Defender of Great Books

In her book Open Secrets/Inward Prospects, Eva Brann declared her love for two communities that have both had a founding and re-founding: America and St. John’s College. Brann’s teaching and writing afforded her an opportunity to study America, and America afforded her an opportunity to study the events that made a country.

A naturalized American citizen, Brann’s affection for her new home did not cloud her critical assessment of its history. She examined the nature of a country that declared independence, advanced the ideas of equality and liberty, instituted a government based upon consent, and secured rights, and then, generations later, responded to the secession of several states that called the founding principles to the forefront of debate. Her quest to understand affirmed that there was something unique about America worth preserving and perpetuating.

Fleeing Nazi Germany, Brann came to America with her family at age 12. She lived in New York, studied history at Brooklyn College, and earned a Ph.D. in classics and classical archaeology from Yale. St. John’s College, where she spent her entire teaching career of more than 60 years, still offers a Great Books curriculum that was refounded by the college’s long-time tutor and dean Jacob Klein, who implemented much of what is still present today. It was originally introduced in 1937 by Scott Buchanan and Stringfellow Barr. They wanted a curriculum that understood things in terms of their nature, in contrast to the historicist school that understood things in terms of prevailing practices, social setting, and history.

Brann argued in her essay, “What are the Beliefs and Teachings of St. John’s College,” that “human nature is everywhere one and that human beings … have undergone a common shaping” and “this shaping has been through a certain high wisdom and perfected art, which their authors and masters, considering that what they had thought or made was true and beautiful not only for a time but for ever, fixed for the future, most accessibly in books.”The college remains dedicated to closely reading original texts and pursuing free and radical inquiry. Brann, noted for her contributions to St. John’s and liberal arts education in general, also received public recognition for her efforts when she received the National Humanities

Medal in 2005.

Brann’s publications include several books on wide-ranging topics. An inverted pyramid serves as a visual representation to capture the rich offerings. The point depicts brief thoughts and essays, and her lengthier and more comprehensive undertakings ascend to the inverted base. First, Brann’s shortest writings include collections of aphorisms and brief reflections (Open Secrets / Inward Prospects, Doublethink / Doubletalk, Iron Filings or Scribblings) and essays published in The Past-Present, Homage to Americans, Pursuits of Happiness, and Then and Now. Second are her books on poets and philosophers (Homer, Heraclitus, Plato, and Kant) who think deeply about the world and the human activities that shape it: Homeric Moments, The Logos of Heraclitus, The Music of the Republic, and How to Constitute a World. Third are her books that focus on themes such as education, Paradoxes of Education in a Republic, feelings, Feeling our Feelings, the will, Un-Willing, equality, Is Equality an Absolute Good? and imagination, time, and naysaying in her trilogy, The World of the Imagination, What, Then, Is Time?, and The Ways of Naysaying. She also translated Jacob Klein’s Greek Mathematical Thought and the Origin of Algebra and Platonic dialogues.

Brann’s approach to education and writing was not to develop new theories, but to probe and recapture original understandings and conceptions of great thinkers. Her study of the Declaration of Independence and other founding documents illustrates this. Regarding the American tradition’s two sources, she wrote in her essay “Concerning the Declaration of Independence,”

Our tradition becomes more universal by being regarded as having two sources, one of which, the Declaration, is on a much higher level of abstraction than the second. On the other hand, the tradition is made more coherent when it is shown that that second source, the Constitution, is not only compatible but even supremely consonant with the first. The most interesting work in American political theory seems to me to deal with these matters.

She referred to the Declaration as a logos, “a work of justification and explanation, an account-giving.” She also offered an unusual assessment: “To put it in a stark way: our Declaration of Independence is a shallow text, deeply shallow. In that lies its virtue.” One can imagine a shallow body of water where the words are seen and reflected, thus inviting rumination on their meaning.

She also offered an example from poetry as part of her explanation of the depth of the document: “Much in the manner of a work of poetry—which indeed [the Declaration] literally is, since the great paragraph of ‘abstract truths’ can be read in near-perfect lines of iambic pentameter—it offers the greatest definition of view with the least restriction of thought.”

