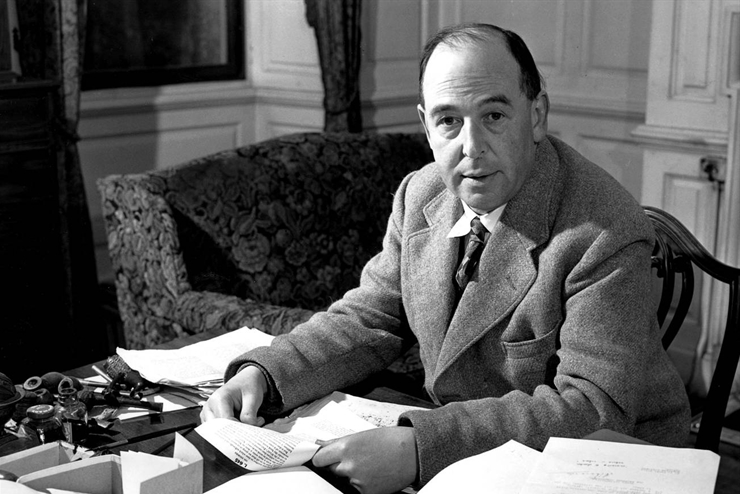

C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) is arguably the most influential Christian writer of the 20th century. To tell the story of his life is to speak of a remarkable journey out of youthful skepticism into the joyful discovery of faith; of an embattled defense of traditional moral sanity; and of a profound artistry in the creation of fictional worlds that has touched the lives of millions around the globe.

Among his works of Christian apologetics, The Screwtape Letters (1942) and Mere Christianity (1952) continue to be best sellers more than half a century after his death. His literary criticism, such as The Allegory of Love (1936) and A Preface to Paradise Lost (1942), are still required reading for many graduate students in English. And The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956), a series of children’s stories, have sold more than 100 million copies.

Despite this spectacular success in connecting with readers, Lewis liked to call himself a dinosaur. In his 1954 inaugural lecture as the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Magdalene College, Cambridge, Lewis explained that he was one of the last living specimens of “Old Western Man,” someone whose worldview was grounded in classical learning and shaped by Christian faith. He applauded his newly created title, saying that the continuity between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was much greater than any changes that might have occurred during the years encompassing those two eras.

Lewis was also fond of saying that “The Renaissance never happened in England. Or if it did, it was of no importance.” He added that there was a much more significant divide in England between the largely Christian era of Walter Scott and Jane Austen and the increasingly post-Christian world of Victorians such as Matthew Arnold or even Charles Dickens. Lewis noted that the famous Dickens novella A Christmas Carol lauds generosity and goodwill, but never actually touches upon the historic foundation of Christmas celebrations.

Lewis was the son of a successful Belfast attorney, and his early childhood seemed to him in retrospect to be a kind of lost paradise. Then, when he was nine, his mother died of cancer, and he was sent off to boarding school in England less than a month later. At his first school, Wynyard, outside of London, he was traumatized by a cruel schoolmaster, who was later charged with abusing his students and declared legally insane. Things were no better when he moved on to Malvern College, a private preparatory school where, although the teachers were kinder, the young Lewis felt that he was surrounded by “coarse, brainless English schoolboys.”

Lewis’s childhood Christian faith did not long outlast his departure from Ireland. Raised in the polarized world of Catholics versus Protestants, Lewis discarded in his early teen years what his brother Warren called “the dry husks of religion.” Even in his skeptical years, however, Lewis was not attracted to political liberalism as a kind of substitute religion. In his memoir Surprised by Joy (1955), Lewis explained, “I am astonished that I did not progress into the opposite orthodoxy—did not become a Leftist, Atheist, satiric Intellectual of the type we all know so well.” He surmised that his innate romanticism and deep-seated pessimism seemed to dismiss any notions about humans being able to construct an ideal social order for themselves. Immanuel Kant once said, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity nothing very straight can be built,” and Lewis would surely have agreed.

During his twenties, Lewis became increasingly skeptical of his own skepticism. Initially, he had accepted what he called “the argument from Undesign,” which was founded on the assumption that human history, perhaps cosmic history, had no discernible plan or purpose. The young Lewis relished the memorable lines from the Roman poet Lucretius: “Had God designed the world, it would not be/A world so frail and faulty as we see.” Eventually, though, Lewis began to ask himself, if this world was created by a “Brute and a Blackguard,” how did we come to discover that fact? By what standards might we judge such a creator to be a moral monster? In matters of taste, one might favor Bach over Beethoven, or vice versa. But in choosing, say, the Allies over the Axis powers in World War II, there must surely be an objective—not merely conventional—moral norm by which to judge one side superior to the other.

