Sitting at Mass in St. Theresa’s Church on Camp Street in New Orleans some six months after Hurricane Katrina, my eyes rise naturally above the altar. There, I see a large, ugly panel of various sheets of plywood and two-by-fours filling the vast hole where the fine old stained glass depicting an incident in the saint’s life once was, before it was blown out during the storm. And, as this is a small, poor parish, odds are, it will never be replaced. The one panel that remains includes the state seal of Louisiana, a round emblem enclosing the image of a pelican feeding her young. This view reminds me of the condition of this city and surrounding parishes hit by Katrina; many areas are still an ugly reality of wrecked houses and uncollected trash, while people cling to the illusion of an unfathomable belief in the powers of the god of the State—not the one in Baton Rouge, of course, but that in the District of Columbia—to cure all ills.

A month or so back, we went downtown to St. Louis Cathedral and heard Archbishop Hughes warn that people should be very careful how they inject race into the dialogue about rebuilding the city. One man in attendance that day—our mayor, Ray Nagin—was apparently not paying much attention, as the very next day, Martin Luther King, Jr., Day, was the occasion of his famed pronouncement, “and I don’t care what people are saying Uptown or wherever they are. This city will be chocolate at the end of the day.” Interestingly, almost all of the commentators on that speech neglected to include the opening qualifier. And it was a rather odd thing for a black mayor of New Orleans to say, with the implication that everyone uptown is white, ignoring the reality of the many black neighborhoods uptown, such as Central City, “Gert Town,” “Black Pearl,” and large sections between Magazine Street and the river. But our mayor does not really care about fine points, after all, and has revealed himself to be as crass a panderer as any of his fellow politicians, catering to whatever audience is at hand—as in his recent comment about his mostly white rival candidates (“not many of them look like us”) to an NAACP meeting in Houston.

There are still no streetcars on St. Charles Avenue, but things are otherwise sort of back to normal. A friend of mine said that, the other evening, just as he was about to get on a St. Charles bus after work, he saw a fight break out on the bus and heard kids screaming, “He’s gonna stick him!” Seconds later, he saw them jump out in panic after the stabbing, while the bus driver, a large black woman, huffed repeatedly, “I’m gonna bitch-slap somebody!” I caught one of those buses up to the doctor the other day and noticed that the Rite-Aid on Louisiana and St. Charles still consists of a trailer parked in front of the defunct pharmacy. A large sign stuck on the trailer proudly says, “Welcome Back New Orleans.” Rite-Aid is not alone in displaying its optimism. A 40-plus-story-high banner elegantly draped over the still mostly shredded windows hangs off of the Hyatt hotel with the slogan “Let the Good Times Roll” in misspelled French.

By the way, the buses here, a motley fleet, some brought in from other towns still sporting destinations to streets not even in this city, are free until June because, apparently, the federal government (under the aegis of FEMA) cares more about subsidizing a private company than about doing the job it is supposed to do—that is, delivering mail. Last week, six months after the storm, I called the U.S. Post Office for the third time in frustration at not being able to get much mail at my bookstore in the French Quarter, an area that never flooded. (I conducted a book swap the day after Katrina and reopened on September 30.) They admit not even trying to deliver any third- or fourth-class mail in the city until, well, who knows when. I was told on a return call by a local customer-service representative that, before regular mail can be delivered, “we’ve got to get our people home.” A similar theme was heard in the first televised mayoral debate the other night, with most candidates pining over getting everyone back. Only one, the sometimes strident, if wonderful (and completely unelectable), former city councilwoman Peggy Wilson, challenged that consensus, saying that there are some types of people we don’t want back—namely, the drug addicts, the gangs, and the welfare queens. Ah, how well I remember watching one of those welfare queens point out exactly which car she wanted stolen by her boys in front of my apartment building two blocks from the Convention Center on that terrible Thursday after the storm.

