England’s Unquiet Oracle

John Enoch Powell led an extraordinary life. Twenty-five years after he died, he continues to divide.

After his death in February 1998, aged 85, his body lay in state overnight in Westminster Abbey, and tributes were led by former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. At his High Anglican funeral the following day in St. Margaret’s Church, opposite the Abbey, were former Prime Minister John Major, future Conservative Party Leader Michael Howard, the author and diarist Alan Clark, who had been a minister in Thatcher’s government, and other leading Conservatives. Nonpoliticians also crowded in, or waited outside, to see Powell’s flag-draped coffin driven off to his final resting place in Warwick. Some of the attendees told reporters what has become a cliché about Powell: that he was “the greatest Prime Minister we never had.”

But Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Labour government then in power, which should have sent a leading politician to honor a former minister who had served 37 years as a member of Parliament, dispatched only a middling-level functionary. The only other Labour parliamentarian to attend was Tony Benn. Although often at odds with Powell, Benn shared his detestation of the European Union and had an admirably nonpartisan regard for his fellow parliamentarian.

Some clerics expressed uncharitable opposition to Powell’s lying-in-state (although he was entitled as a long-serving churchwarden at St. Margaret’s) based on his famous 1968 speech, in which he warned that immigration would lead to bloodshed. The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Coggan, told the BBC, “Anything that would exacerbate the memory of that speech is to be regretted.” Some leftists slavered in schadenfreude, with the Socialist Review publishing a raving obituary that denounced Powell as “a racist to his bones.”

He was a racist pig of the most despicable variety. … Almost licking his lips, he looked forward to race riots. The effect of his speech was to unblock a racist sewer and send it swirling freely through public life. The word went round—if Enoch Powell MP said these things, they must be true!

The “Rivers of Blood” speech, for which Powell will always be remembered, whether in admiration or execration, occurred on April 20, 1968, as an address to the West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre in Birmingham. Over 45 televised minutes, Powell enthralled the room, electrified the nation, and exposed dark anxieties that underlay the public image of the “swinging Britain” of the 1960s.

Powell was then Shadow Secretary of State for Defence for the Tories under the leadership of Ted Heath. The measures his speech called for were Conservative Party policy: reducing immigration and encouraging voluntary repatriation. He also cited approvingly a Labour politician who had decried Sikh demands for special treatment. Labour had just passed stringent restrictions on immigration through the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, reducing the number of Kenyans eligible to enter Britain. Labour Home Secretary James Callaghan was reported to have told Benn that “we don’t want any more blacks in Britain.”

Powell was speaking three days before a parliamentary debate on Labour’s Race Relations Bill proposing a civil rights nondiscrimination law and articulating common concerns about that bill’s provisions on housing and employment, which Conservatives saw as further infringing on rights of association and expression already curtailed by 1965 legislation. Powell’s aim was to avoid division, and he opposed any notions of racial superiority. It was nevertheless inevitable that his speech would attract negative attention beyond Birmingham. As the BBC that day predicted, “It is likely his comments will be less warmly received by the Conservative party leader, Edward Heath.” Powell himself anticipated a “chorus of execration.” He may not have realized quite how cacophonous that chorus would be—although even if he had, he would not have desisted.

The day following the speech, Powell was sacked from the Shadow Cabinet, and his face was plastered on the front pages of the papers. He was made out to be a bogeyman to an influential minority, but he became a hero overnight to millions more, especially in working-class districts adversely affected by large-scale, rapid immigration to Britain from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

As ideological and political denunciations against Powell mounted in quantity and intensity, London bus drivers left their buses in the road to march in his support, joining meat porters from Smithfield Market and Thameside dockers in a mass demonstration that was in part an outburst of relief that a politician was finally articulating their fears. More than 110,000 letters of support flooded into his office. A Gallup poll found that 74.4 percent of Britons agreed with him.

If the content of Powell’s speech was mainstream by 1968 standards, his mode of expression was strikingly demotic. Using street-level language, he quoted angry constituents: “In this country in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.” He talked about a war widow—the only white remaining in a once-respectable street, with her windows being broken and excreta pushed through her letterbox—afraid to go out because

when she goes to the shops, she is followed by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies. They cannot speak English, but one word they know. “Racialist,” they chant. When the new Race Relations Bill is passed, this woman is convinced she will go to prison. And is she so wrong? I begin to wonder.

Such people as this widow had, he said, “become strangers in their own country … unable to obtain hospital beds in childbirth, their children unable to obtain school places, their homes and neighborhoods changed beyond recognition, their plans and prospects for the future defeated.”

Powell’s concerns for constituents cut adrift were given yet greater force by his prediction that mass immigration could lead to civil war, a growing risk that he compared to a “cloud no bigger than a man’s hand, that can so rapidly overcast the sky.” Mass immigration was, he said, like “watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.”

At this point in the speech the plain parlance he used donned classical robes, as he enlisted the Aeneid to unforgettable effect: “As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’”

The import and tone of the “Rivers of Blood” speech were uncompromising—and unwelcome to many cautious Conservatives, with even Margaret Thatcher regarding it as “strong meat.” Powell’s phraseology is held against him still by more pliable Conservatives, arguably as an excuse for their own inaction. He was accused of fomenting violence, when his aim was the opposite.

