The Reactionary Aesthete

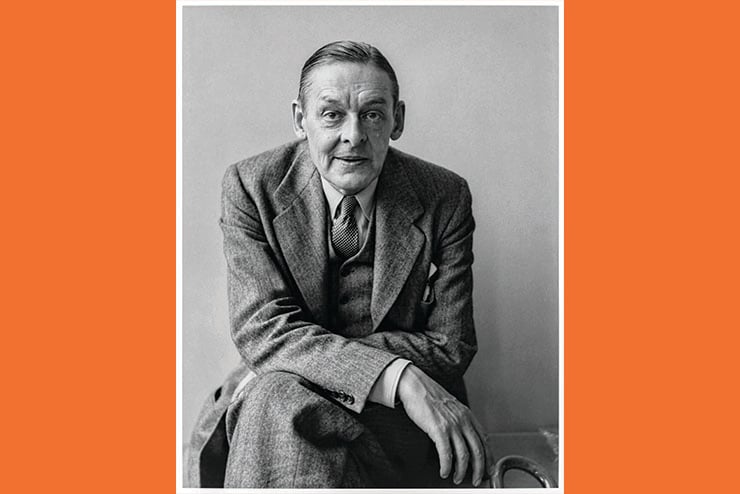

Friends and foes of poet and critic T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) have commonly understood him as a traditionalist par excellence—either the 20th century’s greatest traditionalist or its most lamentable one, depending on one’s view. For friends, he was a Burkean conservative who defended the “moral imagination” of high art and who disdained what he referred to in a memo as the “Surrealist racket.” For foes, he was a reactionary who lacked either the courage or constitution to write further experimental verse after he published the century’s most famous experimental poem, “The Waste Land” (1922), and retreated instead to his office at the publishing firm Faber & Faber, where he made grandiose, self-serving statements about the function of literature.

The novelist Cynthia Ozick expressed this second view in unusually blunt terms in a 1989 New Yorker essay, “T. S. Eliot at 101.” She wrote that Eliot was nothing more than “an autocratic, inhibited, depressed, rather narrow-minded, and considerably bigoted fake Englishman,” whose ideas caught on “temporarily” in America but were quickly replaced “by the formation of natural tissue.” Eliot had abandoned America to become the high priest of an abstract pan-European culture and an enemy of “democracy, tolerance, and individualism.” She concluded that his influence had waned considerably since he died, and should wane further still.

The real Eliot—the Eliot that is worth remembering—was nothing like Ozick’s caricature. He was certainly guilty of the occasional ex-cathedra pronouncement, but to read him at length is to encounter a nuanced mind at work. He defended both the idea of a Christian society and the necessity of the free exercise of religion within that same society. He may have been a member of the cosmopolitan elite, but he argued that all culture was local and had a soft spot for ragtime and vaudeville. He was a traditionalist, no doubt, but a traditionalist who was also an aesthete, one who defended the independence of art and lauded the highly individualistic work of poets like David Jones and the now mostly forgotten John Gould Fletcher, among others.

But Eliot’s influence had waned by 1989, and it has waned further still. Only a handful of poets and critics claim him as an influence today. Other than his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919) and “The Waste Land,” much of his work goes unread. The publication of nearly all of his letters (which is still underway), his complete prose (2021), and a new two-volume edition of his poetry (2018) have done little, it seems, to re-establish his importance. Yet, he saw with clarity what a society devoted to freedom as an end in itself would become, and he was an astute critic of secularism and the reduction of art to a political tool that has become so widespread today.

Born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, Eliot was a descendant of the wealthy and influential Massachusetts family that included Charles Eliot Norton, the Harvard art professor renowned in the 19th century as liberal activist and social reformer. Eliot graduated from Harvard in 1909 and spent a year in France before returning to Massachusetts to do doctoral work in philosophy. He was in Germany on a travel fellowship when war broke out. He was able to make it to England on Aug. 20, 1914, where he would spend the rest of his life, returning only infrequently to the United States. Eliot worked briefly at Lloyds Bank in London before becoming in 1925 the editorial director at what was then the publisher Faber & Gwyer. His two most influential poetry collections were The Waste Land and Four Quartets (1943). His 1935 play “Murder in the Cathedral” was an international success. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948.