Beyond the effort to study and grasp the meaning of these fundamental works, she saw the need to teach them. She recommended that younger students learn a certain amount by heart and the older students engage in discussion of the original writings. These exercises of study and practical experience, she explained, instill respect, appreciation, and reverence. For older students, she recommended that “the Declaration should not so much be taught as talked of at every American college.” Further, in her essay “Civic Education,” she related the profound nature of these writings: “every student and every teacher should join in the discussion as if their lives depended on it—as they do.” To those who dismiss the past, she concluded her “Declaration of Independence” essay with this response:

To what then are we to look? The present, that moving band of vanishing ‘nows,’ always produces the wisdom which fits it, evanescent wisdom. The future, which we have yet to make and have some reason to fear, is in its essence non-being, and when appealed to for advice can only reflect our present ignorance. But our past, which is really our perpetual present, is what we have. So why not re-possess what is ours, the more so since it seems to be good?

Beyond the founding documents, the classics of the Western tradition, Brann argued, lead to America’s founding documents. “American democracy is its most powerful political consequence—one might even say its culmination,” she wrote. In a publication entitled “Literacy, Culture, and the Shaping of Democracy,” she explained that the culture present in America is one that is based on a literary tradition, which she characterized as “an enormous written tradition,” ambivalently labeled as “classics.”

There is thus a necessity to cultivate cultural literacy, which is expressed in terms of “necessary to our living.” She argued that it is a living that is characterized in a modern world as “the estrangement, conscious or unconscious, induced by the man-made, well-managed wilderness into which we are born.”

To achieve the ends of shaping and preserving democracy, Brann called for the “study of the central writings which are the origin and implicitly still pervade our way of life,” from elementary school through college. Good schooling as she described it, includes literacy in the Western tradition and a reaffirmation of cultural literacy. This formation of students throughout their schooling, she believed, relies upon literacy to lay a foundation for democratic institutions.

