I dislike museums, even good ones, and I positively detest the culture warehouses of Paris, London, and New York—the so-called encyclopedic museums, in which I have spent some of the least edifying moments of adult life. I have waited in line, more than once, to get into the Uffizi. I manage to avoid the swarms of gaping Japanese tourists following the magic talisman of the lifted umbrella, only to be trampled upon by herds of half-naked American refugees in their Hard Rock Cafe T-shirts. Rather than abandon hope, I do not enter. Florence is Dante’s city, and it would take a modern Dante to do justice to what his city has become.

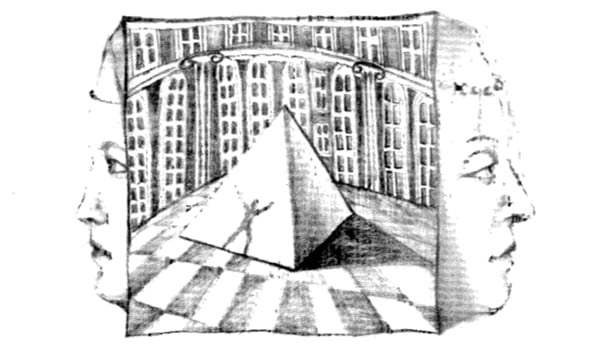

I cannot personally testify to the horrors inside the Uffizi, but I have trudged wearily, from picture to famous picture, through the Louvre. Someone—I assume it is the Marxist minister of culture. Jack Lang—conceived the brilliant idea of forcing visitors to enter through Pei’s ugly and discordant glass pyramid—a Chinese middle finger stuck in the face of European civilization. The real excitement of the Louvre is the stampede of children and tour groups running at breakneck speed to see some masterpiece rumored to be only a halfmile away. I am surprised they do not provide golf carts: perhaps these do not go fast enough.

A poor hick like me waits all his life to sec the Winged Victory or the Venus ofMelos, and when he gets there, all he can think of is how to find Barnum’s famous exhibit marked “Egress.” The Japanese are everywhere, snapping pictures in front of the “No Flash Photos” sign. When I point this out to a Frenchman, he observes that they probably do not speak French. He is right. The Japanese swarm all over Europe trying out their impossible English on Italian train conductors and French waiters. In their behavior, Japanese tourists are worse than the Germans, worse even than the Americans, and I wonder that the governments of these nations are willing to send these ambassadors of ill will and bad taste abroad.

There are many great museums I have not yet visited, but I am willing to bet that the worst spot in any of them is the Sistine Chapel. First-time visitors are always given the same advice by their more experienced friends: go fairly early and make a beeline to the Sistine Chapel—do not even so much as glance at the various collections of sculpture and artifacts along the way. Unfortunately, the same advice is given in all the guidebooks that promise 15 European cities in two weeks on $50 a day, and when you get to the Chapel, it is more like a high school gymnasium during the state finals. You cannot see for all the noise.

Earlier in this century a noted reactionary declared that the only way to save civilization was to ban tourists. Note, he did not say visitors, but tourists, people making an obligatory round of visits according to someone else’s plan. There are, of course, tours and tours. Archeological sites in Sicily or Greece are more accessible to specialized tour groups, but most tours offer a McDonald’s approach to travel: the same bland experience reduplicated millions of times for people too busy to notice what they are consuming.

One of my Italian friends told me that tourists have occasionally sued a travel agency, claiming they never saw the Leaning Tower or St. Mark’s, but tour operators have come up with the solution: a list of notable attractions to be signed at the end of the day by each weary pilgrim. Why do they go? The footsore group sprawled at the foot of the Spanish Steps looks about as happy as 13-year-old boys at their first dance. “Am I having a good time yet?”

Americans always assume they are being cheated by crooked foreigners. Usually the problem is language, since many of our fellow countrymen speak no written language. “The Frogs and Dagos always cheat you,” they say, expressing a contempt that almost justifies the swindles. Serving tourists is not an easy business. The profit margin is low, and the usual recipe for success—good food and service—does not apply to grazing animals on a cattle drive. The French do not believe the customer is always right—a petty and servile notion, beneath the dignity of a man who owns his own business—but their own standard—the best, whether the customer wants it or not— gives wav to “Head’em up, move ’em out” when large groups of one-time visitors are involved.

I remember sitting outdoors in a pleasant trattoria in Lucca. The food was good, the service a bit slow but friendly. Inside, however, a German horde was being whipped through identical courses, while the guide got into a shouting match with the proprietor. I can only assume that the Germans took home mixed memories of Lucca. When I have compared notes with friends who have taken tours, I am always surprised by how disgruntled they arc by bad service, poor food, and a general sense of disorientation. Of course they are disoriented, when they are being processed by an impersonal machine that stamps each diverse individual into the same mold.

