Guardian of Authority

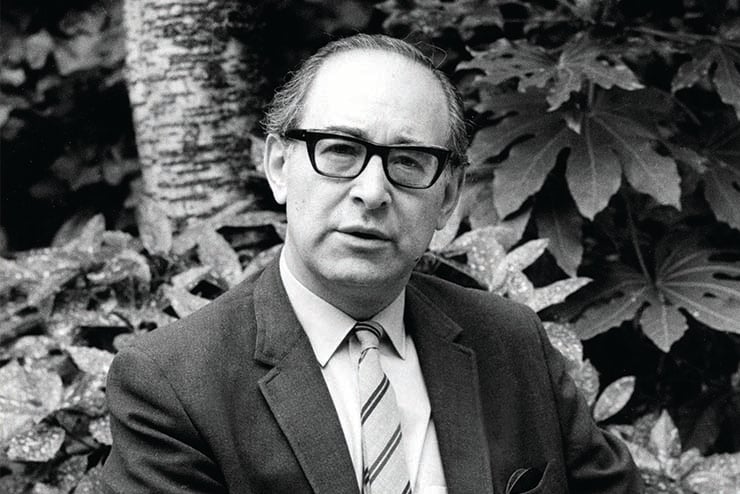

It is a commentary on the banality of American conservatism today that Thomas Molnar, a towering figure on the American intellectual scene in the second half of the 20th century, has now disappeared down the democratic memory hole.

Molnar did not found a school of thought, nor was he a “fusionist.” He was, toward the end of his life, increasingly anti-American, in the sense that he began to view the American political project, at least in its modern development, as profoundly subversive of the inequality necessary for the transmission of enduring authority. He was a theologian, a philosopher, a political thinker, and a historian of ideas—particularly of the history of utopian thought in the West.

While Molnar admired aspects of the American conservative tradition, he was at heart a Catholic royalist and a reactionary in the French tradition of Joseph de Maistre, Charles Maurras, Georges Bernanos, and Jean Raspail. At the heart of his work was the problem of authority and how it might be sustained in a world where power had been shorn of its sacral dimension.

Born in Budapest in 1921 to Catholic parents, Molnar began his undergraduate studies in Brussels in 1940, where he quickly became a leader in the Catholic student resistance movement. He drew the attention of the Nazi authorities, resulting in his removal to the concentration camp in Dachau, Germany, in 1944. Upon his release at the end of World War II, he returned briefly to Hungary, in time to witness its occupation by Soviet forces. He was lucky enough to emigrate to the U.S., where he completed his Ph.D. in philosophy at Columbia in 1950.

For some years, Molnar taught French and European literature at Brooklyn College, followed by a professorship at Long Island University. During this time, he met and married his wife, Ildiko—a widow of Hungarian birth—and began to publish in several conservative journals, including National Review, Commonweal, Modern Age, and Triumph. It was also during this period that he was befriended by Russell Kirk (whose The Conservative Mind he admired). In the late 1960s, he and his family settled in Richmond, Virginia. After the fall of the Communist regime in Hungary in 1989, Molnar taught for a part of each year at the University of Budapest.

The influence of the French reactionary tradition is markedly evident in Molnar’s 1976 book Authority and its Enemies. In that book, he argued forcefully that the principle of authority in society must always be subordinated to a higher law, specifically natural law, and must be mediated by strong institutions. These institutions should be controlled by an elite class thoroughly schooled in the limits of its authority. Lacking such institutions, he wrote,

the words and acts of officials (magistrates) are not mediated to society with sufficient clarity and persuasion. The situation is, then, one of anarchy as we see it around us today, or despotism when the officials use naked power, scorning the mediation role of institutions.

In this text, he frequently argued that the authority to which the social, legal, and political order is subordinate must be one that “appeals to the moral intelligence.” Such authority must be wielded with the “right moral perception and the political will to translate it into solid institutions.” But right moral perceptions, he asserted, have in Western societies been systematically blunted, and the anarchistic strain, especially in America, has become more pronounced. (Think of the popular American slogan “Question Authority”—as if the very concept of authority were inherently suspect.) Thus, the “enemies of authority have managed to widen … the gap between legitimate authority and what remains feasible under current circumstances.” Moreover, he wrote, we are all too often instructed that what we call authority is merely an evolutionary reflex, a projection of the “primitive superego.”