Eliot’s poetry can be understood as an act of recovery. In early poems, he inventories modern man’s reduced state in a world where, as he puts it in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (1915), there is “no great matter” and language has become a string of empty “formulated phrase[s].” Modern men are “stuffed men,” Eliot wrote in “The Hollow Men” (1925), whose heads are “filled with straw”:

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

In “The Waste Land,” the poet rummages through Western culture’s “heap of broken images” to see if the “fragments” still contain any power. The poem ends with the Sanskrit chant from the Upanishads, “Shantih shantih shantih,” meaning “Peace peace peace,” but Eliot wrote in his notes to the poem that the repeated phrase is the equivalent of “Peace which passeth understanding.” In “Little Gidding” from Four Quartets, Eliot suggests that only a divine being can vivify our words and give time—and human action—meaning. “The dove descending breaks the air,” Eliot wrote,

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The one discharge from sin and error.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre—

To be redeemed from fire by fire.

Eliot’s two overarching concerns in his prose were the characteristics of a flourishing culture and the function of poetry and criticism. In his “Notes Towards the Definition of Culture” (1949), Eliot argued that all culture is grown “from the soil” and cannot be created arbitrarily “by any activity of political demagogues.” Culture, Eliot continued, is “the one thing that we cannot deliberately aim at.” It is the product, rather, of “a variety of more or less harmonious activities, each pursued for its own sake.”

By “culture,” Eliot means “all the characteristic activities … of a people,” not just high culture. These activities develop from religious beliefs. No culture, he wrote, “can appear or develop except in relation to a religion.”

In other words, Eliot means that all aspects of a culture develop from a group’s beliefs about themselves and the world—not what they say they believe, but what they actually believe. Whether we refer to things like “a cup final, the dog races, … boiled cabbage cut in sections” or Paradise Lost, culture is “our lived religion.”

In The Idea of a Christian Society (1939), Eliot defines liberalism as a movement “away from, rather than towards, something definite,” which can never create a flourishing culture. While Eliot admits that liberalism is a “necessary negative element” of any functioning society, if this movement is understood as an unequivocal good, it leads to chaos and perhaps even totalitarianism:

By destroying traditional social habits of the people, by dissolving their natural collective consciousness into individual constituents, by licensing the opinions of the most foolish, by substituting instruction for education, by encouraging cleverness rather than wisdom, the upstart rather than the qualified … Liberalism can prepare the way for that which is its own negation: the artificial, mechanized or brutalised control which is a desperate remedy for its chaos.

In contrast, a “positive culture” requires “a positive set of values,” and Eliot argued that Christianity provides a foundation for those things, which are necessary for the development of a highly developed culture. These values include the importance of truth, a high view of tradition and excellence, an appreciation for hierarchy rightly understood, and an anti-materialist understanding of life.

Eliot did not argue that a Christian society be composed of only Christians or that individuals be forced to convert. It simply means that everyone would receive a Christian education, which is to say, they would be trained “to be able to think in Christian categories,” whatever their personal beliefs, and that policy debates would take place within “a Christian frame.”

In fact, one of Eliot’s important but often ignored remarks concerning culture is his defense of differences within cultures and the importance of diversity, rightly understood. In “Notes,” Eliot wrote that both an excess of “unity” and an excess of “division” prevent a culture from developing. “Neither a classless society, nor a society of strict and impenetrable social barriers is good,” he wrote.

Eliot argued, like Christopher Lasch later would in The Revolt of the Elites (1994), that it is important for social classes to “mix freely” and to share a common culture. Friction within a culture is not all bad; “within limits,” it leads to both “creativeness and progress.” A “uniform culture,” on the other hand, is “no culture at all,” he wrote, because it suppresses the diversity that would otherwise occur naturally within a human society. A uniform culture requires a “humanity de-humanised.”

