The 20th Century’s Greatest Journalist

One of the few worthwhile collections of H. L. Mencken’s newspaper writing, as it appeared originally in The Baltimore Sun, The Chicago Tribune, and elsewhere, emerged in 1991 under the title The Impossible H.L. Mencken. In an otherwise laudatory review, Washington Post book critic Jonathan Yardley called the book’s title “silly.” “To call H.L. Mencken ‘impossible’ is excessively cute and unwittingly condescending,” he sniffed.

The title, selected by editor Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, was intended to suggest Mencken was too stubborn, too difficult, too exasperating—which certainly many of his readers and critics believed. Yet this was also a man who in his lifetime was celebrated as America’s Samuel Johnson and George Bernard Shaw, and compared to no less than Mark Twain for his humor and biting wit.

All of that might have been true when Mencken was active on the scene, and even 33 years ago when Rodgers was prominent in helping keep the man’s memory and legacy alive. But today the appellation takes on a different meaning. The “Sage of Baltimore’s” career and ideas simply would be impossible today.

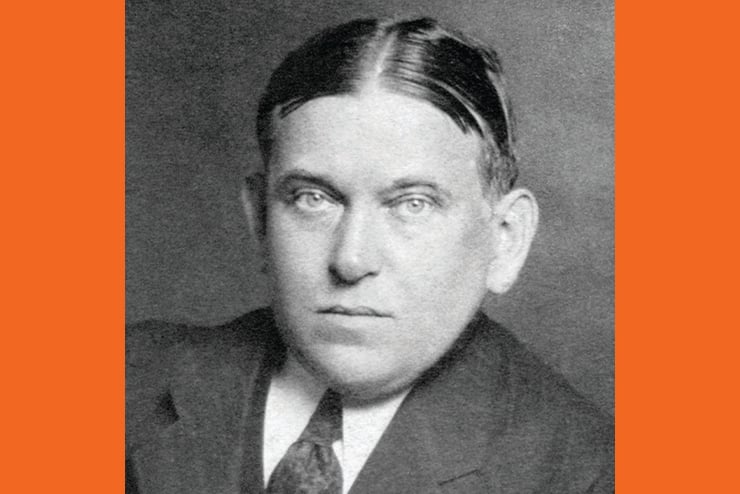

Henry Louis Mencken (1880-1956) was a great many things throughout the course of his nearly 50-year career: author, editor, critic, lexicographer, and amateur philologist. He published 39 books in his lifetime and another half-dozen posthumously. He edited two national magazines, The Smart Set and The American Mercury, the latter of which he cofounded with George Jean Nathan. But by his own reckoning, Mencken was, above all else, a newspaperman—arguably the greatest of the last century. He spent the bulk of his professional life from 1906 to 1948 writing for The Baltimore Sun, interrupted only by the two World Wars, when he believed (correctly) he could not speak candidly. (“I know by experience,” he wrote to a friend in 1945, “that in war time my very vocabulary is prohibited.”)

In his prime in the 1920s, he was, in Walter Lippmann’s words, “the most powerful personal influence on this whole generation of educated people.” The leftist literary critic Edmund Wilson, writing in The New Republic, called Mencken “the civilized consciousness of America … realizing the grossness of its manners and mind, crying out in horror and chagrin.”

Yet he had no credentials to speak of. Mencken graduated at the top of his class from Baltimore Polytechnic High School, but had no formal college education. He learned journalism through a correspondence course. One of his instructors praised his work as “written with a good deal of life and humor” but admonishing him to avoid “long and pompous words in funny passages”—advice he ignored. He broke into the newspaper business by sheer determination.

He had been fascinated with printing since he was a young boy, which could not have counted for much. Young Harry spent the summers of 1888 and ’89 with his family in Ellicott City, about 15 miles west of Baltimore by train, where he found his way into the offices of the local newspaper. “It … determined the whole course of my life,” he told an Ellicott City Times reporter in 1941. “For it was by gaping into the window of the old … Times office that I got my first itch for journalism, and to that sad, but gaudy trade all my days have been devoted.” The next Christmas, Mencken received a child’s printing press and he spent much of the day printing business cards. But the “r’s” were broken, so instead of “Henry” or “Harry,” he adopted the byline “H. L. Mencken.”