Much of the blame for the dissolution of the traditional sources of authority can be attributed to the emergence of the figure of the “intellectual” in the early Renaissance. In The Decline of the Intellectual (1961), a text that became one of Molnar’s best-known works among American conservatives, he argued that as the social cohesiveness of the European Middle Ages began to wane, a new class of men acquired widespread influence. They were often peripatetic humanists and political advisors to kings, men who in an earlier age might have been philosophers or scholars but who were now wedded to the centers of power and sought the “transformation of society.”

The boldest among these were, like Niccolo Machiavelli, advocates of an autonomous role for the state, but that goal depended upon the ultimate subordination of the Church to the secular order. Others, like Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella, or the fictitious character Raphael Hythloday from Thomas More’s Utopia, dreamed of ideal models of society. These aspirations would, at their apotheosis, give birth to the murderous Marxist utopias of the 20th century. This strand of the intellectuals’ revolt against natural authority would be treated at length in one of Molnar’s later books, Utopia: The Perennial Heresy (1967), an indispensable guide to a tradition of heretical thought that is still very much with us, lurking even in the occult ambitions of Progressivism.

Allied not only to kings and princes, the intellectual class formed alliances with the rising bourgeois elites that increasingly occupied positions of power in the burgeoning cities of Europe as bankers, speculators, and founders of new institutions of learning—in short, the patrons and promoters of a new and glittering civil society. Thus, we find that by the time of the Enlightenment the major Western nations were swarming with men (and sometimes women) of the intelligentsia yearning to “emancipate” the long-suffering human race from the yoke of the priestly class, which they sought to replace.

If the Marquis de Condorcet might be said to have invented the “religion of progress” in his Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind (1795), his predecessor Jean-Jacques Rousseau was, Molnar noted, its “prophet.” Embarking upon a project of investigating “what is the nature of government which would form the most virtuous, enlightened, wise and best citizens …” (from Rousseau’s Confessions, 1756), he eventually proposed, in the Social Contract (1762), the momentous concept of the General Will, an attempt to restore to human society the lost unanimity that Rousseau traced back to the rise of civilization itself.

In the General Will, wrote Molnar, “Rousseau found a substitute for the Divine Will of Christian political philosophy. We are accustomed to suppose that the General Will is the forerunner of modern totalitarian thought, but Molnar insisted that its immediate importance for the 18th century, and particularly for the rising power of the bourgeoisie, lay in its guarantee that the “unified will of the nation” would become the fundamental law of the state. Magistrates would deploy their power not for king and aristocracy but “according to the intentions of the citizens.”

As this explosive quest for a utopian, universal polity unfolded over the two centuries that followed, it generated three fundamental ideologies, according to Molnar: Progressivism, Marxism (understood as the radical offshoot of socialism), and radical nationalism. By the end of World War II, it had become apparent (at least to most people in the West) that Marxism and radical nationalism were failed experiments resulting in the horrific loss of millions of lives.

As for the ideology of Progress, its failure has only gradually become more apparent. Drawing heavily on evolutionary theory, Progressivism has sought to bring about social consensus through propaganda or ideological pressure disguised as democratic persuasion. In reality, Molnar wrote, the progressive “favors the machine over man, [and] on the level of public policy he is inclined to entrust to huge, machinelike organizations the regulation of life,” a development manifest “in all parts of life where ‘progressive’ thinking has prevailed.”

Molnar was referring, of course, to the centralization of economies, the welfare state, and the “bureaucratization of human activity in general…” By now, vast sectors of citizens (or “clients”) of Western bureaucratic societies have, at some level, tried to reject such methods of control. Yet their revolts “against the machine” have, more often than not, been without political significance, except that they have become more and more difficult to govern without an ever-expanding system of penal control. This system is aided and abetted, of course, by Big Pharma, which expands its grip on the American psyche with each passing year. As of 2023, according to the American Psychological Association, nearly 40 million Americans were on psychotherapeutic medications to treat depression and anxiety.