Our lives are our own, and any grown-up who is not an invalid ought to be prepared to find his own way through a foreign city. Getting lost is half the experience, as I kept telling my daughter in London, where we wandered lost for hours, only to be washed up on the shore of Buckingham Palace. When you know exactly where you are on the map and can check to see if the guidebook description matches what is in front of you, it is someone else’s perception, not yours. Out of ignorance and ineptitude, I have often found myself wondering at the beauties of some undiscovered church, only to find, back in the hotel, that it is celebrated in the Guide Bleu. In Rome, I stumbled onto Santa Maria Maggiore in search of a drugstore and pecked into San Luigi for the first time because the pizzeria was not open vet.

I am probably misleading my readers into thinking that I play everything by ear. On the contrary, I bore my wife and children, months before a trip, reading histories and guidebooks, studying maps and city plans. Like Henry Reed, I have pored over “A Map of Verona”:

And over this city for a whole long winter season.

Through streets on a map, my thoughts have

hovered and paced.

But these are private and personal preparations, like language study, and guidebooks are the dictionaries and grammars of travel: useful for study in advance and for checking points, but as impractical for conversation with places as with people. Ultimately, your goal is to break free and see things for yourself.

This is truer of museums than of cities. I cannot say how many times I have been standing alone in a room at Chicago’s Art Institute or the National Gallery in Washington, only to be set upon by a train of trouser-clad housewives, each carrying a folding chair. Their lector marches them right in front of the very picture I am looking at and proceeds to deliver a discourse that is half platitude and more than half error (platitudes are sometimes wrong). These women arc not little maids from school; they are battle-hardened veterans of marriage and motherhood. Can’t they look, with their own eyes, at a picture? And if they cannot, what are they doing in a museum?

It is better to be an ignoramus on your own terms than the parrot of a half-trained semi-professional. (I am not, of course, speaking of the excellent guides who give tours of manor houses, palaces, and special collections that are as useful to the art historian as to the school girl, but of the pre-chewed pap spat into the mouths of tour-takers.)

The mischief of arts education began in the 18th century, when it was no longer enough to cultivate an appreciation for the beautiful. Great museums were established to serve as educational institutions inculcating lofty principles. In his will that conferred the original core of the British Museum, Dr. Hans Sloane declared that his collection should be open to the public “for the improvement of the Arts and Sciences and the benefit of mankind.” But it was the Germans, following Winekelmann’s lead, who most insisted upon rational and scientific display of art—first the ancients and only later the moderns—for instructional purposes.

Earlier collections had been assembled haphazardly by kings, noblemen, and princes of the Church to gratify their tastes and impress their friends, but increasingly museums became national foundations, arranged on a scientific basis, for the edification of the populace, and what could possibly be more edifying than a demonstration of the power and glory of the nation and its rulers?

The Louvre, which had been a royal palace before the Revolution, was turned into a grisly display of art treasures that had been looted from the homes of murdered aristocrats. As the armies of the Republic and of the Empire ravaged their way across Europe, the masterpieces of half the world were carted off to France as spoils of war and put on display in the Palais du Louvre, renamed the Museum National and, in 1803, the Musee Napoleon.

After Waterloo, the liberated provinces of Napoleon’s Empire recovered much of the loot, but some of the works of art went not to the original owners but to the royal, papal, and national art museums that were being established or reorganized. The museum became the symbol of nationhood and empire, and the imperial nations of the French, the Germans, and the British displayed their trophies of ancient art—much of it looted from sites in Greece, Turkey, Egypt, and Italy—as proof of their own status as successors to the Roman Empire. One of the first acts of newly independent Greece was to demand the Elgin Marbles back. Those demands have been repeated throughout the years, but Britain retains just enough imperial spirit (or is it spite?) to refuse.

Americans, for obvious reasons, were somewhat slow in founding great museums. The earlier foundations tended to resemble the Charleston Library Society’s collection of curios that constituted the first museum in America (1773). So long as America remained a republic, its museums were very modest affairs and not merely because of the difficulties and the expense of importing art. Our plain republican ancestors were, for the most part, fully employed in building their own civilization on classical models. Let the Europeans worship their ancestors. Our aristocrats were investing their energies into descendants. The connoisseurs among them were gentleman dilettantes who did not confound private taste with public good.

