Murray Rothbard recently described American conservatism as “chaos and old night.” Apart from the nasty implication that we are all dunces, there is something to what he says. It is getting harder every year to figure out just what it is that makes a conservative. Consider Newt Gingrich-the Carl Sagan of politics. He wants to colonize the stars, mine the galaxies for precious minerals, and open up the entire universe to free trade and economic opportunity. In between star treks, Gingrich plans to alter the government of South Africa and become President of the United States (but he won’t take office till the year 2001). The most astonishing part of the Georgia congressman’s program is the label: conservative opportunity society. Opportunity, we understand, but conservative? If ever there was a politician who exemplified the liberal temper of the American mind, it is Newt Gingrich. He is undoubtedly a force for good in the Congress and is unquestionably one of the most ingenious thinkers in Washington, but if he is a conservative, then what does that make Senator Helms?

Does the word conservative have any substantial meaning in the l980’s? The John Birch Society is typically described as conservative, but so is Milton Friedman and so was Jimmy Carter, in the beginning-the one, a libertarian free trader, the other, a welfare statist who sacrificed U.S. interests all over the globe. T. S. Eliot and Richard Weaver were also conservatives. Would either of them have been able to sniff out any conservative pheromones in Friedman’s pronouncements on freedom or in Mr. Carter’s sermons on compassion? With the success of the Reagan Revolution, however, no sane person (I do not speak of academics) is willing to admit publicly that he is a liberal. To paraphrase Edward VII on socialism, you can say we’re all conservatives now.

Ah well, tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis — times change, and we must get on the bandwagon before the music stops playing. A conservative, after all, might be nothing better than a man determined to hold on to what he’s got, what Russell Kirk called Fafnir conservatives. Peter Viereck thought it was conservative to preserve the status quo post-New Deal. This sentiment of stupid conformity and blind faith in the present is not to be dismissed lightly. A man holding onto a window ledge by his fingertips on the 50th floor is generally right not to let go. There are times when the only thing keeping the American democracy from exploding into 225 million dissociated atoms is just this unreasoning attachment to the way things are — or the way we think they are.

But if there is no more to conservatism than habit and prejudice, it may well deserve Mill’s nickname for the Tories, “the stupid party.” It is one thing to rely on the wholesome stolidity of the masses but quite another to confuse bigotry with political philosophy. Burke celebrated the solid virtues of the British nation by comparing them with contented cattle. He did not, however, elevate mooing to the level of oratory. But Burke was not a democrat. He did not live in a democratic country. We are differently placed, and it is the great temptation of our political leaders to take their principles from poll data and election returns.

In a democratic society like ours, political thinkers are all the more obliged to be very clear about first principles, precisely because almost nobody else cares. In the heat of the moment, our political leaders will say or do almost anything, so long as it puts them on the crest of a popular tide. (In their rhetorical passions they are almost as convincing as a boy in the backseat at a drive-in movie, and they show us almost as much respect the day after the election.) Even our President, ordinarily a very sensible man, cannot resist the temptation. Casting about for signs of wholesome ness in the nation, he lights upon a girl military cadet-as if our affirmative-action armed forces were not in dreadful shape.

It is time for political thinkers to persuade political leaders to consider the consequences of their policies. It is not enough to know which way to vote on the MX missile or a tax proposal. Parties and policies change, and it may only take a decade to render all our hardware obsolete. Statesmanship must be more than a matter of rigging elections or cobbling legislative bills. It requires a vision of what American society should be like and of the way it ought to work. It requires, in other words, a political philosophy, standards by which we can judge all the candidates, issues, and programs that are paraded before us, like so many bathing beauties, on the evening news.

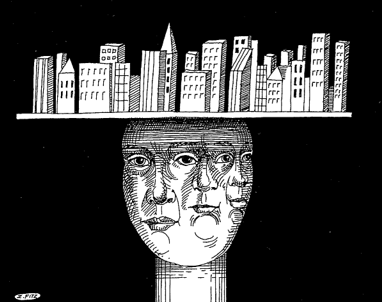

Is there anything like a conservative political philosophy at work in America today? I think not. At least, there is not one philosophy. There are, however, several philosophies or visions which can be described as, conservative without doing too much violence to conventional opinion. Three such visions immediately come to mind: democratic capitalism, reactionary Catholicism, and middle American populism. These are not the only visions, and almost nobody is purely one or the other, but these three — especially on the extreme — are different enough to serve as models.

DEMOCRATIC CAPITALISTS have reason to be proud. It is their efforts which have put the U.S. on the road to economic recovery and have inspired a mood of national ebullience which would have been unthinkable in 1980. In a way, they are the Arminians of the conservative reformation: free will is everything and the marketplace is the mechanism for solving most problems of the human flesh. They exhibit an almost boundless faith in the human capacity for transcending material limitations and speak of unleashing human energies and resources with the same optimism older conservatives used when they spoke of unleashing Chiang Kai-shek against the Communists. With considerable justification they point to the great triumphs of democracy and the free market in Europe and the U.S.: unprecedented standards of living, political stability, and — above all — the freedom of choice we enjoy, freedom to worship, to read, write and publish, to vote as we please.