The utopian project of the intellectuals has resulted in their decline in the sense that they no longer command widespread respect or trust. Moreover, Molnar observed that a new class has gradually risen to replace them: the social engineers, who would subject the “external man” to permanent and general reorganization. By contrast, the old class of intellectuals still believed in the “conquest of the inner man” (hence the illusion of persuasion, for example, on the part of the Progressives).

The intellectuals had sought a “sacralization” of the secular realm, drawing deeply from the well of the Christian mythos, Molnar wrote. The social engineers, by contrast, are not hampered by notions of transcendence or the illusion of personal choice. Rather, they are busy “furnishing their world with new objects and objectives. They have created, side by side with the world of nature, a parallel or second world, no longer situated in the same spatio-temporal and human continuum….”

Indeed, as Molnar argued in Twin Powers: Politics and the Sacred (1988), attempts by the old intellectual avant-garde to sacralize the secular have failed in part because such attempts are no longer seen as necessary. In our new postmodern order, the speculative, utopian quest for the ideal state, one that will guarantee true justice and social harmony, is simply misguided. Such a quest assumes that something like an “ethical consciousness” (in the Kantian sense) lies at the subjective core of our sovereign individuality. Yet our social scientists now tell us that “our conscious self is put together from a mosaic of contradictory impulses, sordid interests, secret desires, bundles of suppressed violence and other tumultuous drives.”

Why, then, our benevolent social engineers ask, should we trust in the existence of an ethical consciousness? What is needed, instead, is “a rational system of enlightened self-interest.” Suppose we object that such a philosophy reduces humanity to an undifferentiated herd, bereft of transcendence of any sort, secular or sacred. In that case, we are assured that belief in such a rational system will render it habitual until it becomes a “second reality.” Molnar wrote:

industrial-technological society … has constructed around us a world of conventions, rational and self-justifying without a transcendent reference. We have thus become more receptive to other purely rational systems, juridical, moral, and political.

In the most important chapter of Twin Powers, “The Restoration of the Sacred,” Molnar surveyed our present predicament. After successive waves of desacralization over the centuries, we have become increasingly aware of our spiritual poverty and the necessity of some form of the sacred—in our lives as individuals and our political arrangements. Serious thinkers are not thrilled by the one-dimensional “second reality” proposed by the social engineers, and they recognize well enough that the schemes of the utopians have been catastrophic. But most are not yet prepared to call for a return to the old sacred order, to recognize that power, when stripped of its sacred aura, cannot guarantee a unified social order, much less moral consensus.

Instead, they propose provisional forms of sacred, not reenactments of past foundational myths, but forms that arise out of our own creative powers. For example, the philosophical anthropologist Michael Landmann has exhorted us to shun the temptations of utopian thought—especially those forms of such thought embedded within our postmodern infatuation with technology—and to become makers of our own image. Each of us must become a creatura creatrix—a creating creature—while remaining open to the possibilities of the future.

French thinker Georges Burdeau argued for another possibility, claiming that an exit from our predicament can only begin with the desacralization of the very idea of power, which he said is “a curse.” Insofar as power is embodied in the state, he asserted, “we must at least emancipate [ourselves] from the humiliations that power inflicts by taming the mystery of the state.”

To this, Molnar objected that the taming of the state will not abolish the humiliations it inflicts. Power will simply retreat into “medieval forms” and cease to “advertise itself as power.” We cannot, he states, “produce a new sacred.” Those who think otherwise are offering not new forms of the sacred, but “collective therapies” rooted in “evolutionary hope” for a society without power (meaning without centers of repressive authority). Our hope lies not in evolution or in our own creative powers; those will not rescue us from what appears to be, on our present course, an inevitable slide into the “Hobbesian nightmare.” Our true hope, he concluded, lies in turning, in sackcloth and ashes, to the transcendent Christian God whom we have abandoned.

This return has already begun to occur in Molnar’s homeland, Hungary, where since his death in 2010 he has been celebrated as one of the chief inspirations in that country’s rejection of the malign influence of the European Union and its allies in the American foreign policy establishment.

Leave a Reply