This year marks the centennial of the publication of Owen Wister’s Lady Baltimore, a comedy of manners about a wedding cake. Or, rather, it is about an honorable young Charlestonian’s determination to keep faith with a decidedly dishonorable young woman whom he has, in a moment of fatal infatuation, promised to marry—thus, the necessity of the cake from whence the novel takes its name. The novel sold well enough to become one of the best sellers of 1906 and was warmly praised by the likes of Henry James and Edith Wharton. For several decades, Wister’s witty tale of honor and deception received a generally favorable critical reception, but its critical fortunes declined precipitously after Wister’s death in 1938. Since the 1960’s, the scant attention paid to Lady Baltimore has focused on its racial politics, to the neglect of the novel as a whole.

This is, indeed, a sorry state of affairs. Even here in Charleston, the city celebrated so lovingly in the novel’s pages, Lady Baltimore seems to be the subject of a discreet silence. For some time, I was puzzled by this, for the novel has lost little if any of its original charm. While DuBose Heyward’s sentimental Porgy is daily fodder for every horse-and-buggy tour guide on Meeting Street and Pat Conroy (a decidedly inferior writer) is feted at Spoleto soirées, Wister and his Lady seem to arouse only embarrassment. Wister’s fault, it seems, is twofold: First, his treatment of racial politics a century ago falls well short of anything that might qualify for Oprah’s Book Club today. Second, his narrator is unabashedly elitist in his admiring presentation of an old Charleston aristocracy besieged by egalitarian envy and nouveau riche vulgarity. All of this is exacerbated by another problem. If the outspoken narrator, Augustus, could be seen as just another character, then his views might be more easily (and smugly) dismissed as the pitiable bigotry of a benighted era. But Augustus is too transparently a mouthpiece for the views of Wister himself, and, for the sensitive and progressive modern reader, this presents a perplexing matter of conscience. He begins to feel implicated by the very act of reading; he is, willy-nilly, somehow complicit. Thus the author must be made to shoulder the blame for the reader’s feelings of guilt by association.

I have no intention of exploring here Wister’s views on the race question, except to say that they were very nearly identical to those of his friend, Theodore Roosevelt, and that the views of both men were altogether typical of a period when—in the backwash of a failed Reconstruction—the vast majority of Southerners and Northerners alike seriously doubted whether black Americans would ever be ready for full equality. Far more worthy of our attention is Wister’s exploration of the tensions inherent in the Southern code of honor upheld by the old Charleston aristocracy. For it is upon a matter of honor that the primary plot of Lady Baltimore turns.

Augustus—the scion of a family whose ancestors can be traced to the old colonial stock—is a refugee from the North vacationing in the South who represents himself as one of the new generation of Northerners free of the anti-Southern prejudices of the Civil War generation. In his contempt for the present age, Augustus yearns to recover the spirit of the age that preceded the war, the spirit of the first American nation, the first American family, which was one in North and South. Frustrated not only by the moral hypocrisy of the North but by the vulgar materialism of its nouveau riche, he has come to the South predisposed to find there some remnant of an older, more graceful world. And what he discovers in this “little city of oblivion . . . shut in with its lavender and pressed-rose memories” is a place like “nowhere else in America”—a city whose charm, character, and “true elegance” provide him with a much-needed succor against the “sullen welter of democracy” that afflicts the rest of the country. Having come armed with letters of introduction, he is invited into the parlors of the best old Charleston families, who are very much agitated, he learns, over the impending marriage between John Mayrant, the novel’s hero, and Hortense Rieppe, a young woman whom he met on a trip north to Newport and to whom, with a misguided youthful ardor, he became engaged. Hortense is reputed to be from Georgia (much to the disgust of the Charlestonians) but is now a much sought after habitué of the Northern watering holes of the nouveaux riche. She is, in the words of the old ladies of Charleston, a “steel wasp,” an alluring opportunist. This, Mayrant has come reluctantly to see but feels that, as a gentleman, “he must stand to his word.” In this stubborn refusal, Mayrant stands not only against Augustus, who tries repeatedly to convince John that his sense of honor on this point is a piece of “moral quixotism,” but against the community at large.

