On the fourth floor rotunda of the Oklahoma State Capitol hangs a curious portrait entitled “Carl Albert,” painted in oil by distinguished Sooner State artist Charles Banks Wilson and dedicated in 1977. It depicts the 46th Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. Only 5’4” in real life, Carl Albert (1908-2000) looms large in the foreground in a brown business suit and striped tie. In his watchful eyes and bemused smile, one senses a man of power who means business.

Even without the image of the U.S. Capitol in the background, someone gazing at the portrait might suspect that its subject’s business was politics. And Albert was, in fact, the consummate public servant, the embodiment of political philosopher Willmoore Kendall’s virtuous man of the people. A master of political compromise, Albert was deeply opposed to the unyielding ideological divisions that have all too often paralyzed Congress in recent years. Committed to incremental change and the power of consensus, he rose to the pinnacle of congressional power while never forgetting that his first duty was to the people he represented.

Albert’s humble origins are suggested in Wilson’s painting: Behind and below Albert stand the school children of Bug Tussle, Oklahoma, the town where he grew up. The painting was inspired in part by an old sepia-toned Bug Tussle elementary school photograph that showed Carl as a short boy in the front row. In brilliant color, larger than life, and in the full-flush of political power, the adult Speaker emerges out of the crowd of tiny and anonymous schoolchildren clad in drab overalls and homemade dresses. To the right stands the two-room school with a few Gothic flourishes and small belfry. Above and behind the school is the U.S. Capitol building, but Albert’s image—by its size and vibrancy—dominates everything.

By supersizing his image, the portrait implicitly contrasts Albert’s diminutive physical stature with his enormous reputation. He was, indeed, a “Little Giant,” a nickname he embraced with good humor and not without some justifiable pride.

Albert, who began to dream of becoming a Congressman while still a child, went to Congress in 1947, served as Democratic Whip from 1955 to 1961, House Majority Leader from 1961 to 1971, then Speaker of the House from 1971 until his retirement in 1977. He represented the Third District of Oklahoma, in the southeastern corner of the state.

Culturally akin to the Deep South, this region’s nickname was “Little Dixie” because of the many southerners who migrated there after the defeat of the Confederacy. Like so many American legends, Albert was born in a log cabin, the son of a tenant farmer. The rural poverty of the region is suggested by the attire of the children in the painting; Little Dixie was the poorest part of a poor state.

Wilson’s painting symbolizes the American Dream in which hard work, education, and talent overcome inherited economic and physical limitations, for Albert had methodically worked and educated himself out of the cotton fields. No doubt this background played a role in his becoming an avid New Deal/Fair Deal/Great Society Democrat who believed federal economic intervention was necessary to lighten the hardships of his constituents.

The ideas of Willmoore Kendall provide a fruitful locus for understanding Albert and the significance of his career. As it happens, Willmoore and Carl were boyhood friends in Oklahoma and roommates at Oxford in the 1930s. In his three decades representing Oklahoma’s Third District, Albert embodied the ideal of a democratic leader as understood by Kendall and, more distantly, as elucidated by Aristotle. He almost perfectly fit the mold of Kendall’s democratic “best man,” beloved by his constituents and representing his district’s particular interests in Washington. Like Kendall, Albert believed that having a variety of viewpoints and interests in Congress was an asset to democracy. He distrusted purely ideological partisan divisions and believed that Congress, particularly the House, should reflect the diversity of the United States.

Albert was also an extremely adept practitioner of those acts of legislative deliberation that Kendall saw as lying at the heart of American democracy. In his teaching, Kendall held that Congress was, and should be, the sovereign center of the federal government. Although engaged in actual politics rather than in theory, Albert strongly prized the prerogatives of Congress and battled to uphold them against executive encroachment.

In a series of beautifully-constructed articles written in the 1950s and 1960s, Kendall tweaked Aristotle to teach that “the people, in choosing the representatives who are to exercise the powers granted to office-holders under the Constitution, should seek the ‘best men.’” Local communities should send their highest caliber individuals to Washington to represent their interests and to deliberate carefully with other such persons to promote the general welfare of the United States.