At the turn of our 21st century, a precocious young writer with a high school diploma would have little hope of breaking into newspaper work. But a century prior, it was possible for a literate young man with sense, ambition, and a willingness to work up a sweat to land work as a city reporter.

Mencken’s father, August, would hear nothing of his eldest son’s journalistic aspirations. He expected his son to take over the family’s successful cigar business. The only trouble was, Henry was a wretched salesman and had no talent for the industry. Some salesmen could sell over $1,000 worth of cigars in a month. Mencken made only $171 in sales in his first six months on the job. He floundered for nearly two years. His only solace was the copious reading after work, including the 1894 guidebook, Steps into Journalism: Helps and Hints for Young Writers.

On New Year’s Eve in 1898, a disaster presented young Henry with the opportunity he so desperately wanted: His father collapsed from a kidney infection, which would prove fatal. Young Mencken was sent out into a winter storm to find a doctor. As he ran through the snow, he would later recall in his memoir, Newspaper Days, he repeated over and over, “If my father dies, I’ll be free at last.” Less than a month later, he applied for a position at the Baltimore Morning Herald. Near the end of June 1899, he was hired. Two years later, he was editor of the paper’s Sunday edition. By 1903, he was editor of the morning edition. A year after that, he became editor of the evening edition and covered the Great Baltimore Fire.

Then the Herald went belly up in 1906. After a four-week stint at the Baltimore Evening News, Mencken landed at the paper that would shape and define the rest of his career: The Baltimore Evening Sun. It’s impossible to imagine such a rapid ascent in the bloodless, overly professionalized, and utterly hollowed-out newspaper world of today. Nor is it easy to see how Mencken would fit into the ideologically conformist, politically homogenous newsrooms of the 21st century. His politics were eccentric even for his time, and he often clashed with his colleagues at the Sun, especially over Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies and the lead-up to World War II.

Nominally a Democrat—he voted Republican only twice in his life (Warren Harding in 1920 and Alf Landon in 1936)—Mencken did not believe in democracy, which he famously defined as “the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard” and “a pathetic belief in the collective wisdom of individual ignorance.” He described himself variously as “an extreme libertarian,” “a civilized tory,” a “reactionary,” and an “extreme radical.” He dismissed the progressives of his own day as dreamers and considered “all the larger human problems … insoluble,” and so thought it a waste of his time and effort to propose any sort of alternative to the democracy he loathed.

In the end, he declared: “I belong to no party. I am my own party.”

“The two main ideas that run through my

writing,” Mencken wrote in a private autobiographical note, “whether it be literary criticism or political polemic, are these: I am strongly in favor of liberty and I hate fraud.”

Chairman Mencken of the Party of One held opinions that aligned imperfectly with the Old Right. He railed against Puritanism and Prohibition—a victory for religious Progressives—which he regarded as an affront to civil liberty. He famously defined Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” Of the 20th century American Puritan, Mencken said, he “cannot be magnanimous; he is unable to grasp the notion that it is better to yield than to injure a fellow being.” Woodrow Wilson “acted as a true Puritan” when he refused to pardon the socialist Eugene V. Debs, who had been sentenced to 10 years in federal prison under the Sedition Act of 1918 for his anti-war activities. (Debs would later be pardoned by Warren G. Harding.)

Mencken was a noninterventionist in principal but sided with Germany in World War I and World War II at first, largely on ethnic grounds. He was proud of his German heritage and loathed the British. He misapprehended Adolf Hitler as just another “gaudy demagogue” and did not foresee the scope of the Fürher’s genocidal or imperialistic designs.

He favored traditional marriage but also advocated the decriminalization of birth control and happily published Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger in the pages of The American Mercury.

He was a thoroughgoing agnostic and enthusiastic believer in the evolutionary theory of Charles Darwin. He earned lasting fame for his coverage of the “Scopes Monkey Trial” (Mencken’s moniker) in 1925, when a Tennessee high school teacher named John Scopes was prosecuted for teaching the theory of human evolution. Evangelical Christian lawyer and former Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan led the prosecution—and was the prime target of Mencken’s barbs.

