My wife and I shall visit Paris again this fall, as we have done for years, but the city will be an empty place for us following the death of our dear friend and my revered colleague, Claude Polin, on July 23. Mercifully, Claude was spared the horrors of modern death in a nursing home or a hospital. He died in the early morning with his wife, Nancy, at his side and in the presence of a nurse—in his own bed, at home.

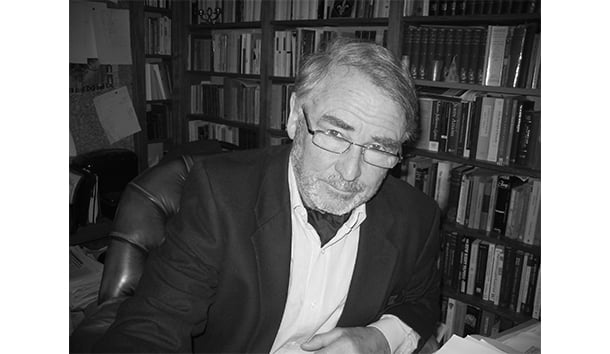

It was, in fact, at home that we usually met him and Nancy for Sunday dinner with the family. Claude preferred to eat his big meal at noon, and Sunday was the convenient day for their daughter Jenny, her husband, Yvon, and their daughters, Marie and Manon, to visit their parents and grandparents. (Tessa, the second daughter, and her family live in Massachusetts, not far from Squam Lake in New Hampshire and the 20-acre island Nancy and her family inherited from her parents, where the Polins spent part of every summer.) We would sit first in the sitting room of the penthouse flat in Rue Rollin, on the Left Bank only a short distance behind the Panthéon, beneath oil portraits of Claude’s ancestors and surrounded by the family antiques to eat hors d’oeuvres before going in to lunch. Early on Sunday mornings Claude would walk to the neighborhood market near Rue Rollin and home again bearing a quantity of the fresh oysters shipped overnight from the northwest coast of France. Nancy is allergic to oysters, and Maureen dislikes them raw, leaving Claude and me to overeat ourselves on the tender pale contents of the knobby blackish-brown shells like small chunks of volcanic rock. On our first lunch at the house, Claude demonstrated for me how an oyster must be eaten. First you slice through the muscle holding the two parts of the shell together. Then you raise the oyster to your teeth. You tilt back your head and aim the end of the shell at your gullet and swallow the clean salt water ahead of the animal itself, which goes down whole in a single gulp, followed by white wine from the tenants’ wine cellar. Much of Claude’s stock was decades old, brought from the family farm south of Paris. On one occasion several years ago, soon after he and his brother had inherited the cellar of their father’s Paris flat, we spent a good half-hour before the ritual of the oysters opening one after the other in a row of dust-caked bottles and sampling their contents. As Claude had foreseen, some of the wines were undrinkable, but most of them were superb. At some point after the meal Claude would invite me into his comfortable small office and offer me the single chair facing his desk. The walls were—they are—crowded with books in several languages pressed tightly into custom bookcases; the single window looks out on the southern side of the Latin Quarter. Here Claude would suggest ideas for the essays he had in mind to write for the next six months or so, and ask for my opinion of them. They were, of course, always excellent. I don’t believe I ever turned down one of these suggestions, or the article that came from it. Last November he suggested tackling the question of whether Marxism is really dead. The result appeared in the June 2018 number of Chronicles. Claude’s second suggestion was a consideration of the essentiality of religion, Christianity in particular, to human society. For some weeks before his death he propped himself in bed while he managed to draft an outline. I should have published it as a final tribute to a great writer, had Nancy not informed me that it was so illegible that, in his condition, even the author had been unable to make head or tail of it.

Three years ago Maureen and I spent a few days with the Polins, their daughters, and several of the grandchildren at their rustic island home. Nancy and I swam, I canoed for the first time in decades, and Claude showed us around the lake, including the island where he and Nancy had been married. He piloted the speedboat with panache—wearing (as I recall) a cap and dark sunglasses—between the channel markers which he seemed to have committed to memory. There is a tennis court on the island, reconstructed and tended by Claude, who was a skilled handyman and accomplished player, as well as a skier. Early each morning I was wakened, as I was as a child, by the cackle of hens tended by Tessa’s three daughters. Claude was already too ill to get around much, but we had good conversations (he sat in his hanging canvas basket chair as we talked) alone before the drinks hour and ate fresh lobster for supper. Before we left the island he signed and presented me with two of his books. They are what one would expect after having read his brilliant columns.

Claude was a royalist and a legitimist who held two degrees from the Sorbonne: agrégé de philosophie and docteur ès lettres, much more difficult than a Ph.D. to earn. Like his father, Raymond Polin, past president of the University of Paris-Sorbonne and a prolific philosopher himself, he was professor emeritus from the same institution. He and Nancy, who comes from an old Boston family, met after she left Smith College and moved to Paris to enroll in the university. For a brief period in his youth Claude was an adherent of the Front National, for which he was scorned for the rest of his life by the French intellectual class. As a man of another, later Resistance he never changed his mind about democracy and the left, and lived (and wrote) for the rest of his life as the proud and lonely lion he was.

Maureen and I knew when we saw him last year that Claude was dying; still we were hoping for a final visit and luncheon (sans huîtres, hélas) with him this November. It was not to be. When I wrote him for the last time to inquire about the religion project and give him the date of our arrival in Paris, I half expected the response I received from Nancy. Claude had died just two days before, and she had been on the point of writing to give me the awful news when my email came through. Sometimes there is something specially terrible about unexpected expected news.

Leave a Reply