As Lewis was beginning to suspect that there are indeed objective moral standards, he also came to conclude that there were objective standards for judging truth as well. When Freudians and Marxists argued that all assertions of truth are distorted by psychological complexes or class prejudices, Lewis asked how they themselves escaped these distorting effects. In The Abolition of Man (1943), Lewis argued that the universe is governed by an overarching set of moral norms, which he called the Tao, built into the very fabric of the universe.

As Lewis was beginning to suspect that there are indeed objective moral standards, he also came to conclude that there were objective standards for judging truth as well. When Freudians and Marxists argued that all assertions of truth are distorted by psychological complexes or class prejudices, Lewis asked how they themselves escaped these distorting effects. In The Abolition of Man (1943), Lewis argued that the universe is governed by an overarching set of moral norms, which he called the Tao, built into the very fabric of the universe.

For Lewis, the great tragedy of the 20th century was the loss of confidence in objective moral norms and an objective sense of truth. In his essay “The Poison of Subjectivism” (1943), Lewis stated bluntly, “Unless we return to a crude and nursery-like belief in objective values, we perish.” In the novel That Hideous Strength (1945) Lewis’s protagonist, Elwin Ransom, ponders a sinister new direction in the natural sciences: “The physical sciences, good and innocent in themselves, had already, even in Ransom’s own time, begun to be warped, had been subtly maneuvered in a certain direction. Despair of objective truth had increasingly been insinuated into the scientists; indifference to it, and a concentration upon mere power had been the result.” Since Lewis’s time, this indifference may be said to have progressed much further in the humanities and social sciences than in the physical sciences.

Of course, such an attitude put Lewis at odds with most of his contemporaries. Like his close friend J. R. R. Tolkien, Lewis always adhered to traditional canons of literary taste, renouncing modernism and all its works. When the painter and novelist Wyndham Lewis and his friends published their short-lived journal of the Vorticist modernist movement, Blast, C. S. Lewis contemplated a competing journal called Counterblast, which would feature traditional styles of poetry and fiction. That project never got off the ground, partly because Blast itself folded after only two issues.

Lewis attempted to engage with the products of literary modernism, but his reactions were consistently negative. At Oxford, T. S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” was sometimes called “The Waste Basket.” Lewis remarked that “Dante is not infernal poetry, but ‘The Wasteland’ is.” He wondered if later critics would label 20th century poetry as “the whining and mumbling period.” Lewis felt no better about modernist fiction, saying that he would rather walk a treadmill than read James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). In The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), he satirized D. H. Lawrence as the sex-obsessed Mr. Phally.

From another lifelong friend, Owen Barfield, Lewis borrowed the term “chronological snobbery” to describe the widespread notion that contemporary thinkers are somehow more evolved than previous generations, that everyone from classical writers to the Victorians were confused and benighted in comparison to the present day. What others would call “stagnation,” Lewis called “permanence.” While others might label new ideas as dynamic, bold, or courageous, Lewis always wanted to know simply whether they were true.

While Lewis could quote from memory philosophical and literary texts from Plato to Peter Pan, he took very little interest in politics. He called contemporary democracy “govertisement,” government by means of slogans and advertisements. He was particularly contemptuous of progressive politics, arguing that the abandonment of traditional moral norms led not to advancement, but to cultural chaos and a loss of meaning.

In one letter, Lewis joked about joining an organization called “The Society for the Prevention of Progress.” In That Hideous Strength, he portrays the self-proclaimed “Progressive Element” as trying to construct a fascist state in England while unleashing actual demonic forces. In one of the “Narnia Chronicles,” The Silver Chair (1953), the progressive school called Experiment House is dominated by sadistic student bullies who are not chastised by their teachers but rather treated as fascinating psychological specimens.

In 2013, the 50th anniversary of his death, Lewis’s memorial stone was placed in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey. It seems an ironic tribute to someone who spent most of his twenties trying and failing to find renown as a poet. He eventually decided instead to write about the things that stirred his own depths—imagination, story, and faith. In accepting that humbler view of himself at about age 30, Lewis soon launched upon one of the most remarkable writing careers of the 20th century. His memorial stone is inscribed with one of Lewis’s most oft-quoted sayings: “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”

Image Credit:

above: C. S. Lewis

Leave a Reply