Popularly elected, these representatives exemplified democracy: the rule of the people. However, the representatives were to be uninstructed—that is, not elected to vote certain ways on certain issues, but to use their best judgment in the interests of their district and of the country. Localities, Kendall said, mostly did not and mostly should not vote primarily on issues. Rather they mostly did and mostly should elect persons they considered to be “virtuous men,” the natural aristocrats of their home places.

Such individuals, deeply committed to their home places and well-connected to local business interests, would promote the well-being of their communities more effectively than any distant president ever could. In elections such representatives could talk about “something,” real things that they had done and would do for their district, rather than “nothing,” the vague promises of presidential campaigns.

Thus, thought Kendall, the American system, properly understood, combined the best single feature of democracy, rule by the people, with what Aristotle called the greatest advantage of aristocracy, rule by the best. Should a representative’s views diverge too dramatically from those of his constituents, voters could remove him at the next election. Normally, however, voters would defer to elected officials they knew face-to-face and admired. Leaders elected to Congress in this manner better represented the actual desires of the American people than did fleeting presidential majorities.

Albert exemplified this model. In retirement, he noted how service to his district had won him enough trust among local voters so that he could vote his “convictions” on important issues. From the beginning of his career, he understood that taking care of his “district’s special needs” was vital to his political future. In his fascinating autobiography, Little Giant: The Life and Times of Speaker Carl Albert (1999), Albert recounts many mundane achievements, among them preserving Oklahoma’s share of the national peanut quota, intervening with the Marines to enable the sole surviving son of a poor constituent to avoid combat, and promoting rural electrification and flood control. He wrote:

Because the Third District’s voters knew and trusted me, they let me build a career of service. They knew that that career was more important than any vote I ever cast because they knew that my service embraced the best of their beliefs and the greatest of their needs.

Reading some accounts of his career, including his own, one might think of Albert as a consistent liberal dedicated to Civil Rights and solidly pro-labor. However, this impression would be misleading. In his autobiography, for example, Albert calls the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 “viciously antilabor” but fails to mention that he voted to override President Truman’s veto of the act. In the same year he joined the majority when the House voted to ban the poll tax, and a decade later voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Albert was not always consistent, nor altogether candid in retrospect. If he had always cherished “the civil rights of all people,” as he claims in Little Giant, he compromised these principles early in his career to avoid antagonizing his constituents. Later Albert became more visibly liberal, providing great assistance to President Johnson, for example, in securing passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Having earned the trust of Third District voters, he now felt secure enough to lead them in what he had always known (or claims to have known) was the right direction.

Throughout his career, Albert believed that an “active state, promoting equal opportunity…could enhance the status of all Americans.” Far from being hostile to business, however, he believed New Deal-style liberalism had “saved capitalism.” Like most Congressmen, he was well-connected to local business concerns: Oklahoma coal-mining, petroleum, and mercantile interests funded his career. Nevertheless, qua Kendall, Albert’s ideal was that of the aristocrat (the best man), not the oligarch (the rich man). When he retired as Speaker, Albert declined lucrative offers to lobby “old friends in Congress” because “Ernie Albert’s boy was not for sale.”

Throughout his career, Albert believed that an “active state, promoting equal opportunity…could enhance the status of all Americans.” Far from being hostile to business, however, he believed New Deal-style liberalism had “saved capitalism.” Like most Congressmen, he was well-connected to local business concerns: Oklahoma coal-mining, petroleum, and mercantile interests funded his career. Nevertheless, qua Kendall, Albert’s ideal was that of the aristocrat (the best man), not the oligarch (the rich man). When he retired as Speaker, Albert declined lucrative offers to lobby “old friends in Congress” because “Ernie Albert’s boy was not for sale.”