Eliot also argued that great cultures develop in part through the exchange of ideas and the nondisruptive movement of peoples to other lands. “The notion of a purely self-contained European culture,” Eliot wrote, “would be as fatal as the notion of a self-contained national culture.”

No one nation, no one language, would have achieved what it has, if the same art had not been cultivated in neighboring countries and in different languages. We cannot understand any one European literature without knowing a good deal about the others. When we examine the history of poetry in Europe, we find a tissue of influences woven to and fro.

It is doubtful, however, that Eliot would have seen the current waves of non-European mass migration to Europe and America as nondisruptive.

Eliot remained remarkably consistent in his view of the function of poetry and criticism from his earliest statements on the subject in 1923 to his final, formal remarks in 1956. He rejected the idea—so common today—that criticism is an end in itself. In “The Function of Criticism,” Eliot wrote that “criticism must always profess an end in view, which roughly speaking, appears to be the elucidation of works of art and the correction of taste.”

Eliot didn’t mean the critic should limit himself to the literary text alone. To “elucidate” the text, a critic must establish certain “facts” about the work—“its conditions, its setting, its genesis”—but these are always in the service of the analysis of the text. He would have rejected the recent trends in literary criticism that put the author’s racial, sexual, or cultural identity first and foremost.

By “analysis,” Eliot doesn’t mean “interpretation,” which, he remarks, always leads the critic to produce “parts of the body” of a work of literature from his “pockets” and fixing them to it. In other words, explaining the meaning of a work of art always adds something to it.

Analysis is instead a comparative observation. In his 1932 and 1933 Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Eliot remarks that analysis is simply the assessment of “actual poetry.” In those lectures, he pushes back against what he calls the “psychological and sociological … varieties of modern criticism.” While Eliot admits that poetry communicates all sorts of things, including psychological and sociological states of affairs, what it communicates as a poem “is the poem itself.” When a critic falls into the error of divining the poet’s intention in making certain formal choices, he is trafficking in mere speculation:

That there is a relation (not necessarily noetic, perhaps merely psychological) between mysticism and some kinds of poetry, or some of the kinds of state in which poetry is produced, I make no doubt. But I prefer not to define, or test, poetry by means of speculations about its origins; you cannot find a sure test for poetry, a test by which you may distinguish between poetry and mere good verse, by reference to its putative antecedents in the mind of the poet.

Eliot does not deny the importance of the meaning of words in a poem and the role the relative truth of those words plays in the aesthetic experience. But he repeatedly argues that the first “function of poetry” is “to give pleasure.” In “The Social Function of Poetry,” he wrote, “If you ask what kind of pleasure, then I can only answer, the kind of pleasure that poetry gives.”

Immediately after this, Eliot remarks that the pleasure of poetry is not “only pleasure,” by which he means that it is not only a formal or audio pleasure. That would make poetry into architecture or music. If “it were only pleasure,” he wrote, “the pleasure itself could not be of the highest kind.” There is always, he continued, “the communication of some new experience, or some fresh understanding of the familiar.”

In his essay “The Music of Poetry” (1942), Eliot notes how the music of poetry “is latent in the common speech of its time.” The “communication” of the poem, or the experience of the poem, is found in the twofold experience of words as signs and as music. This is why poetry can “convey something beyond what can be conveyed in prose rhythms.” In “The Frontiers of Criticism” (1956), he wrote, “I do not think of enjoyment and understanding as distinctive activities—one emotional and the other intellectual.” He continued, “To understand a poem, comes to the same thing as to enjoy it for the right reasons.”

