The town of Penza lies 12 hours southeast of Moscow by train. I had barely heard of it before I went there last December. The town’s broad streets were busy yet strangely silent because of the thick carpet of snow that dampened all sound. On the river Sura, fishermen sat huddled in the dark over holes they had cut through the ice.

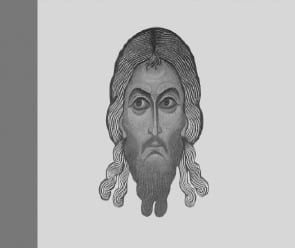

Penza is much like other provincial Russian towns: Laid out on a grid, its streets are full of the modern clutter of shop awnings, while the people are well dressed. There is a comforting sense of normality. One thing, however, distinguishes Penza and its region (which is one of the 83 units of the Russian Federation) from every other political entity on the Eurasian continent. Some years ago the regional authorities decided to adopt as their official logo a 12th-century icon of the Holy Face. Jesus Christ therefore flutters from administrative buildings all over the place.

The decision to do this was not unaccompanied by controversy, but it went ahead. It is a decision that is completely unimaginable in the West. American separation of Church and state and rampant secularism in Europe (to be more precise, hatred of Christianity) make such a choice unthinkable in countries like Britain, where a British Airways employee is still being persecuted for wearing a small crucifix on a chain round her neck, or Italy, where the European Court of Human Rights recently banned crucifixes in Italian classrooms. (The ruling was overturned on appeal, but only in the name of a politically correct appeal to “Italian culture,” as if the crucifix were some sort of tribal totem.)

Penza’s adoption of the Holy Face may be unique in Russia, but it is nonetheless indicative of a state of mind in that vast country that is the opposite of the mind-set of the West. To be sure, abortions proceed in Russia at a terrifying rate—about one million per year, which is proportionately over twice the rate of even an aggressively abortionist country like Britain, and which goes a long way to explaining Russia’s low birthrate—and therefore it would be foolish to imagine that Christianity somehow penetrates all Russian souls. But when the girdle of the Virgin was brought to Moscow from Mount Athos last November, the estimates of the number of people who turned out in the sleet and the snow to venerate it varied between one and three million.

Such figures put in perspective the paltry 50,000 or so who demonstrated in December in central Moscow against Vladimir Putin and his United Russia party. Despite the small numbers, and despite the fact that the other planned rallies in the provinces were a damp squib, the Western media seized on these demonstrations to announce with one voice the crumbling of the Putin “regime.” They are still talking about them now, three months later, hopelessly in hock to their fantasy that Putin’s opponents are liberals like themselves. Inhabiting a parallel universe in which the wish determines reality, they deliberately chose to ignore the sea of black, yellow, and white flags in the crowd in Moscow on December 25—the old Russian imperial colors adopted by Russia’s vocal fascists who want ethnic cleansing of Muslims from Moscow and the expulsion from the federation of the Muslim-dominated Caucasus states. For the Western media, any enemy of Putin is a friend.

These extreme nationalists are only the thin end of a very thick wedge of extremist opponents to Putin. Not only is there no serious doubt that Putin is genuinely popular; there is also no serious doubt that this is for a very good reason—namely, that the alternatives to him are terrible. Are those Western commentators who call Putin a dictator saying they would prefer the man who came in second, Gennadi Zyuganov, leader of the Communist Party, which won 20 percent of the vote in the parliamentary elections in December? Do they expect a friendly Russia from this man who breathes fire every time NATO or the West is mentioned? Or what about Vladimir Zhirinovsky, Zyuganov’s opposite number on the extreme right, the vulgar buffoon who has spent 20 years repeating his party piece, which consists of a lot of eloquent and sometimes obscene shouting at his numerous opponents? He came in fourth in the March poll while his party polled third in December. Or is their cult of youth so blind that they prefer to these retreads—who had been leading their respective parties for a decade before anyone had heard of Putin—the jack-in-the-box candidate who appeared from nowhere, Mikhail Prokhorov, who in his early 40’s has amassed a fortune three-times larger than that created by Silvio Berlusconi after a lifetime of hard work? Berlusconi was an accomplished politician by any chalk, whatever his faults, yet his enemies always attacked him because he was rich. Why would a multibillionaire nickel magnate like Prokhorov be a man of the people if the Italian media boss was not? In short, Russia’s leadership might appear to be a monolithic cartel (Putin was first appointed prime minister in 1999), but the Russian opposition is a freak show.