Bertram Wyatt-Brown reminds us that the term honor signifies not only an individual but a communal code; it is “a cluster of ethical rules, most readily found in societies of small communities, by which judgments of behavior are ratified by community consensus.” As Mayrant persists in his “folly,” the moral consensus of his tightly knit community hardens around him with increasing disapprobation. Gradually, Augustus comes to recognize the nature of Mayrant’s special importance in this community. He stands at the center of a “circle . . . of interested people”; he is the “jewel” in their “collective sense of possession [of] him, . . . as of an heir to some princely estate, who must be worthy for the sake of the community even before he was worthy for his own sake.” Mayrant is one of the few young men in the circle of the old Charleston elite whose character and breeding is worthy of the antebellum ideal that remains enshrined in their collective memory. Thus, “while he might amuse himself,” he may not “marry outside certain lines prescribed, or depart from his circle’s established creeds, divine and social.”

I have returned to the above quoted lines many times since I first discovered Lady Baltimore, and I am always made uncomfortably aware of how alien, and even offensive, they must seem to almost anyone born, like me, after World War II. Above all, we are affronted by the notion that “character” may require “breeding,” that it cannot be put on like a pair of Hilfiger aviator shades purchased at a discount at our local outlet mall. And what would the average American these days make of the claim that he should be “worthy for the sake of the community”? John Mayrant, however, is tormented by a conflict that places him at odds with a circle of kith and kin whose collective “character” is woven of the same stubborn cloth as his own. Thus, he seeks refuge in a friendship with Augustus, who is surreptitiously determined to persuade the younger man of the error of his ways. But Mayrant insists that, if a man is a gentleman, “he must stand to his word . . . unless [the lady] releases him.”

In every good tale of chivalry, there must be an enchantment. When Hortense Rieppe makes her entrance in the novel’s second half, the power of Mayrant’s original enchantment is clarified. Even the seemingly sexless Augustus is brought, if only for a moment, under her spell. When she first arrives in Charleston with her entourage of nouveaux riche friends from the North (collectively known as “the Replacers”), she is mysteriously veiled. Later, when he looks upon her face, he reflects that “her outward appearance was as shrouded as her inward qualities.” When she speaks (leaving Augustus in an hilarious state of libidinal paralysis), “each slow, schooled syllable” simmers with erotic challenge. But even as Augustus is momentarily intoxicated by the sensual charms of this Georgian Venus, Mayrant (like Tannhauser in Wagner’s opera of that name, frequently alluded to in the novel), encountering Eliza La Heu, the novel’s heroine, in the Woman’s Exchange, falls under the power of another, more spiritualized affection. Beneath the Carolina charm of the vivacious Eliza lies a chaste and patient devotion. Like Tannhauser’s Elizabeth, she possesses a “natural and perfect dignity” that John instantly recognizes. But his promise to the treacherous Hortense prevents him from acting on that recognition.

What most baffles Augustus is why Hortense has not long since broken with Mayrant. If she is the gold-digger that he suspects, then why her continued interest in his apparently impoverished friend? Eventually, he learns that she is motivated, at least in part, by the knowledge that Mayrant will soon be a rich man. She has discovered (with the assistance of one of her Replacer friends) that an apparently worthless phosphate mine that John stands to inherit is actually far from worthless—a fact of which Mayrant himself is as yet unaware. Augustus believes that he has now plumbed the depths of the real Hortense. Her mystery stripped away as the product of cunning artifice, she becomes for him the “perfected specimen of the latest American moment.” And yet, some doubt remains. If Hortense’s opportunism is as purely material as Augustus assumes, why choose Mayrant when she has any number of freshly minted Newport millionaires at her beck and call? Quite by chance, Augustus overhears a whispered conversation that provides him the final revelation: “And now the voice of Hortense sank still deeper in dreaminess,—down to where the truth lay; and from those depths . . . she spoke: ‘I think I want him for his innocence.’”

