Historians of the American right agree that Russell Kirk (1918-1994) was one of the key figures in the birth of the postwar conservative movement. Indeed, Kirk more than anyone was responsible for reintroducing the term “conservative” into American political conversation after its long domination by various strands of liberalism. The centenary of his birth in 2018 occasioned a welcome renewal of interest in his writings after decades of comparative neglect.

The story of how a 35-year-old Kirk burst onto the cultural and political scene with the publication of The Conservative Mind: Reflections from Burke to Santayana (1953) is familiar to many. Kirk’s six “canons of conservatism” and the profiles of major figures in Anglo-American history whose work exemplified those canons were immensely influential, helping to reorient the American right away from a Hayekian emphasis on individualism and free markets. Kirk praised the particular over the abstract universal, tradition over needless innovation, and private property over collective ownership. Conservatism, he wrote, is the negation of ideological thinking (communist, fascist, utilitarian, or any other kind), which threatens to dehumanize and regiment society.

The success of The Conservative Mind enabled Kirk to resign his faculty position at Michigan State—he had already begun to decry the industrializing and dumbing-down of higher education—and take up residence in his ancestral home in the village of Mecosta in central Michigan. There he tended aging members of his extended family and established a career as an “independent man of letters.”

Few scholars have enjoyed as productive a decade as Kirk did between 1953 and 1963. Books, articles, short stories, essays, and reviews poured forth from his typewriter with remarkable speed. During this period, Kirk also founded the journals Modern Age and The University Bookman, both of which are still in publication.

One anecdote about Kirk’s productivity will have to suffice. In 1954, a 28-year-old William F. Buckley Jr. traveled to Mecosta with the hope of recruiting the now-famous scholar to contribute regularly to National Review, then still in its planning stages. Buckley later recalled that after agreeing to write for the magazine, Kirk drank him under the table, deposited him in the guest room, and spent the night writing a chapter of a monograph on St. Andrews, the Scottish town where he had completed his doctoral studies. When Buckley emerged, bleary-eyed, the next morning, Kirk made him breakfast before heading off to grab a few hours of sleep himself.

Kirk taught conservatives about the need to engage the culture on levels other than those of law and politics. In A Program for Conservatives (1954), he identified ten “problems” for conservatives to confront; most of them had little or nothing to do with politics. Social boredom, wants, the mind, the heart—these are core concerns not normally addressed in public policy manuals, but Kirk insisted that the conservative must speak to each of them.

Many of Kirk’s own cultural contributions came in the field of imaginative literature. In three novels and 22 short stories dating mostly from the 1950s and 1960s, Kirk demonstrated a capacity to affect readers in a way most policy wonks can only imagine, while still articulating a morally and aesthetically conservative vision. His most successful novel, The Old House of Fear (1961), was a gothic thriller. It garnered accolades from The New York Times and other publications and became a featured title for organizations like the American Library Association. It also sold more copies than all of Kirk’s other books put together.

Kirk believed that his “preternatural” tales could be powerful vehicles for the moral imagination, and thus influence many thousands of readers who would never pick up a political treatise. He understood that literature and the arts are an essential arena where conservatives must establish themselves.

Kirk’s scholarly and literary output diminished after he married Annette Courtemanche in 1964—the couple produced four daughters in due course—but he continued to write magisterial works well into the 1970s on topics such as T. S. Eliot and the American founding.

Kirk’s experiences late in life were a microcosm of what was happening to the traditionalist right as a whole. He received respect as a sort of elder statesman of the conservative movement, but neoconservatives and careerists worked to deny him real influence during the Reagan/Bush years. Most unforgivable in their eyes was Kirk’s criticism of America’s adventurous foreign policy on behalf of Israel.

He articulated this view at length in lectures delivered at the Heritage Foundation, and endured, as a result, the inevitable charges of anti-Semitism. Privately, he alleged that prominent neoconservatives had denied him recognition in Washington. Kirk labeled the 1991 Gulf War a “war for an oil-can” and campaigned for Patrick Buchanan against Bush in 1992. Although Kirk never owned the “paleoconservative” label, he clearly had more in common with that group of writers than he did with what had become mainstream conservatism by the end of his life.