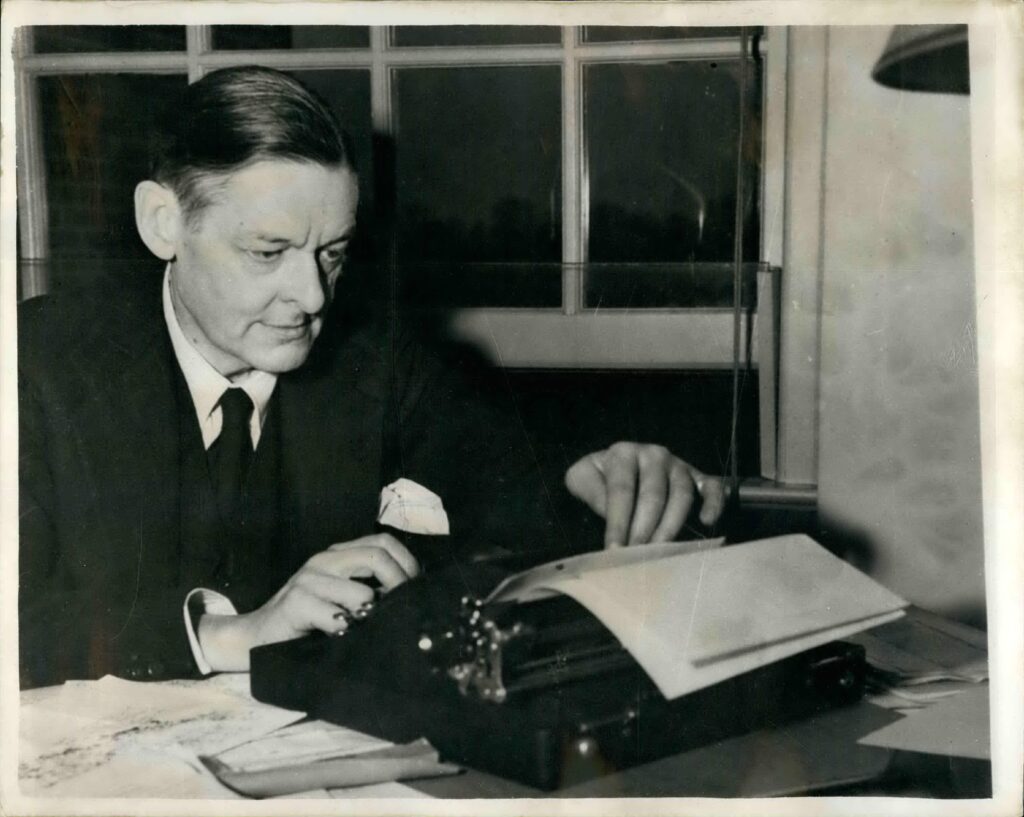

(Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo)

The point, as Eliot notes in his Norton Lectures, is that a critic should evaluate a poem as a poem, not as a mere expression of a poet’s state of mind or the social situation in which it was written. The critic’s task is not to evaluate the poem’s political or “moral and educational value.”

“Morals for the saint are only a preliminary matter; for the poet a secondary matter,” Eliot wrote. His point is that the task of the critic is to make an aesthetic judgment because a poem is first and foremost an aesthetic rather than a political or moral document:

The doctrine of “art for art’s sake,” a mistaken one, and more advertised than practised, contained this true impulse behind it, that it is a recognition of the error of the poet’s trying to do other people’s work.

Eliot concludes his Norton Lectures by stating, “Poetry begins … with a savage beating a drum in a jungle” and “retains that essential of percussion and rhythm.” It is “not to be defined by its uses.”

If it commemorates a public occasion, or celebrates a festival, or decorates a religious rite, or amuses a crowd, so much the better. It may effect revolutions in sensibility such as are periodically needed; may help to break up the conventional modes of perception and valuation which are perpetually forming, and make people see the world afresh, or some new part of it. It may make us from time to time a little more aware of the deeper, unnamed feelings which form the substratum of our being, to which we rarely penetrate… But to say all this is only to say what you know already, if you have felt poetry and thought about your feelings.

We live in an age that speaks of poetry only in terms of its uses. Eliot reminds us that what it does is simply exist, which is a testament of our humanity.

Leave a Reply