Their vision of America is of hundreds of millions of individuals, each pursuing his own goals and helping to determine by his vote the sort of society we live in. By majority rule we even determine our social priorities and the kinds of institutional restraints we are willing to impose on ourselves (here they usually part company with the libertarians). Still, nothing is completely exempt from the laws of the marketplace, not even questions of morality and religion-Michael Novak speaks of the empty shrine at the heart of our civil religion. Communism and socialism are the enemy, not because they are varieties of “atheist materialism,” but because they impose coercive restraints on the free market of ideas as well as goods. To those who would restrict our freedoms in the name of social justice — Catholics as well as Marxists — their reply is simple. They ask us to judge by results. “Social justice,” in Soviet Russia or Catholic Latin America, means, in the end, nothing but poverty, class divisions, and oppression.

REACTIONARY CATHOLICS are suspicious of any ideology that leans too heavily on the idea of economic man. Pius IX and Leo XIII were almost equally hostile to capitalism and socialism, because they undermined the social order and diminished the quality of Christian chari ty. Freedom they regard as a good thing but not as an absolute. More important is our vision of human life, its purpose and nature. We cannot fall back on freedom as a first principle, because it only begs the question: free to do what, to pursue virtue or just make money? Although many conservative Catholics have made their peace with capital ism, others prefer to remain aloof.

An eminent Catholic philosopher once tried to explain to me why he did not consider himself a conservative. “You see,” he said, “you would like to preserve the rich in their power and privileges, while I want to tear them down.” If by the rich, he meant not hardworking businessmen, but the sort of degenerate rabble that attempts to pass itself off as an American aristocracy, it is hard not to sympathize. The Catholics share with “traditionalists” and Southern agrarians a concern for family, community, and the common good, which they regard as higher priorities than the right to amass wealth. The cult of individuality is the corrosive acid that eats away at the social fabric, divides families and communities, and encourages the profit-seeking dislocations that characterize so much of life in modern America. But their concern for virtue does not lead them to embrace clerical fascism or any form of the totalitarian state, because they recognize (with Aquinas) that law and the state exist only to make the virtuous life possible: virtue cannot be compelled.

POPULISTS are the black sheep of conservatism, and there are those who deny them even the slightest connec tion with “the movement.” Still, without the support of hardhats, farmers, and antiabortionists, hardly anyone pro fessing conservative sentiments could be elected to national office. Since populism is by definition a mass movement, it has produced no philosophers, but there are a few political analysts who are not completely unsympathetic: Kevin Phillips, Robert Whittaker, and Samuel Francis. Whit taker, in particular, sees populism as a series of uprisings against entrenched elites.

What most populists seem to want most is control over their own lives. They want the government off their backs and out of their businesses, homes, and schools. They would like to reestablish community consensus as a basic principle and do not understand how a bunch of deracinat ed intellectuals and bureaucrats can force them to tolerate drugs, pornography, and abortion clinics in their own hometowns, and gay bars in their neighborhoods. Some of them are socially libertarian and even vaguely countercul tural: they sing along with Charlie Daniels, when he warns, “leave this longhaired country boy alone.” Others have an ethical vision that is, however simple, closer to Aquinas than to the democratic capitalist creed of freedom at any cost, and while they would like much lower taxes and complain about welfare fraud, they do not necessarily think a nation can turn its back on the poor. Some of them have spent enough time out of work to appreciate Unemploy ment Compensation and do not quite trust all this talk of high tech and an opportunity society. Opportunity for whom?

What holds these groups together, New Right and Old Right, hardhats, and traditionalists, is our hostility to the common enemy: the left. But it is a shaky coalition. The populists have a very old alliance with the Democratic Party, one that could be revived if a benevolent plague thinned out the party leadership. Apart from the President and Jack Kemp, Republican politicians do not know how to charm the populist masses. As for whatever is left of Catholic conservatism and other traditionalist groups, their big complaint (shared by populist social conservatives) is that the President and his friends consistently put economic issues above social issues. They can be heard to mutter, on occasion, that the eventual capitalist response to abortion will be to tum it into a growth industry by providing it with tax incentives.

Perhaps the only thing keeping the conservative minds on the same range of frequencies is our very American and conservative habit of avoiding discussions of first principles. Once we begin telling each other what we really think; the alliance could go on the rocks like a marriage destroyed by too much candor. Nonetheless, we are going to have to make the effort, however painful. We are confronted with too many urgent questions and pressing problems which cannot be solved by our usual “live for today, tomorrow we die” approach to policymaking. Back in the 50’s, conserva tives were engaged in a constructive-albeit sometimes passionate-dialogue. Perhaps it is time to reopen some of the old issues and benefit from the wisdom of the Founding Fathers, not so much in the expectation of finding answers (I certainly don’t have them) but as a part of a continuous discipline which we ought to impose on ourselves in our muddled effort to clarify where we stand. If we cannot make up our minds about what we are living for, we shall soon find our minds made up for us by circumstances and by the usual lowest common denominator of politics: the ancient calculus of survival and power. “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

-Thomas Fleming

Leave a Reply