Truth is, Mencken was no objective reporter of the case. He had worked with the American Civil Liberties Union to find a test case to challenge Tennessee’s law, and helped arrange for the famous civil liberties lawyer Clarence Darrow to represent Scopes. Though Scopes was found guilty and ordered to pay a fine, the verdict was eventually overturned on appeal. The goal was never to get Scopes acquitted, but to “make a monkey out of Bryan.” In that sense, it was a massive victory.

In his obituary of Bryan, who died just days after the trial ended, Mencken ignored the admonition to avoid speaking ill of the dead, with devastating effect:

It was hard to believe, watching him at Dayton, that he had traveled, that he had been received in civilized societies, that he had been a high officer of state. He seemed only a poor clod like those around him, deluded by a childish theology, full of an almost pathological hatred of all learning, all human dignity, all beauty, all fine and noble things. He was a peasant come home to the dung-pile. Imagine a gentleman, and you have imagined everything that he was not.

Mencken was about as close as anyone could come to a First Amendment absolutist. He waged a high-profile battle against the New England Watch and Ward Society and risked his livelihood and his freedom in 1926 fighting a ban on The American Mercury over a short story by Herbert Asbury about a prostitute called “Hatrack,” who serviced her Catholic clients in the Masonic cemetery and her Protestant clients in the Catholic cemetery. Mencken won, but at considerable expense. And yet, even though he supported Theodore Dreiser’s right in theory to stage his notorious play, “The Hand of the Potter,” which featured centrally an act of rape and murder of a child, he admonished Dreiser that it was not a fight worth waging.

“I daresay you will accuse me of a lingering prudishness,” Mencken wrote in a 1916 letter. “Accuse all you please; it is not so.” He went on:

If the thing were possible, I’d advocate absolutely unlimited freedom in speech, written and spoken. I think the world would be better off if I could tell a strange woman, met at a church social, that I have diarrhoea—if the stage could be used to set up a more humane attitude toward sexual perverts, who are helpless and unhappy folks—if novels and other books could describe the precise process of reproduction, beginning with the hand-shake and ending with lactation, and so show the young what a bore it is. But these things are forbidden. The overwhelming weight of opinion is against them. The man who fights for them is as absurd as the man who fights for the right to walk down Broadway naked, and with his gospel pipe in his hand. Both waste themselves upon futile things while sound and valuable things remain to be done.

Mencken had no patience for communism. Of liberals, he observed, “they seem to be quite unaware that their opponents have rights.” As much as Mencken distrusted government “by the people,” he understood that the progressive enthusiasm of government “by the experts”—which is what contemporary pundits mean by “Our Democracy”—was no better.

In an indirect way, his violent criticism of Southern culture—captured in his famous essay, “The Sahara of the Bozart”—inspired the Southern Agrarians, whom he also thought lacked the foresight and nerve to “grapple with things as they are.” (Though, as historian Fred Hobson observes, Mencken failed to acknowledge where the Agrarians aligned with his own thinking, such as their shared disdain for “the Gospel of Progress” and “the Gospel of Service.”)

Mencken may be remembered best for his

volleys against the New Deal, which led to a sharp decline in his popularity in the 1930s. He didn’t seem to mind. “If it is a fact that I am doomed to go unheeded, then I don’t care a damn,” he wrote in an autobiographical note. “I write because I like it, not because I want to convert anyone.” Less known is his early support for Franklin Roosevelt. In 1932, Mencken lauded FDR in the Sun as “the most charming of men,” and said he would happily give Roosevelt his vote if only to “get rid of Hoover.” His attitude changed quickly in 1933, as the New Deal began to take shape.

Mencken recognized at once what Roosevelt’s policies meant. The New Deal “had only one new and genuinely novel idea: whatever A earns really belongs to B. A is any honest and industrious man or woman. B is any drone or jackass.” He watched with horror as Congress ceded Roosevelt unprecedented powers. His fury against Roosevelt was only heightened by his belief that his colleagues were failing in their duty to “keep a wary eye on the gentlemen who operate this great nation, and only too often slip into the assumption that they own it.”

“Keep a wary eye on the gentlemen who run this great nation, and only too often slip into the assumption that they own it.”