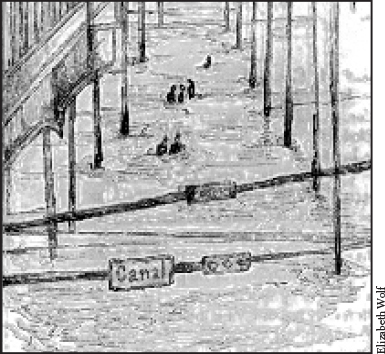

I also remember how, after the news broke that Jefferson Parish president Aaron Broussard had let the pump workers leave their posts to run for shelter before the storm, causing incalculable damage to that community, my wife suggested how symptomatic that was of exactly what is wrong with this country—that is, it is all about self-interest without any concept of a larger public or civic duty. Who cares that the pump workers were there to protect the whole community—let them go home! Who cares that a full third of the New Orleans police force seems to have disappeared during and after the storm—those that stayed were not much help, anyway. I crossed Canal Street six times in the days after Katrina and saw groups of policemen standing around gabbing while shops were being looted nearby. Although the main entrances to the two most important sales-tax-generating properties in the city, the shopping centers One Canal Place and the Riverwalk, were both literally across the street from the police command post established at Harrah’s Casino, both were heavily looted, and one of them was set on fire. But who cares? Obviously not New Orleans’ finest. There is a T-shirt selling here now that pokes fun at this sad situation, changing the initials N.O.P.D. (New Orleans Police Department) to “Not Our Problem, Dude.” And the stories of coordinated looting by the police themselves are too numerous and detailed to be denied, though but a dozen officers have been indicted for such crimes (if we don’t count the one New Orleans cop caught in Houston driving a stolen Cadillac SUV). So much for honor, duty, and civic pride.

What continues to strike me above all about the subject of Katrina and its aftermath—both the natural disaster and the human disaster that followed, encompassing the total failure of the police department, the total abandonment of the city by the mayor, the very un-American forced evacuation of perfectly dry, livable areas after the storm (and the deprivation of food and running water to those who tried to remain to protect their property), the subsequent looting, fires, and just general chaos—is not how specific the situation was to this place but, on the contrary, how common it could be, how easily other large urban communities could suffer the same fate given some similar natural disaster, terrorist act, or epidemic. It could happen anywhere: the bungling bureaucracies, the spineless politicians, the corrupt police, the entitlement class hovering about, just waiting for their chance to break the law with impunity. Nor is it something new. Something quite like it happened some one-hundred-and-thirtysomething years ago in supposedly the most civilized city on earth—namely, the looting and destruction of wealthy properties by the poor during the Paris Commune of 1871. What large urban center in this country is not under the dormant threat of a permanently entitled class anxious to exploit every conceivable opportunity to get something for nothing? And is this really that surprising, in a society in which so many state and municipal governments have encouraged such an idea for so long by their profligate support of lotteries and casinos?

In other ways, things are back to usual. We certainly still have our quotient of wacky politics. This week, our formerly fugitive clerk of court, Kimberly Williamson Butler (also now a mayoral candidate), revealed that she sees herself as comparable to Rosa Parks, Dr. King, Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela. Perhaps more astonishing than her immodesty was the group of people of mixed race there to applaud her as she came out of prison. And most of the schizophrenic street “characters” who have haunted the French Quarter for years seem to have returned. Indeed, a first-time traveler to the city would probably not notice anything awry or, if he did think the town a bit slovenly and unkempt, would not realize that such is simply its usual condition. He may notice some blue tarps still on the roofs while driving in from the airport through Jefferson Parish, but he would find the French Quarter perfectly intact, as it pretty much was the day after the storm (apart from some trees blown over and debris in the street). Canal Street looks only a bit more dismal than usual. Most out-of-towners coming into my shop admit that their friends told them they were crazy to come down here, as if things were still as wild as during that hectic week after the storm. So now we sit beneath the black cloud of a self-fulfilling prophecy: No tourists will come if others dare not.

A repeat visitor would probably notice some changes, but if he were to stick to the French Quarter, they would not be many. He may be disappointed by the decline of service in the hotels and restaurants, or that one or another of his favorite restaurants might not have reopened or may be keeping odd hours or have a limited menu. Were he to drive uptown, however, he would find the shops on Magazine Street thriving as before with their mostly local business. But the great canopy of oak trees along St. Charles Avenue is now sadly in tatters, the branches looking more like stark antlers than their formerly fulsome, shade-bearing selves. And it is getting hot again, and with the summer comes hurricane season, as inevitably as Mardi Gras follows Twelfth Night. When residents were returning in October, I noticed that many people living here but originally from somewhere else bolted permanently, in fear of just that—another hurricane season. For most of us who are from the area, it is not quite as frightful, kind of in the blood, like the threat of avalanches to mountain-bred people or earthquakes to Californians. We all live beneath the threat of natural catastrophe of some kind or another. What one might hope is not to have to fear the price of human-bred catastrophe quite so frequently. And, by the way, apart from construction supplies, there is one commodity apparently in greater demand now than before the storm. Gun sales are way up.

Leave a Reply