “Damon’s Lament for his Clorinda, Yorkshire, 1654,” which subverts urban and proletarian associations by projecting Arcadian and Renaissance imagery onto a winter’s day during the endless-feeling English interregnum:

November rips gold foil from the oak ridges.

Dour folk huddle in High Hoyland, Penistone.

The tributaries of the Sheaf and Don

bulge their dull spate, cramming the poor bridges.

The North Sea batters our shepherds’ cottages

from sixty miles. No sooner has the sun

swung clear above earth’s rim than it is gone.

We live like gleaners of its vestiges

knowing we flourish, though each year a child

with the set face of a tomb-weeper is put down

for ever and ever. Why does the air grow cold

in the region of mirrors? . . .

But the best-known poet celebrant of Yorkshire is Ted Hughes, whose most relevant collection for these purposes is his 1979 Remains of Elmet, honoring the little kingdom that rose and as unostentatiously expired in what is now West Yorkshire some time between the fifth and seventh centuries. The collection is as elegiac as the title suggests, and in some respects is itself rather dated. But “The Trance of Light” looks both back on a semimythical shire where small kings and Great Boars really did coexist, and forward to a day when the last looms and Low Churchers go down to join the ancient Britons, the pinched life ends, and Hughes’s beloved hawks can once more clutch creation in their claws:

The upturned face of this land

The mad singing in the hills

The prophetic mouth of the rain

That fell asleep

Under migraine of headscarves and clatter

Of clog-irons and looms

And gutter-water and clog-irons

And clog-irons and biblical texts

Stretches awake, out of Revelations

And returns to itself.

So superb to think that it might, and that something substantive remains among all these layered remains.

Leave a Reply