Instead, like Odysseus returning to Ithaca, Albert returned to Bug Tussle. Sitting on his porch after a long and successful career, he looked out over the gigantic manmade Lake Eufaula, funding for which Albert had shepherded through Congress.

For much of the 20th century, the leading thinkers of political science criticized the politics of compromise that Albert practiced so well, and called for programmatic competition between ideologically distinct political parties. Such scholars believed that sharp partisanship in Congress would strengthen democracy by giving voters a clear-cut choice between distinct political alternatives. Elected officials would possess clear mandates to enact voters’ wishes.

Kendall strongly disagreed with this consensus, arguing that the nebulous nature of American party divisions promoted social and political stability. Ideological overlap and shared interests between the parties made give-and-take possible in Congress. Painstaking negotiations between various local interests within and between parties, Kendall argued, made it feasible to eke out win-win political deals. Such compromises often left one party, or party faction, disappointed but not humiliated. If parties became ideologically consistent and party divisions grew sharper, he believed compromise would be more difficult. Congressional votes would become straight-up win or lose situations.

In similar fashion, Albert resented the efforts of the most liberal members of his own party to “define the canon of Democratic orthodoxy.” Sometimes he complained of being trapped in a crossfire between “unreconstructed Dixiecrats” and “far out liberals” who wanted to “put him in a cage.” Rather than institute a program based on the party’s presidential platform, Albert thought the job of House and Senate leaders “was to cultivate winning majorities in the two houses of Congress.”

Albert realized that, even within his own party, he had to balance numerous interests, for each member of the House represented a unique district. Some were urban and liberal, others rural and conservative. Some seats were safe, some vulnerable. Like Kendall he understood congressional elections as 435 separate contests. Kendall had argued that these districts were composed of distinctly structured communities, each with different sets of voters, interests, and leaders. Albert learned the same lesson in political service.

Albert never forgot that the political diversity of his own party—and of America—was reflected in Congress. Early on, he had cozied up to Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and House Majority Leader John McCormack. Rayburn, a Texas Baptist from Fannin County, represented a rural district just across the Red River from Albert’s own. McCormack, a Catholic from blue-collar South Boston, spoke for a different set of constituents. These elder statesmen became mentors for Albert because they recognized his intelligence and work ethic. With their encouragement, Albert dedicated himself to a House career. Left-wing Democrats distrusted him as too conservative and too southern. He disliked them in turn for claiming that most sitting members of the party in Congress were not real Democrats.

Yet one might not wish such divisions away, and Albert understood that he had to work “with what Congress in fact was.” He did in real life what Kendall commended in theory: He sought incremental change in Congress through deliberation aimed at consensus. Kendall argued that railroading through major political changes, even beneficial changes, via judicial ruling, presidential fiat, or bare legislative majorities, could lead to a long-lasting backlash he called “irredentism.” Albert also feared that disciplining “our largest single element [southern representatives]” might cause “permanent estrangement.” He understood with Kendall that congressional give and take among diverse interests, within and between parties, was vital for the well-being of the American political system.

In breaking the Southern stranglehold over legislation, Albert achieved real changes through careful negotiation. In early 1961, Speaker Rayburn, with Albert at his side, rejected demands by President Kennedy to break Southern power on the House Rules Committee. The White House, said Rayburn, had “no business at all” interfering with internal Congressional processes. Albert and Rayburn then hammered out a compromise by adding new members to the committee. Behind the scenes negotiations among congressional representatives themselves—facilitated by Rayburn, McCormack, and Albert—achieved the desired result. Administration efforts to sway votes, said Albert, attained nothing, and while the House itself had lessened the power of the committee, the compromise caused “no permanent division into embittered Southern and anti-Southern elements.”

