A graph making the rounds on Twitter shows that, since 1970, the share of aggregate national income held by the middle class has plummeted while the share held by the rich has skyrocketed and the share held by the lower class has barely budged. I do not know if this graph has all the particulars right, but its thrust is undoubtedly correct. The decades-long decline of the once-great American middle class is the overarching political reality that the professional conservative movement has spent decades ignoring, obfuscating, and even celebrating.

At about the same time, I came upon an illuminating interview of financial journalist David Gelles by David Leonhardt in The New York Times. Gelles has written a book about the impact of longtime General Electric Chief Executive Jack Welch on the American economy. Welch, who took the reins at GE in 1981, was held up as the model CEO for decades, and many lesser CEOs took their cues accordingly. Welch’s overall approach is neatly summed up in his quip that he wished all GE’s plants were on barges so that he could ship them at a moment’s notice to whatever dismal spot on the planet then had the lowest labor costs. He’d need just enough infrastructure to allow GE to build its goods there and then to bring them back, tariff-free, to sell to Americans.

I never understood the adulation for Welch because I thought what he was doing was, at worst, economic treason and, at best, a renunciation of all the non-economic ties that used to bind companies to communities. As the article noted, Welch “unleashed a wave of mass layoffs and factory closures that other companies followed.”

Before Welch, layoffs were seen as a last resort, a triage measure to save money in a company that was otherwise going to fail. After Welch, layoffs became an accepted way of boosting profits, even at companies that were not in distress. Plants began to close, and jobs got shipped overseas with no concern for anything other than the short-term impact on the bottom line. Most of the profits at GE went to big investors in the form of stock buybacks rather than toward increased wages for workers, improved factories and equipment, or expansion in research and development.

Leonhardt and Gelles concede that Welch made a lot of money for GE investors,

transform[ing] G.E. from an industrial company with a loyal employee base into a corporation that made much of its money from its finance division.… But in the long run, that approach doomed G.E. to failure. The company underinvested in research and development, got hooked on buying other companies to fuel its growth, and its finance division was badly exposed when the financial crisis hit.

Recently, GE announced that it was breaking itself up.

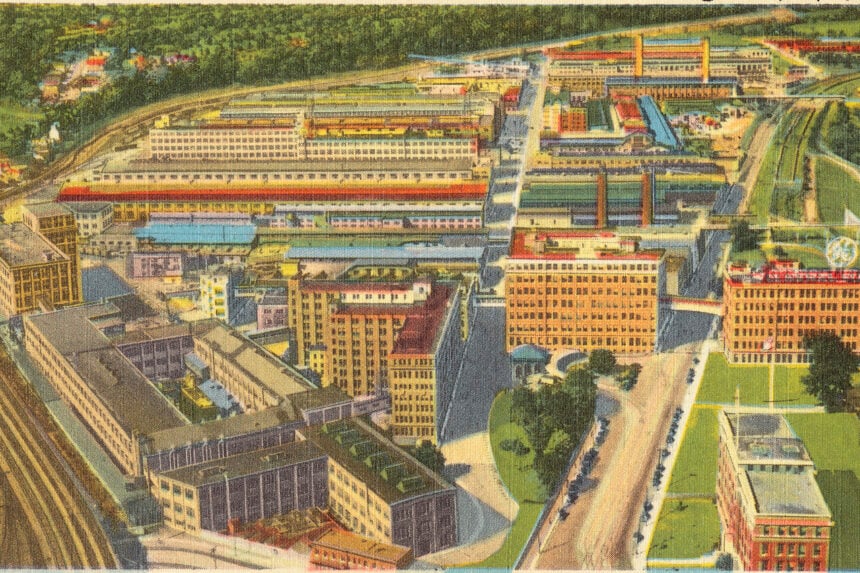

All this really hit home when I recently learned that my Polish great-grandfather and my Polish great-grandmother independently made their first residence in America a boarding house at 529 Westinghouse Avenue, in Schenectady, New York, not 10 years after General Electric had been founded in that city in 1892. Although my great-grandparents did not stay long at that location, many other Polish and Italian immigrants did, and GE brought considerable prosperity both to the European immigrants and to the old-stock Americans who worked for the company in its home city.

As John Cropley wrote in a Nov. 9 article in Schenectady’s Daily Gazette, GE employed up to 45,000 people in Schenectady during World War II, and the company still employed around 25,000 people in the city when Welch took charge. By the time Cropley wrote his article, GE employed only 4,890 workers in all of New York, and there were just 600 union members left doing production work in Schenectady. Not coincidentally, the economic neutron bomb of GE’s failure has left Schenectady, as Cropley describes it, “with a crumbing, deserted downtown, timeworn residential neighborhoods and a population that had plunged by half.”

The same sad story can be told in town after town across America, as the only people who embraced Welchism more eagerly than businessmen looking for quick profits were politicians who told themselves, and us, that dismantling America’s manufacturing base and becoming dependent on hostile, unpredictable foreign countries for everything from weapon parts to baby formula, was somehow a good thing.

Incredibly, against this backdrop, the Biden administration is rolling back some of the tariffs Trump put on Chinese goods. This is madness. We need yet higher tariffs—and quickly—before the long decline of the once-broad American middle class becomes the rapid demise of what remains.

Image: Postcard of General Electric headquarters, Schenectady, NY, circa 1940 (Boston Public Library, via flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Leave a Reply