As Augustus recognizes, what Mayrant arouses in Hortense is a perverse passion, the only sort of “love” that she, in her indifferent sophistication, is able to feel. She and her Replacer friends are suffering from an “ennui [that] gnaws at their vitals.” For Hortense, Mayrant is the treatment for the disease. But Augustus is sure that a day will come when, “having had her taste of John’s innocence,” Hortense will “wax restless for the Replacers, . . . for the prismatic life.” Imagining what such a future might mean for his young friend, the oracular Augustus reflects, “Then it might interest her to corrupt John.”

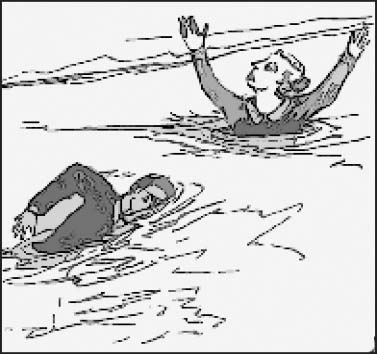

Fortunately for Mayrant, that day never comes. The novel’s providential machinery and his own well-bred moral elegance combine in a moment of poetic justice to yield the solution to his dilemma—the “release” from his hastily plighted promise that his honor requires. When Augustus and Mayrant join the Replacers aboard banker Charlie Bohm’s sumptuously provided yacht for a prenuptial cocktail party, Hortense, on a whim, throws herself fully clothed into the waters of Charleston harbor. This melodramatic display seems to have no other purpose than to gratify her own sense of power over Mayrant; she is confident that the chivalrous boy will dive in after her. But in the event, she fails to realize the danger of the outgoing tide and is swiftly drawn away, struggling to stay afloat. Mayrant, of course, does not hesitate and manages at length to save her life.

Only Augustus is close enough to overhear the words exchanged between his friend and Hortense as Mayrant helps her aboard the yacht: “And so I owe you my life,” says Hortense, softly. “And so I restore it to you complete,” John replies. In the moral economy of this comedy of manners, this amounts to a kind of sacrificial exchange. Mayrant has bound himself to Hortense by an oath that cannot be broken but which can be dissolved, as it were, by a higher moral claim. Having risked his own life to save hers, Mayrant is now free. Hortense has become the debtor; it is now Mayrant who holds the bond, the title to her restored life. To return that life to her “complete” is to dissolve the bond and, thus, the earlier promise of marriage. To her credit, Hortense immediately recognizes the irony, and, for the first time, her mask of indifference slips. Observed only by Augustus, Hortense turns away, and he reads “her face for an instant . . . before the furious hate in it was mastered.”

In this sacrificial exchange, Wister clearly wishes to suggest a broader moral application. In spite of the great crime that was slavery, the South, like Mayrant himself, has, in her long post-bellum suffering and impoverishment, managed to preserve a moral innocence and a grace that the North has lost. This is most evident in Augustus’ repeatedly expressed loathing for the Replacers. They represent for Augustus (and surely for Wister) the antithesis of everything the old Charleston aristocracy stands for. Above all, their natures are warped by an obsessive preoccupation with the economic “angle.” Given a tour of St. Michael’s church, they are blind to its time-hallowed charms. Of banker Charlie Bohm, Augustus notes that

Instinct and long training had given his eye . . . the glance of a Replacer—which plainly calculated “Can this be made worth money to me?” and which died instantly to a glaze of indifference on seeing that no money could be made.