He articulated this view at length in lectures delivered at the Heritage Foundation, and endured, as a result, the inevitable charges of anti-Semitism. Privately, he alleged that prominent neoconservatives had denied him recognition in Washington. Kirk labeled the 1991 Gulf War a “war for an oil-can” and campaigned for Patrick Buchanan against Bush in 1992. Although Kirk never owned the “paleoconservative” label, he clearly had more in common with that group of writers than he did with what had become mainstream conservatism by the end of his life.

Kirk sparred with libertarians throughout his career, most famously calling them “chirping sectaries” in a 1981 Modern Age article. Years later he asserted that libertarianism was no more compatible with conservatism than was communism. This antipathy seems curious because Kirk agreed with libertarians in his desire to shrink the state far beyond the point many other traditionalist thinkers were willing to countenance.

Like Robert Nisbet, recently described in these pages as a “traditionalist libertarian,” Kirk endorsed a “new philosophy of laissez-faire” centered on local associations rather than the individual. He was skeptical of many “pro-family” policies floated in Washington. For example, when the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops recommended increases in subsidies for day care programs, Kirk retorted that American families would be better off if their taxes were cut to a level that would allow mothers to stay home with their children.

Nevertheless, Kirk rejected the fusionist project of fellow National Review contributor Frank Meyer and consistently warned against conservatives making common cause with libertarians.

When one reads Kirk’s criticisms of libertarians more closely, two points stand out. First, Kirk viewed libertarians as a species of leftist. Their representative figure was John Stuart Mill, whose “harm principle” is an oversimplification of reality, one that cannot suffice to govern men. Second, he excluded from this leftist characterization those self-identified libertarians who valued traditional mores and culture; such libertarians, he wrote, are simply conservatives with an imperfect understanding of political terminology. Murray Rothbard and other writers disputed the justice of these assertions, but Kirk never wavered in his belief that conservatives and libertarians could affirm nothing in common. To him, ideology was the problem.

With the meaning of “conservatism” seemingly up for grabs once again as we enter the third decade of the 21st century, the right would do well to revisit the work of the “sage of Mecosta.” Would Kirk embrace the insurgent populism that some claim has resulted in a “hostile” takeover of the Republican party? Or would he count himself amongst the anti-Trump conservative rump?

The latter possibility would not be likely. Kirk’s embrace of the Buchananite bid for the presidency, his oft-repeated criticism of “free trade” deals like NAFTA, his concern that an open borders policy would threaten the cohesion and economic stability of the American heartland, his opposition to interventionism abroad—all of these positions suggest that he would be largely supportive of the key planks in the Trump platform. Yet it is also likely that Kirk would regard much of Trump’s populist appeal as a dangerously shallow nationalism, one that is largely clueless as to what constitutes American “greatness.”

Will “conservatism” find its way when the current populist unrest ebbs? Will it counter the anti-American radicalism that dominates the Democratic Party and much of the intelligentsia? Kirk understood, as many today do not, that resisting the ideological temptation and engaging culture on a broad front are essential to a future conservatism that is true to its principles.

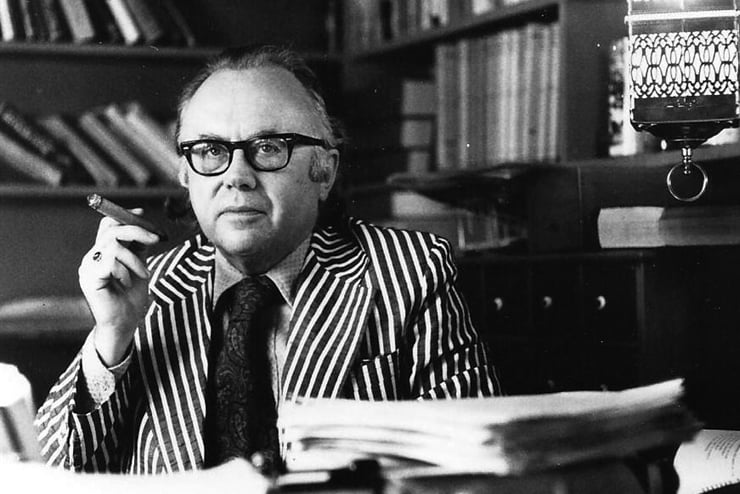

Image Credit:

above: Russell Kirk in his library at Mecosta, Michigan, the typescript of Roots of American Order stacked before him (image courtesy of The Russell Kirk Center)

Leave a Reply