By 1936, Mencken had publicly announced his support for Republican Alf Landon, even though he believed his campaign was likely doomed and later described it as a “funeral procession.” He maintained his attacks on Roosevelt over the next four years, even as his audience turned away from him and it appeared likely that the United States would enter another disastrous war.

If Mencken’s efforts to sway public opinion against Roosevelt ultimately fell short, it was not for lack of trying. In a 1937 memo to the Sun’s owner and publisher, Paul Patterson, Mencken argued for maintaining a rigorous editorial independence even in the face of official pressure:

I do not propose that we denounce the Administration incessantly and unreasonably. I only propose that we view it skeptically, and refuse to assent to its devices and pretensions until we are sure that they are intelligent and sincere. Every public official with large powers in his hands should be held in suspicion until he proves his case, and we should keep him at all times in a glare of light.

But by 1939, Patterson had come to agree with Sun Managing Editor John W. Owens’ “wholly pro-English view of the international situation.” Patterson’s chief concern, Mencken wrote in his diary on Oct. 6, 1939, “is to maintain the prosperity of the property. My own is quite different. I believe, and I told him, that the imbecile arguments concocted and printed by Owens were doing the people enormous damage.”

“Roosevelt is a fraud from snout to tail,” Mencken wrote. “Every one in Washington is well aware that he is itching to get the United States into the war. For the Sun to ignore or attempt to conceal that fact involves an abandonment of integrity that seems to me highly dangerous.”

Roosevelt cruised to a third reelection in 1940, crushing Republican businessman Wendell Wilkie by 5 million votes, carrying 38 of 48 states, and winning 449 electoral votes to Wilkie’s 82. Part of the problem, Mencken explained in his Monday column a week after the election, is that Willkie often sounded indistinguishable from the man he sought to replace in the White House. “It is impossible to beat a demagogue by swallowing four-fifths of his buncombe, and then trying to alarm the boobs over what little that is left,” he wrote. “The truth is that Wilkie swallowed rather more than four-fifths. He went along on each and every one of the New Deal schemes to uplift the downtrodden and bring in Utopia at home, and he went along in the large and hearty way on the New Deal scheme to succor ‘morality and religion’ abroad.”

Privately, he regarded FDR’s third victory in 1940 as a bona fide catastrophe. “I begin to believe seriously that the American Republic as we were taught to know it blew up last night,” Mencken wrote to Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., on Nov. 6. “The forms, to be sure, will survive for a little while, but the substance is all gone…. My belief is that democracy is fading out of the world. It was unquestionably a more or less noble experiment, but it simply failed to work.”

Driven from writing on politics full-time by the wartime censorship regime and the Sun’s willingness to embrace it, Mencken turned his energies and attention to his memoirs—the Days trilogy (Happy Days, Newspaper Days, and Heathen Days), which began as lengthy reminiscences in The New Yorker—and two supplements to The American Language, along with two autobiographical works that would remain under lock-and-key for 35 years after his death, Thirty-five Years of Newspaper Work and My Life as Author and Editor.

He continued to quarrel with his Sun colleagues over the paper’s stance on the war in Europe. By January 1941, Mencken had had enough and planned to resign his position as columnist. He met with Patterson, who practically begged him to stay. If he was going to give up writing, Patterson pleaded, then he could at least remain on as a “news-consultant.” Mencken agreed, but at half salary. His final contribution to the Sunday Sun’s opinion page appeared on Feb. 2, 1941. It was, true to form, a final public denunciation of Franklin D. Roosevelt, warmonger.

Mencken was made for print. Born on Sept. 12, 1880, to a solidly middle class family, his childhood and adolescence were saturated with books and magazines—Mark Twain above all. The age of television and the Internet would not have equipped him to write as much as he did, in the way that he did, for today’s post-literate audience, which is more likely to spend hours a day distracted by two-minute videos of automobile accidents, stunts gone wrong, cat antics, and toddlers lisping obscenities to the delight and horror of their parents.