In breaking the Southern stranglehold over legislation, Albert achieved real changes through careful negotiation. In early 1961, Speaker Rayburn, with Albert at his side, rejected demands by President Kennedy to break Southern power on the House Rules Committee. The White House, said Rayburn, had “no business at all” interfering with internal Congressional processes. Albert and Rayburn then hammered out a compromise by adding new members to the committee. Behind the scenes negotiations among congressional representatives themselves—facilitated by Rayburn, McCormack, and Albert—achieved the desired result. Administration efforts to sway votes, said Albert, attained nothing, and while the House itself had lessened the power of the committee, the compromise caused “no permanent division into embittered Southern and anti-Southern elements.”

Throughout his career, Albert remained devoted to maintaining the power and dignity of Congress. As he writes in Little Giant, he “loved the House of Representatives” and reveled in its history. As a young Congressman, in good Aristotelean fashion, Albert put on the virtuous “House Habit” of hard work, deliberation and consensus building. In 1965 he took pride that reforms to the Ways and Means Committee—which in turn facilitated passage of many Great Society programs—had been “entirely conceived and executed by the House leadership.” Pushing through a budget measure in 1973, Albert faced down President Nixon so that federal budgeting “would rest firmly where the Founding Fathers had placed it,” that is, in Congress. In 1973 he moved forward the House’s most powerful constitutional weapon by authorizing an impeachment inquiry against Nixon. After retirement, Albert took pride in the fact that the Carl Albert Congressional Research Center was the “only academic facility in America devoted to the study of its legislative branch.”

Although a committed Democrat, Albert valued working across the aisle. He cherished friendships with Republican Congressional leaders Joseph Martin and Gerald Ford. During the Eisenhower administration, Albert, as part of the Democratic leadership, helped the President pass legislation that Congressional Republicans opposed.

On other occasions, faced with recalcitrance in his own party on important legislation, Albert knew how to turn nimbly to House Republicans. In 1964, for example, he worked out a deal with Minority Leader Charles Halleck to push through the Civil Rights Act. Most famously, for several months in 1973 after Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation, Albert stood next in line to the presidency but, even amidst Watergate, played no games. He urged the president to nominate House Republican Gerald Ford and worked to assure Ford’s quick confirmation.

Kendall died before Albert became Speaker of the House, but he admired the achievements of his former Oxford roommate and wanted to see him “in that Speaker’s chair.” The men’s views on politics often diverged significantly. Albert remained more deferential to the federal courts than Kendall thought wise, and Kendall valued the arcane House procedures that Albert dismantled.

But in their shared disapproval of ideologically pure parties, their conviction that legislative deliberation was the key to good governance, and their insistence upon the sovereignty of congressional power, Carl and Willmoore thought alike. Kendall understood that his old friend had become the best man of Bug Tussle and that his career exemplified the healthiest aspects of American democracy.

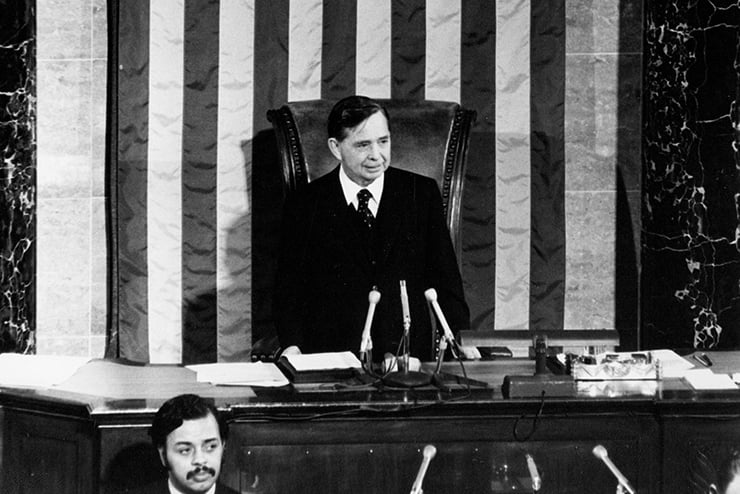

Image Credit:

Carl Albert standing at his desk in the congressional chamber (Carl Albert Research and Studies Center, Congressional Collection)

Leave a Reply