To be fair, the hatred of Putin is not confined to Western liberals. Russian liberals share it, too. On a BBC World Service phone-in on which I spoke two days after the presidential poll, one particularly virulent lady from Moscow combined the conspiracy theories of the outer fringes of the internet with the aching snobbery of the metropolitan intellectual: Introducing herself as “a scholar,” she told the listeners that Putin’s voters are simply idiots (“They have no head”), while the man himself was responsible for every ill from the sinking of the Kursk to the hot weather in 2010. The BBC would never interview a man in a log cabin in Montana who thinks that George W. Bush blew up the Twin Towers, at least not deferentially, yet this woman’s ravings were listened to with respect.

The hatred, of course, is not ultimately of Putin nor even of Russia. Its particular obsessiveness can be explained only by deeper causes—namely, a hatred of self. Russia is very obviously a European nation, but one which often follows a different path from the rest of Europe. She is also too big and too independent to be integrated into it. These things infuriate the “pro-Europeans” in Europe—those people who are determined to finish off any idea that Europe is a family of Christian nations and set up a postmodern, godless, and cosmopolitan nonstate supposedly along American lines. No issue crystallizes the difference more clearly than that of homosexuals, which has become the litmus test of self-destructive postmodern values: the recent ban by Saint Petersburg on homosexual propaganda, and Moscow’s stubborn refusal to allow gay-pride marches, have infuriated the guardians of political correctness in the West, in exactly the same way that Mrs. Thatcher’s laws against the promotion of homosexuality did in the late 1980’s. The difference is that Britain’s Conservative prime minister today is in favor of gay “marriage.”

To see that democracy or human rights have little to do with the persistent bad blood between Brussels and Washington, on the one hand, and Moscow, on the other, we need only consider the extreme cordiality accorded to the Chinese vice president, Xi Jinping, when he visited Washington, D.C., in February. That an aged Henry Kissinger was wheeled out to meet him emphasized the continuity of U.S. geopolitics since the height of the Cold War (support China to counter Russia); that the champagne was wheeled out so that those great human-rights activists Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden could toast the future head of the world’s biggest one-party state emphasized that the West will turn a blind eye to a rising great power, provided it is non-European, but never miss a trick when it comes to running down the West’s geographically and culturally immediate neighbor. This is civilizational suicide in real time.

There are more banal reasons, too. For all its weaknesses and internal problems, Russia remains the only country in the world that can ever hope to thwart the West’s determination to create a unipolar world. China tends to hide behind Russia’ skirts when it comes to vetoing Western interventionism in the U.N. Security Council, and in any case it is Russia that has the firepower. Russia—President Putin himself, but also his immensely able foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov—has formulated with admirable clarity the case for noninterventionism and multipolarity, for instance over Syria but also generally, and this ever since Putin’s remarkable speech to the Munich security conference in 2007. The fact that it was President Medvedev who fought the war against Georgia—a small war with huge geopolitical consequences, namely, that neither Georgia nor, by extension, Ukraine, will now ever join NATO—has done nothing to dent Putin’s reputation as the brains and the power behind his short-lived presidential nominee, and this is why Obama’s “Reset” of relations with Russia, announced in 2009 and partly implemented, has deteriorated into a full-scale computer crash ever since last September, when Putin announced he would run for the presidency again.

By the time Putin comes up for reelection, it will be 2018. Obama, Cameron, Sarkozy, and Merkel will have all been forgotten. Putin would have been up for a constructive relationship with the West, including with the United States, but he has been spurned so much now that any attempt to repair the broken relationship, even if one were made, would probably founder. Decades after the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the West’s leaders are likely to remain determined to push Russia out of Europe in order to unify the Western edge of it. The plan, indeed, is much as it was 200 years ago, when in early 1812 Napoleon wrote to Joseph Fouché to explain that his goal in attacking Russia was to unite Europe:

Think of the war against Russia as a war of common sense, for our true interests and for the peace and security of all . . . We need a European code, a European court of appeal, a single currency, the same weights and measures, the same laws. I must make one people out of all the peoples of Europe. That, Sir, is the only outcome which suits me.

Leave a Reply