A nine-year-old boy has caused the simmering tension between Western Europeans and Muslim immigrants to boil over once again. This latest incident has occurred in the Netherlands, which over the past decade has become the poster child for failed Muslim integration.

A boy named Yunus, born in the Netherlands to Turkish-Muslim immigrant parents, lives in foster care with a lesbian couple in The Hague. This has infuriated Turkish Muslims both in Turkey and in Europe and has caused a major diplomatic row between the Dutch and Turkish governments.

The story of how Yunus ended up in foster care is fairly complicated. The case went through Dutch family court four different times. It all started in 2004 when Yunus was four months old. He was admitted to the hospital with a broken arm and bruised head. Doctors believed he may have been abused, so he and his two older brothers were moved to foster care. Yunus was placed with a lesbian couple, with whom he remains to this day. The legal complications stem from the fact that Yunus’s situation was not fully investigated in 2004. Experts who subsequently reviewed his medical files disagree on whether he was abused.

In 2007, the court ruled that the two older boys could go home but that further inquiry was needed before a decision could be made about Yunus. His parents did not cooperate with the inquiry. In 2008, the court ordered Yunus’s two brothers back to foster care after receiving reports that they were being abused, but the two boys were spirited away to live with grandparents in Turkey before social workers could fetch them. As a result, the court stripped the parents of their legal parental authority over Yunus in 2011.

In 2013, Yunus’s mother began a media campaign to get her son back, calling on Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to help her. She appeared on a conservative TV station popular with Erdogan’s supporters, wearing a black headscarf and crying hysterically, “How would you feel if your child were living with a lesbian?” Her interview was played again and again, with the TV station calling on viewers to express their outrage via Twitter using the hashtag #stopabusingchildrenholland. Yunus and his two foster mothers went into hiding after receiving threats.

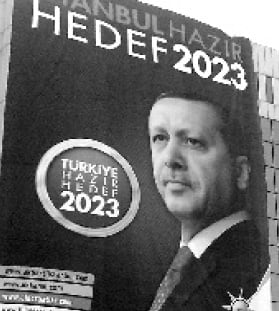

The controversy peaked in March of this year when Erdogan paid an official visit to the Netherlands to celebrate 400 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries. At several of his stops, he was met by protestors calling on him to “rescue” Yunus. His visit to the city of Rotterdam was canceled when Turkish Muslims organized a particularly large protest there.

During his visit, Erdogan called on the Dutch government to inform their Turkish counterparts when children with Turkish citizenship are placed in foster care. The two governments, he argued, should work together to find the right homes for those children. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte responded in no uncertain terms that decisions about foster care are made by Dutch authorities alone. Such a blunt public exchange was very unusual for the mild-mannered Rutte.

Many factors contribute to the failures of Muslim integration in Western Europe, but there are two in particular that caused the Yunus case to become so contentious. The first is that the concept of foster care largely does not exist in Turkey. The second is that the Turkish government sees an important role for itself in the lives of its citizens abroad—even when those citizens gain dual citizenship in another country.

Yunus is the most well-known case, but Turks have been angry about Western European foster care for a long time. In Turkish culture, when parents are unable to care for a child, other family members step in. The way Yunus’s two older brothers were placed with grandparents is typical for Turkey. In Istanbul, a city of 17 million people, there are about 130 foster families. In the Netherlands, a country of 16 million people, there are over 14,000 foster families.

Many Turks regard foster care as a subversive way to assimilate Muslim children and rob them of their faith and cultural identity. Months before Yunus’s case gained the spotlight, the Turkish government announced a plan to “rescue” Turkish children who are placed in non-Muslim foster homes.

Turks tend to speak about the dangers of “Christian and homosexual foster homes” in one breath, or they just lump the two together as “Dutch foster homes.” This is paradoxical since many Christian parents would be just as upset as Yunus’s mother at having their children raised by a homosexual couple. However, Dutch Christians have been largely silent about Yunus’s situation because they are unlikely to encounter it themselves.