Powell’s speech blamed Britain’s growing immigration problems on those who refused to acknowledge them— “writers of the same kidney and sometimes on the same newspapers which year after year in the 1930s tried to blind this country to the rising peril which confronted it, or archbishops who live in palaces, faring delicately with the bedclothes pulled right up over their heads.” As he remarked in his peroration, “To see, and not to speak, would be the great betrayal.”

Ancient ideas were inseparable from Powell’s philosophy. Born in Birmingham in 1912, he was the only child of two teachers, and his mother taught him Greek when he was still very young. At the age of three, he was nicknamed “the Professor” for his habit of lecturing to his parents. Excelling at school, where he was nicknamed “Scowly Powelly,” at 17 he went on to Cambridge, where his tutors included the poet A. E. Housman, whose collection A Shropshire Lad Powell said he could never hear without weeping, even in old age. He graduated with a double first in Latin and Greek. “I was a learning machine,” he told BBC Radio in February 1989. He said he arose at 5 a.m. to devote an hour-and-a-half to Herodotus before breakfast. He longed to be a classical scholar, opting to use his middle name over his first name because there was already an eminent classicist named John Powell.

At 25, he was a professor of Greek at the University of Sydney, in Australia, the youngest professor in the Empire but increasingly agitated by the war he farsightedly foresaw in Europe. His existence while he waited for its outbreak was “only provisional,” he told the BBC, and it was with “joy and relief” that he returned to Britain in 1939 and immediately enlisted as a private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. On the four-week journey home, he had learned Russian, one of 12 languages he would eventually command, including Welsh (his great-grandfather had been a Welsh coalminer) and Hebrew.

Powell fully expected to be killed, but this held no horrors for a man who truly believed Horace’s dictum, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”). War, although terrible, was to him the ultimate clarifier, making action and allegiance as one. He believed a man should be willing to sacrifice himself for a nation with which he felt a mystical and organic connection, motivations ironically resembling those of his German opponents, who had likewise wallowed in the patriotic Weltanschauung of Wagner. But the would-be Siegfried was picked out for promotion and service in military intelligence, eventually becoming the youngest brigadier in the British Army, and helped to plan the Battle of El Alamein. For the rest of his life, he would bear survivor’s guilt, telling interviewers that he wished he had died in the war—a feeling exacerbated by witnessing his beloved country’s inexorable postwar decline.

He was posted to India in 1943 and became besotted with the country; he told his parents that year, “I soaked up India like a sponge soaks up water.” He yearned to become viceroy and to that end learned to speak Urdu. He was bitterly disappointed by the 1947 decision to grant India independence. From that moment, he regarded the Empire as irretrievably lost and nostalgia for the Raj as a decadent diversion.

Back home, he launched into politics and was elected in 1950 as member of Parliament for Wolverhampton South West. Parliament, with all its resonances and ritual, embodied England for him, and he soon developed an oratorical reputation, particularly because of a powerful July 1959 speech denouncing the brutal treatment of Mau Mau rebels in Kenya. He was an unlikely politician even by starchy 1950s standards, with his Old Testament name, his three-piece suits, his unsmiling stiffness before cameras, his basilisk-staring with slightly protuberant eyes, and his pedantic, remorseless delivery of logic in a nasal West Midland monotone.

There is an apocryphal anecdote of Powell and friends holding a competition to ascertain who could best mimic his voice—and he came in third. His freezing public persona was belied by sardonic wit, exemplified later when asked why Prime Minister Heath hated him so much. “Mr. Heath is a methodical man,” he reflected on his portly ex-leader. “I think he must once have missed an important lunch engagement, and it preys on his mind.”

In 1955, Powell became a junior housing minister under Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and, in 1957, financial secretary. Already notoriously unbendable, he resigned, after just a year, out of a principled belief that Macmillan’s government was spending too freely. He was a Thatcherite before Thatcher; in 1965, Austrian School economist Friedrich Hayek would say, “All our hopes in England now rest on Enoch Powell.”

But economics always came after national interests for Powell. In 1960, he became health minister, responsible for one of the largest-spending departments. He strongly believed in free healthcare for all Britons and sought to shut down inhuman lunatic asylums. He recruited medical staff from Commonwealth countries, which opened him up to accusations of hypocrisy on the subject of immigration in 1968, after his “Rivers of Blood” speech. He always saw these staff, however, as temporary residents to be welcomed while in Britain but who would then return to their own countries with the benefit of new skills.

Powell’s lyrical love of England is reflected by another speech, to the Royal Society of St. George on St. George’s Day in 1961, in which he bent Attic lore to English ends:

Herodotus relates how the Athenians, returning to their city after it had been sacked and burnt by Xerxes and the Persian army, were astonished to find alive and flourishing in the midst of the blackened ruins, the sacred olive tree, the native symbol of their country. So we today at the heart of the vanished Empire, amid the fragments of demolished glory, seem to find like one of her own oak trees, sturdy and growing, the sap still rising from her ancient roots to meet the spring, England herself.