His output was incredible. In his preface to his 1948 collection, A Mencken Chrestomathy, Mencken hazarded a guess at his total production. “What the total of my published writings comes to I don’t know precisely, but certainly it must run well beyond 5,000,000 words. A good deal of it, of course, was journalism pure and simple—dead almost before the ink which printed it was dry.” Rodgers, in her editorial note to The Impossible H.L. Mencken, surmised he wrote more than 3,000 articles for the Sun and other newspapers, including The Chicago Tribune and the New York Morning Herald, over the decades. He wrote hundreds of reviews and editorials for The Smart Set and The American Mercury. And that doesn’t count his prodigious correspondence, which ran into the hundreds of thousands of words.

Mencken frequently reworked his newspaper columns for magazines and, later on, his books. Often his columns formed the basis for some of his most important and enduring works. The American Language, which appeared in four editions between 1919 and 1936 and included two fat supplements totaling some 2,200 pages, began in 1910 as a column for the Baltimore Evening Sun titled “The Two Englishes.”

In his younger days, it was not unheard of for Mencken to write 5,000 words a day or more. Mencken’s “Free Lance” columns appeared in the Sun five days a week from 1911 to 1915. Monday columns, which appeared from 1920 to 1938, often ran over 1,000 words. Such numbers are only astounding because few professionals could pull them off in an age of distraction. The Internet would have suffocated Mencken, just as it has suffocated an untold number of writers of far lesser talent and an order of magnitude more readers.

The slackening of the American mind was already evident in Mencken’s prime but accelerated during his twilight years. He came out of semi-retirement in 1948 to cover the Republican, Democratic, and Progressive Party conventions—the first year the events were broadcast on the new medium of television.

But even before TV took over Americans’ homes, Mencken routinely excoriated their excess affection for radio, which he thought offered not much more than mindless entertainment and propaganda. This was also a man who hated the telephone. “Having suffered under it for forty years,” he told one correspondent, “I should be more or less used to it by now, but the plain fact is that I jump every time it rings.” “The telephone is undoubtedly the most valuable of American inventions,” he wrote in The Chicago Tribune in 1937. “It is worth a dozen airplanes, radios, and talking machines; it ranks perhaps with … gin, the movie, and the bichloride tablet. But here again, once more and doubly damned, we become slaves to a machine. What I propose is simply a war of liberation.”

Now try to imagine H. L. Mencken with a smart phone. Impossible!

Mencken was arguably one of the first targets of “cancel culture.” He recognized its primitive form over a century ago, after the outbreak of World War I, when public dissent was often brutally suppressed and expressing pro-German sentiment invited personal and professional ruin.

Even before his controversial diary saw the light of day in 1989, he was the subject of savage appraisals from his many critics and some friends-turned-adversaries. Carl Van Doren assessed the Sage of Baltimore as one who “most conspicuously lacks … the mood of pity.” Charles Angoff, his former assistant who held strong communist sympathies, published a scandalous book-length calumny against his one-time mentor less than five months after Mencken’s death in January 1956. To read Angoff is to get the sense of a man utterly incapable of taking a joke. But he was also among the earliest biographers to accuse Mencken of racism, anti-Semitism, and pro-Nazi sympathies.

Those charges would reemerge with gusto with the publication of Mencken’s diary 33 years later, from journalists who never knew the man and who knew practically nothing of his work. By today’s impossible standards, of course, Mencken must be judged a bigot and a racist. But these charges are overblown, if not libelous. Mencken certainly used language in his private papers that made the allegations plausible. But his deeds were anything but bigoted, anti-Semitic, or supportive of Hitlerism.

Latter-day critics confuse words with deeds. This was an editor who launched the career of George S. Schuyler, championed the Harlem Renaissance in the pages of the American Mercury, and inspired Richard Wright to become a novelist and activist. He published and touted black writers such as Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Claude McKay, and Walter F. White, who went on to lead the NAACP. In fact, Mencken encouraged White to write a novel on race relations in the South and helped get it published. This was also a man who was lifelong friends with Alfred and Blanche Knopf, and whose business partner for 15 years was George Jean Nathan. Though he was not enthusiastic about the United States accepting Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany, and said so in print, behind the scenes he helped at least a dozen Jews and their families leave that country at his own expense.