The Christian community in the Netherlands has a strong tradition of foster care. “There are many Christian foster families in the Netherlands because of the Christian belief in caring for your neighbor,” says Jan van Benthem, editor of Nederlands Dagblad, a Christian newspaper. “When Christian children in the Netherlands are placed in foster care, they are placed in Christian homes. Perhaps children from orthodox homes might be placed in slightly less orthodox homes, but that’s it.”

In an interview on Dutch TV, Lara Willems, a Dutch social worker and a Muslim, said Muslims are less likely to report abuse in their community because they fear the child will then be placed in a non-Muslim home. “Ultimately, we are Muslims. We believe in God, and we have to answer to God if a child is placed in a non-Muslim home.”

As outrage over Yunus’s foster placement grew, the Dutch child-welfare authority defended itself by pointing out how few Muslims register as foster parents in the Netherlands. The authority said social workers do their best to place children in foster homes that match their religious and cultural backgrounds, but this is not always possible. Consequently, many more Muslims families have now stepped forward and applied to become foster parents. Most Dutch see this as the best solution to the problem.

However, Dutch-Turkish writer Özcan Akyol, a vocal critic of Turkish failure to integrate, does not believe large numbers of Turkish families will become regular foster parents. “We’re now talking about dozens of people, and I don’t think that group will grow in the long term,” he told a Dutch TV news documentary.

Right now, it’s about making a statement. They want to rescue Yunus from his supposedly evil foster parents. But I’m sure that a year down the line, if you look at the number of foster families that have been added, it won’t be more than there are now.

Moreover, Willems, the Dutch Muslim social worker, argues that the problem goes deeper than just a lack of Muslim foster homes. She believes cultural misunderstandings between Dutch social workers and Muslim parents can lead to children being unnecessarily placed in foster care. To avoid such misunderstandings, she argues, the Dutch government should hire more Muslim social workers.

Perhaps having Muslim social workers handle Muslim families will alleviate some of the current tension. But it does little to integrate Muslims into Dutch society.

The second factor that caused Yunus’s foster home to become an international controversy was the Turkish government’s meddling. Erdogan is anxious to portray himself as a strong leader and his country as a major power. The Turkish government sees itself as responsible for the welfare of its citizens abroad. Or, less benevolently (as some critics argue), Turkey sees her emigrants as colonists, establishing foreign outposts for the benefit of the mother country.

The Turkish government has little interest in seeing its citizens integrate into Western European countries and even actively discourages them from doing so. Erdogan, prime minister since 2003, has made it his mission to keep Turks living abroad connected to their homeland.

In 2008, in a speech in Cologne, Germany, to an audience of over 10,000 Turkish emigrants, Erdogan declared that “Assimilation is a crime against human nature . . . Our children must learn German, but they must learn Turkish first.” The speech was delivered in Turkish, and no authorized German translation was released.

The Netherlands allows dual citizenship, and most Dutch Turks, including Yunus, take advantage of this. Some Dutch politicians have argued that abolishing dual citizenship would force immigrants to integrate. But, at least for Turkish immigrants, this is unlikely to make much of a difference. Germany—home to around three million people of Turkish descent—forbids dual citizenship. In response, Erdogan introduced something called a “blue card,” which grants legal privileges to Turks who had to renounce their Turkish citizenship when they gained German citizenship.

Given this history, it is hardly surprising that Erdogan felt comfortable standing next to the Dutch prime minister at a press conference and declaring,

Placing children with homosexual couples does not fit with the values and beliefs of an Islamic people. In Turkey, we would not do that. When this happens, Turkish organizations and institutions must get involved. That is their responsibility. You should not leave this only in the hands of the Dutch government.

Having been firmly rebuffed, Erdogan has signaled his intention to take Yunus’s case and possibly that of other children to the European Court of Human Rights. Thus, Yunus’s situation is far from settled. The people of the Netherlands are facing many questions about the best way to handle foster care for Muslim children—and even more questions about the best way to handle Muslim integration. Yunus will likely be a grown man before any of them are answered.

Leave a Reply