Wister undoubtedly intended the Replacers to be understood as a broadly representative portrayal of the rise of a new American elite. They are repeatedly associated with the decline of social standards at Newport, where self-made millionaires were buying up everything in sight, especially the “family pictures” of the old gentility in a fraudulent effort to authenticate their dubiously achieved social status. The “yellow rich,” as Augustus calls them, are the essence of everything that had gone wrong with America since the triumph of the North. Unlike the old gentility they are replacing, they are devoid of any moral core.

As Stow Persons has argued in The Decline of American Gentility, the displacement of the old gentry class was all but accomplished at the turn of the century. Much of Wister’s concern for the damage wrought by the nouveau riche is confirmed in Persons’ study. He notes that the rise of the economic elite on the Gilded Age tide of industrial and commercial wealth

destroyed the social distinctions which had formerly prevailed, substituting for them a common mercenary standard. . . . In place of the former stability of a society divided into relatively firm social classes there now emerged the restless universal flux of the mass society,

a mass whose values were increasingly shaped by a desire to emulate the new economic elite. It might be argued that Wister’s real motive in writing Lady Baltimore was to reassert the privilege of his own gentry class against an increasingly threatening demos. I would argue, however, that any attempt to dismiss the novel as a reactionary interlude in the long march of the masses toward an imagined egalitarian paradise will fall short of the mark. Perhaps we would prefer to believe that social elites are by definition pernicious and that political progress will eventually eliminate them. But history and common sense suggest that we are mistaken, that the formation of elites may be, in fact, a constant in human societies. And if that is so, then the most fundamental political question involves judgments about the quality of those elites.

In spite of Augustus’ occasional flashes of historical pessimism in Lady Baltimore, Wister himself was hopeful that the tidal wave of moral corruption that he saw inundating the Old Republic would recede in time. He clearly intended to offer in his hero, Mayrant, a model for the formation of a new elite bred in part out of the old gentry stock. In the final chapter in the novel, Augustus visits the now-married John Mayrant and Eliza La Heu. He reflects that it was once his

good fortune to make [Eliza] see that there is on our soil nowadays such a being as an American, who feels, wherever he goes in our native land, that it is all his and that he belongs everywhere to it.

While Wister’s dream of the restoration of the values of the Old Republic has, lamentably, gone unrealized, his optimism about a reunion of Yankee Doodle and Dixie has, ironically, been more than vindicated, though in a manner that he would have deplored. Dixie is no less enamored these days of the “economic angle” than is Yankee Doodle. And here in Charleston—called the Holy City because so many martyrs to the cause of independence lie buried here—the Replacers have come at last to roost. Back in 1906, when Lady Baltimore was hot off the presses, it was reviewed by the editor of the Charleston News and Courier, J.C. Hemphill, who wrote that Wister was “distinctly cruel” in depicting Charleston as “a sepulcher of memories and not a living, breathing reality of commercial times.” Hemphill, who was a great booster of the failed Charleston Exposition of 1902, would be delighted in the shallows of his Masonic soul to see what Charleston has become. Million-dollar condominiums sprout like toadstools on what was once sacred ground, driving up property taxes and driving out Charlestonians who have lived on the peninsula for generations. While tens of thousands of tourists flock to the city annually for a taste of her Old World charm, stuffing their Gap tote bags with gewgaws manufactured by Chinese capitalists, the Hon. Joseph Riley, longest-serving mayor in America, lusts in his Irish heart to incorporate neighboring James Island, whose residents are (God bless them) resisting mightily. In 1930, Wister wrote, in his Roosevelt: The Story of a Friendship, that the Charleston he had come to love in his many visits to the city was “an oasis in our great American desert of mongrel din and waste.” He praised this last redoubt of the first American nation as a place of enchantment “unmocked by the present.” He was captivated by a generation of Charlestonians who dwelt here “amid this visible fragrance of time . . . in much quiet, with an entire . . . aversion to show.” Today, I am afraid, Wister’s quiet oasis has been all but obliterated by the mongrel din.

Leave a Reply