But it’s also true that Mencken also referred to blacks as “darkies,” “blackamoors,” and occasionally even “coons,” and called some Jews “kikes.” Every educated person nowadays, of course, knows that “words are violence.”

There is some irony in the fact that Mencken’s final column before his stroke on Nov. 23, 1948, which deprived him of the ability to read and write, was headlined, “Mencken Calls Tennis Order Silly, Nefarious.” In it, he criticized the segregation of public tennis courts. “It is high time that all such relics of Ku Kluxry be wiped out in Maryland,” he wrote. “The position of the colored people … has been gradually improving in the State, and it has already reached a point surpassed by few other states. But there is still plenty of room for further advances, and it is irritating indeed to see one of them blocked by silly Dogberrys. The Park Board rule is irrational and nefarious. It should be got rid of forthwith.”

But those were mere words, and hardly an apology. He could never be redeemed in the eyes of his critics, who only see through the lens of race and sex. Though it’s impossible to think, had he lived past 1956, that he would have joined hands and marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma, it isn’t hard to imagine that he would have showed up from Baltimore to cover King’s “March on Washington” in 1963 at the ripe old age of 83 and written sympathetically about the cause of civil rights.

In another context, Mencken pegged the cancel mob’s mentality exactly: “Only one interpretation is possible. No exculpatory evidence is admissible. No righteous deeds could possibly mitigate the offense.”

The Sun’s editorial page nobly stood by their greatest writer in the wake of the diary’s publication in 1989. By 2020 and the “Summer of Floyd,” however, Mencken was impossible to defend in the Sun’s pages. In February 2022, the Sun published a 4,400-word editorial headlined, “We are deeply and profoundly sorry: For decades, The Baltimore Sun promoted policies that oppressed Black Marylanders; we are working to make amends.” The ritual self-flagellation that followed reviewed more than 185 years of the newspaper’s history. Very little survived the editorial board’s woke view of the past. “Through its news coverage and editorial opinions, The Sun sharpened, preserved and furthered the structural racism that still subjugates Black Marylanders in our communities today,” the editors wrote.

Mencken, of course, came in for a harsh denunciation. It wasn’t enough that he wrote some of the sharpest attacks on lynching in the 1930s, at some personal risk, and even testified before Congress in support of federal anti-lynching laws. The trouble was Mencken’s “ire was directed at the ‘poor, white trash’ killers…; there was no empathy for—or even real interest in—the Black victims.”

Oddly, the Sun’s editorial neglected to mention perhaps the most damning piece of evidence against Mencken and his contemporaries. In 1919, Mencken and Harry Black, a prominent stockholder of the Sun, wrote a memorandum outlining how to make the publication a “nationally distinctive newspaper.” It became known as “The White Paper”—a nickname that would surely excite critical race theorists across the land. The memo was devoted largely to laying out principles that would ensure the Sun would remain “absolutely free” from “any steady fidelity to either political party.” So far, so good.

But here’s where Mencken condemns himself in the light of present-day sensibilities: “Here we have an important and a living issue in the question of the Negro in his part in our politics, and the two parties are still clearly separated upon it. On this question, the Sun can take but one position. As between the black man and the white man, it must be in favour of the white man. Thus the Sun will find itself in the Democratic camp so long as the Democrats view this issue as they do now.”

A quote of Mencken’s had appeared on the wall of the Sun’s lobby, “showing, in the most generous interpretation, a lack of self-awareness and sensitivity,” the paper’s editors wrote. When the Sun relocated to more modest facilities in 2018, the Mencken quote did not survive the move. Instead, one wall was covered with a photo from a Black Lives Matter protest. “It’s a better reminder of what we are here to do than the Mencken quote for various reasons, not the least of which is that it’s about the people we serve, rather than about us… Actions speak louder than words, even in the newspaper business.” Sixty-five years after the old man’s death, you could almost hear him chuckle.

Mencken was not stranger to charges of racism in his lifetime. “It doesn’t matter what they think of me,” he told biographer William Manchester in response to his critics. “My work will depend, not on what those people think of me, but on what I’ve done.”

And as an author, an editor, a social critic, and a newspaperman, he did vastly more than any third-rate, woke editorial writer could hope to accomplish. He did the impossible.

Leave a Reply