One of the first American promoters of connoisseurship, James Jackson Jarves, was also a collector who called for the creation of public art museums in which “a mental and artistic history of the world may be spread out like a chart before the student.” Jarves’s The Art-Idea was published in 1864, on the eve of the nation’s metamorphosis from republic into empire, and, “by the time of his death in 1888 [as Karl Meyer notes in The Art Museum: Power, Money, Ethics], he had witnessed the first-fruits of his art-idea: a half dozen new art museums, most of them open without an admission fee, each of them determined to rival the Louvre in the scope of its collection.”

The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the greatest of American museums, was established only five years after the war. The founders were—appropriately enough—members of the Union League, but the Museum’s greatest benefactor was J. Pierpont Morgan, the living embodiment of the best and the worst the nation had become during the Gilded Age: a brilliant corporate raider, Morgan had little aptitude for running a company or making anything but money. A “pious Episcopalian” in an age that did not require these quotation marks, he bribed politicians and lavished money on his mistresses. An educated gentleman by New England standards, he cultivated the arts by spending top dollar on relics of a previous generation’s fashions. The Met of recent years, with its vulgar huckstering, suspicious business practices, and pretentious hypocrisy, really is the fulfillment of its patron’s character.

The Metropolitan became temporarily famous under the reign of director Thomas Hoving and his team of professional art vandals. Hoving cashed in the Met’s unparalleled collection of ancient coins and sold off major works in order to stage his publicity coups. The greatest of his stunts, the acquisition of a Greek vase looted from Italy, was Hoving’s downfall, but most of the great museums of the United States routinely waste their scarce resources on blockbuster exhibitions that have all the good taste of a Hollywood opening. The crowds come in to gawk at the famous pictures in the same way they would gawk at Bruce Willis or David Letterman if they made an appearance at the mall.

The Met, which during its over-frequent special exhibits can be as nightmarish as the Louvre, has the broadest and deepest collection of art in the New World. To me, it has always seemed an ugly place, dingy and soiled, to house so much beauty—a Greek revival bordello that has seen too much business. From its collection of ancient vases and sculpture (not so good as the British Museum’s) to its great Impressionists (inferior, in my opinion, to the Art Institute’s, to say nothing of the D’Orsay’s), the Met represents, far better than the National Gallery, the American claim to be an imperial civilization.

Museums are an exercise in cultural self-definition, and the Met’s newer collections of Native American bric-a-brac, African primitives, and contemporary junk are attempts to redefine America as something other than a purely European colony. Nothing, by the way, gives a better indication of our failure than the creeping Third Worldism that has infected the West’s educated classes since the late 18th century, when oriental art was all the rage. There was, however, some excuse for an imperial nation falling for chinoiserie. While “I do not long for all one sees that’s Japanese,” Chinese and Japanese porcelains arc undeniably beautiful artifacts of high civilizations. The best I can say of most native primitives is that they are no uglier than most contemporary art. (Much of Third World art is so bad, it might have been supported by NEA grants.)

A museum is no place in which to look at paintings. Like the European tour, the great museum is a fast-food experience, programmed, packaged, and ultimately stultifying. It is better to see two or three good paintings in a single poorly lit church than to walk through a long cafeteria line of masterpieces. Museums, in general, are places to put dead things in: dinosaur fossils and grave goods, and works of art that were once bursting with life are buried in the clean, well-lighted catacombs of the National Gallery.

An indefatigable museum-goer might agree with the general principle. “But where,” he (more likely she) will ask, “could we see these things, if there were no museums? Most of us do not count Gettys and Morgans and Guggenheims among our acquaintances.” In the first place, I shall try to explain, art for the masses is an entirely bourgeois idea. Imitating the taste and manners of the old aristocracies, the commercial classes were forced to democratize their principles to avoid being taken for parvenus. The bourgeoisie always spoke for the nation, when it was claiming a privilege. In setting up the great national museums, the goal was to acquire a veneer of culture on the cheap.

The masses may have been indoctrinated into thinking they want art for their children, but for themselves, they prefer Married With Children or Eddie Murphy goes Disney. A vital civilization is marked by a certain populism. Greek tragedy, Jacobean drama, Italian opera all had broad appeal. In more degenerate ages, a serious devotion to painting and music has always been confined to small groups, and for the real enthusiast, obstacles to gratification only intensify his passion and his pleasure.

The opposite of the tour is the pilgrimage. Nineteen ninety-two was the 500th anniversary not only of Columbus’ discovery of the New World but also of the death of Piero della Francesca. Not terribly well-known in his own life and subsequently ignored, Piero came into his own in the late 19th century. In recent years large numbers of art-lovers have made the “Piero pilgrimage” so famous that it has even reached the notice of the Smithsonian magazine (December 1992). Although some of Piero’s paintings can be found in London’s

Leave a Reply