For as long as young Villem could remember, hunkeys had occupied the lowest rung in Punxsutawney’s social pecking order. The Italians had their various business enterprises; the Irish had their legions of bishops, monsignors, and priests; and the Slavs were miners known by the pejorative hunkey. Vil’s father, Juraj Oddany, dug coal, as did two older brothers who quit school after the eighth grade to help feed the family’s 14 mouths. It was a hard life—physically demanding, yet a far cry from the old country’s coercive Magyarization. Life in America was full of simple pleasures—like the Slovak Club on Number Five Hill, with its fine wood bar and shuffleboard in the basement; groundhog hunts; and baseball.

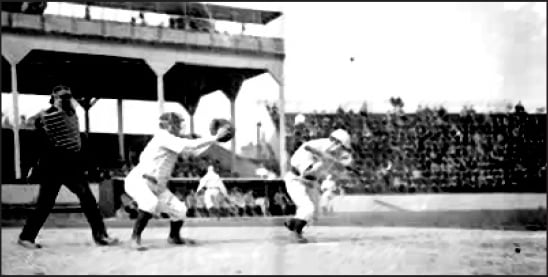

The story of how Vil came to play for the townie team, the Punxy Electrics, is brief. He and his friends spent their summers playing pickup games in a grassy lot on Five, calling themselves the Aggies. It was tradition in the small mining towns of Western Pennsylvania for the mine super to offer a job to a family if a son was skilled at baseball. Vil was just another “dumb hunkey” to the townies. But he was a good ballplayer, and that was good enough for the Electrics, a team with its own legacy to defend. In the mid-1930’s, the Electrics defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates, a major-league team whose roster featured Paul “Big Poison” and Lloyd “Little Poison” Waner, both of whom would later be enshrined at Cooperstown. The Slovak Club’s Old Slavs chalked it up to the Pirates underestimating the effects of the slivovitza served at the pregame banquet on Mahoning Street. Townies insisted it was “local talent.” Whatever the cause, the Pirates, egos bruised, were seeking a rematch. This game would be played at Punxy’s Main Field under the lights.

The circumstances surrounding Vil’s entry into the Slavic League are more complicated. Vil thought it ridiculous to name a baseball team for buccaneers wearing eyepatches. He was a Detroit Tigers fan, through and through. Vil prided himself on his “Tiger eye.” He was a right-handed, spray-hitting shortstop known among opposing pitchers as “hard to pitch around.” Some tried to intimidate him. Vil, to their chagrin, always responded by digging in deeper, and closer, to the plate.

Vil bore insults quietly, secure in the knowledge that he, not the pitchers, won most of these duels. Dueling continued off the field, the physical assaults changing with the seasons. In winter and early spring, it was snowballs and chunks of ice. Easter produced a truce. In summer and fall, it was coke from the beehives (small ovens) that dotted Punxy’s woods. The play was always hit-and-run: the verbal insult (“dumb hunkey”) followed by the attempted physical assault and, finally, flight. As his tormentors fled, Vil thought of the groundhogs the Oddany men dispatched with the family rifle. Then he paused, crossed himself, and recalled the Old Slavs’ adage: “It’s hard to keep a good hunkey down when he gets up after ducking!” Vil, like his ancestors, had learned this lesson a long time ago.

It came to pass that the Pirates got their rematch, and, in the bottom of the ninth, they led the Electrics, who had two on and two out, 5-4. The Slovak Club’s Old Slavs still argue over what transpired next. Some contend that Fuzzy Terwilliger, the Electrics’ top hitter, did not see the splinter before he sat on the dugout bench after the eighth inning. Others insist Terwilliger was just plain cowardly, having struck out at his last three at-bats. Yet others saw Providence in Electrics manager Seamus Martini’s decision to pinch-hit Young Vil, the team’s only Slav, with the game—and town honor—hanging in the balance. It should not be forgotten that skeptics of this final theory will note that Martini had already played the entire team and had no one else to send to the plate in Terwilliger’s place.

Vil was barely 18, and, as he stepped up to the plate, many unfriendly eyes focused on him. His father and older brothers were working the night shift. His mother and sisters, as hard as they had tried, never understood the mathematical intricacies of the game. Of course, his younger brothers, Jahnko and Tomas, were no doubt praying for him in the bleachers instead of playing stickball in the lighted parking lot across from Ss. Cosmas and Damian. Vil dug in as the hecklers screamed, “Dumb hunkey!”

There is unanimity of opinion about what transpired next. Vil later insisted he was nervous, being the youngest on the team. Besides, he was not used to playing under Main Field’s lights. The Old Slavs knew better. Martika Krivosky waved, and Vil, for once, forgot to duck. The Pirates’ pitcher snickered; the catcher feigned sympathy; the women, led by Martika Krivosky, cried; and the parish priest was summoned to administer the Sacrament of Extreme Unction. Vil’s body lay motionless in the chalk. His soul hovered above home plate, and he felt his life passing away. Suddenly, a figure appeared. At first, he thought it might be Saint Peter. But the first Pope had never worn the Detroit Tigers’ Olde English D. Why, it was Barney McCosky, Vil thought—the young, left-hitting Detroit outfielder from Coal Run, Pennsylvania, who hit .340 with 200 hits and 19 triples the previous year when the Tigers won the American League. Other ballplayers stood in the shadows, and Vil heard Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, and other Slavic tongues, including Slovak, spoken.

“You have to watch those curves if you want to play in the Slavic League,” said a voice from the shadows.

There was laughter. “Never mind them,” Barney McCosky told Vil. “It’s not your time.” He spoke with conviction. “We’ll be waiting for you when it is.” The crowd fell silent as Vil picked himself up to face the Pirates, knowing for the first time in his young life that his team was bigger than any nine from Punxy or Pittsburgh.

The Irish and Italians inside local establishments like Grazier’s and Del-a-Monte’s still talk about Young Vil’s clutch hit that spring night, as do the Slovak Club’s Old Slavs when they meet to throw down a slivovitza.

It’s hard to keep a good Slav down.

Leave a Reply