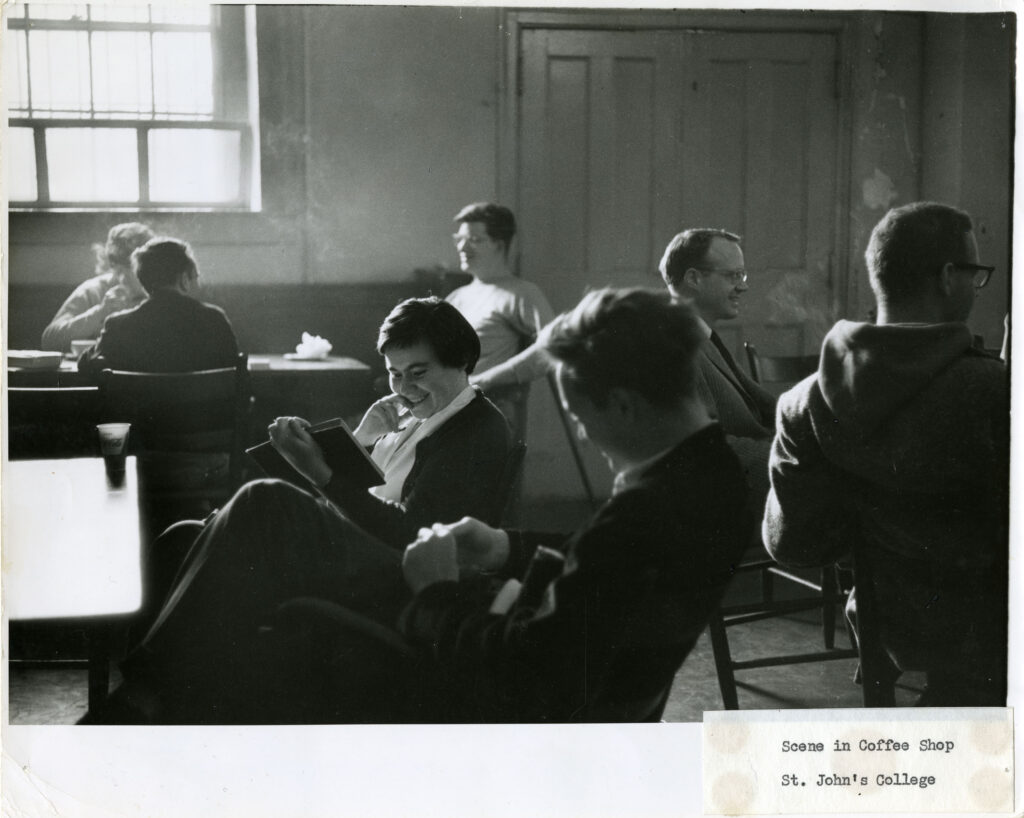

Scene in Coffee Shop, St. John’s College, circa 1960s (Unknown / St. John’s College Digital Archives)

Such a formation also has the advantage of reaching a broad base of the citizenry who are part of the American democratic republic, which prizes self-governance. Both liberal and civic education provide the foundation of building and sustaining life in a republic with democratic foundations. The extension of education beyond the classroom walls redounds to the benefit of the citizenry and the well-being of the country. “Liberal education is, from its ancient beginnings, that wide base which underlies the specific civic education of republics.” Such an education can inspire and instill virtues in the citizenry who contribute to the American democratic republic and foster and perpetuate the institutions that date from the founding.

A contrast to Brann’s close reading of texts was her cultivation of the imagination as an expansion of one’s world. She linked political concerns to the imagination in her response to the question, “Why is the imagination a specifically conservative concern so that it is rightly attached adjectivally to the noun ‘conservative?’” (She titled her essay “The Imaginative Conservative.”)

The imagination should be anybody’s interest, a common interest, for just as articulateness damps rage, so imaginativeness relieves alienation. Thus, as the preservation of expressive (non-twittering) language should be a social concern, the saving of the imagination should be everyone’s care.

Rage and alienation are both concerns, some would even say threats, in American politics, as are pitched political battles of one side against another. Yet this call to imagination and, specifically, imaginative conservatism addresses these concerns. She argued that it encourages “a grounded flexibility functioning between ideal and real, the imaginative space in which concrete specificity and universal essentiality meet—the twice-lived, once in experienced fact and again in imaginative reflection.” Moving beyond the concrete specificity is a means to break down the polarization present in politics, and moving toward the universal essentiality expands the dialogue.

I am not a great believer in philosophizing, by which I mean trying to get to the bottom of things concerning current affairs. That’s because I think there has to be some calming distance and some extended thinking for unsettling events to reveal their stable shape

Works of reflection demand what Brann called “reverse imagination,” a means to capture “incarnate truths,” as she explained in Then and Now. This idea applies to politics and conservatism.Politics oftentimes requires that we deal with the here and now, with practical, factual matters. The imagination, she explained, gives political ideas their concreteness in the sense of perceiving the consequences of these ideas but also takes us back to the truths that give rise to the ideas. Conservatives are concerned with preserving or keeping things safe, but Brann warned that they can attach themselves to things that are unworthy of preservation, or that they can be “dug in” and become oblivious. The imagination keeps the conservative from these perils, and the imaginative conservative can continue within the bounds of good political practices. As beings with imaginations, she encouraged us to think.

Brann may not have used titles such as right, left, and center, but the approach to political and philosophical studies in her writings is one that those across the political spectrum should embrace. At the beginning of her talk “On Compromise,” she made a statement on politics: “I am not a great believer in philosophizing, by which I mean trying to get to the bottom of things concerning current affairs. That’s because I think there has to be some calming distance and some extended thinking for unsettling events to reveal their stable shape.” That stable shape can serve as an anchor to grasp when discussing political topics. The anchors are found in writings of great figures from the past. They are worthy of conserving, if for no other reason than to ask questions and seek to learn from them. Brann’s teaching and writing show us the way.

Leave a Reply