And when addressing a Manchester dinner in 1965, Powell quoted the Third Witch in Macbeth: “If we are not to be powerful and glorious ourselves it is some compensation to think we belong to something powerful and glorious … ‘thou shalt get kings, though thou be none.’”

After his expulsion from the Shadow Cabinet in 1968, he migrated majestically to the back benches, a rumbling volcano watched warily by party managers. He and Heath would never speak again, but Heath could not dispense with his services, because Powell appealed to millions who were usually off-limits to Conservatives—not just working-class voters but also celebrities like rock stars Rod Stewart and Eric Clapton.

“I think Enoch is the man,” Stewart said in 1970. “I’m all for him. This country is overcrowded. The immigrants should be sent home.” Powell was widely credited with winning that year’s election for Heath. He was more than once asked to consider founding a new party, but always demurred, which, in retrospect, may have been a mistake.

In 1976, Eric Clapton said to Birmingham concertgoers, “Do we have any foreigners here tonight? If so, please put up your hands. Any wogs, I mean,” Clapton said, using a British slur for nonwhites. “Well, wherever you all are, I think you should all just leave,” he continued. “Not just leave the hall, leave our country. I think we should vote for Enoch Powell.”

Powell’s dislike of immigration was matched by his detestation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor to the European Union. As Heath sought UK entry, Powell found himself on the same side as the Labour Party, which wanted to renegotiate the Treaty of Brussels and offer a referendum on EEC membership. In a speech in Birmingham, Powell said the key issue was whether Britain was to “remain a democratic nation … or whether it will become one province in a new Europe superstate.” He argued it was a “national duty” to oppose those who had deprived Parliament of “its sole right to make the laws and impose the taxes of the country.” Independence trumped all abstractions; as he would tell a possibly nonplussed March 1982 meeting in Ilford, “I would sooner receive injustice in the Queen’s courts than justice in a foreign court.”

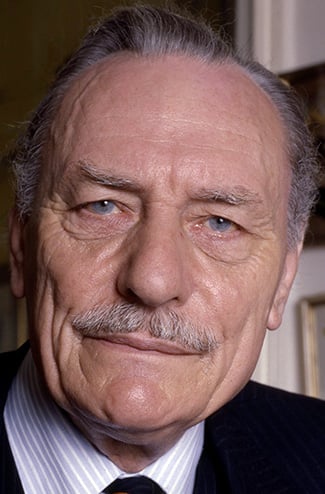

in London (Allan Warren)

Five days before the February 1974 election, Powell recommended voting for Labour—and when he heard the following morning that Labour had won, he sang the “Te Deum” hymn of joy and thanksgiving in his bath. Many Conservatives never forgave this, but by now, Powell had left them behind, and in the October 1974 election he became Ulster Unionist MP for South Down, which seat he would represent until leaving Parliament in 1987, greatly boosting the Unionist cause with his public profile and forensic constitutionalism.

But this sideways step also removed any lingering possibility of leading wider campaigns. Powell was, however, still hugely respected; the Commons chamber or public meetings were crammed whenever he was scheduled to speak. He defended fox hunting, Ulster, and the Falklands War. He called the UK’s independent nuclear deterrent an “unaffordable farce,” decried British deference to the United States, and claimed Lord Mountbatten had been killed by the CIA. Reprising his sometimes liberal stances on particular issues, he also opposed hastily introduced draconian antiterrorism legislation and supported abolishing the death penalty and decriminalizing homosexuality.

His chivalric attachment to monarchy did not prevent him from criticizing the Queen’s 1983 Christmas broadcast for focusing on the Commonwealth, which he believed suggested “that she is more concerned for the susceptibilities and prejudices of a vociferous minority of newcomers than for the great mass of her subjects.”

He also denounced the first Gulf War on a noninterventionist stance. “The world is full of evil men engaged in doing evil things,” he said. “That does not make us policemen to round them up, nor judges to find them guilty and to sentence them. … I sometimes wonder if, when we shed our power, we omitted to shed our arrogance.”

Senior Conservatives and later UK Independence Party figures often invoked Powell in support of monetarism and Euroskepticism, and in 1979, Margaret Thatcher channeled him on immigration, saying that she understood why many voters should feel they were being “swamped.” Even after he had left politics to devote himself to biblical exegesis, he remained inseparable from any discussions of national identity and was a continual presence in such venues as academic debates about Europe, arguments about ethnic quotas, or the controversy of Boris Johnson dropping the word “piccaninnies” casually into an article.

“The age of Brexit is the age of Powell,” Paul Corthorn, his latest biographer, has concluded—not to mention the age of Black Lives Matter. Old enemies are compelled to agree. “The ghost of Enoch Powell hangs over Britain … with a smile on its thin lips” repined The Guardian’s Nick Cohen. “For a politician inexplicably famed for the banal observation that ‘all political careers end in failure’, Powell is enjoying a posthumous victory.”

Leave a Reply