The Kindhearted Conservative

Warren G. Harding came into office on March 4, 1921, thrust into the presidency at a time when the world was in the midst of an upheaval caused by the First World War. He entered the White House on the strength of the largest margin of victory in American presidential-election history, gaining more than 60 percent of the popular vote. He even carried the Southern state of Tennessee, a feat that had not been accomplished by a Republican in nearly half a century. It was not an electoral landslide, said one of Woodrow Wilson’s top aides: “It was an earthquake.” Yet, after serving fewer than 900 days in office, during which time he actually accomplished much, Harding’s presidency has been judged by those in academia to be one of the worst in American history.

Warren Harding was nothing like his predecessor, Woodrow Wilson, in either political philosophy or temperament. Wilson was a progressive and known to be haughty, arrogant, and self-righteous; Harding was the opposite, a consummate conservative governed by humility, kindness, and charity for all: principles that guided him in both his personal life and his political career.

Even as Harding rose from a young Ohio state senator all the way to the presidency, the political vice of ambition “did not stir him greatly,” wrote Henry Stoddard, of the New York Evening Mail. Back home in Marion, Harding was “the best known man in town,” but not because of his successful newspaper or the political offices he held. He was always known simply as “Warren,” and that’s the way he wanted it. One of his secret service agents described Harding as “the kindest man I ever knew.”

Such opinions of Harding are the rule, not the exception. Journalist Edward Lowry refers to a “kindliness and kindness that fairly radiate from [Harding]. He positively gives out even to the least sensitive a sense of brotherhood and innate goodwill toward his fellow man.” These traits are the “strongest Mr. Harding makes upon every one.”

Those serving with him in government had similar opinions. In the words of Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Harding was a “most kindly man.” Indiana Senator James Watson admired Harding for “his lovable nature” and said that he “was as intensely human in his sentiments and emotions and sympathies as any man I ever knew.”

Even those who did not particularly care for him, like New York Times reporter Charles Thompson, had to admit that Harding was “one of the kindest hearted of men. Never was there a man fuller of good feeling.” Harding spent hundreds of dollars every Christmas on gifts for the needy in Marion, Thompson noted, giving to the poor “more than any other man” in town. Harding’s “generosities were so numerous,” Thompson conceded, “and so constant that in Marion you never heard the same story from any two men; they always had their own stories, all different.” Harding exhibited “kindness to everybody” and possessed “a desire to do gracious little things to make life pleasanter.”

Just two days after winning the presidency in 1920, Harding penned a letter to the Literary Digest after reading an article about the need to help the 3.5 million children who were suffering as a result of the Great War in Europe. “Because such a movement for relief reveals the true heart of America,” he wrote, “because it bespeaks an American desire to play a great people’s part in relieving and restoring God’s own children, I want to commend and support your noble undertaking.” The American people should “share our good fortune in acts of sympathy and human fellowship. I wish you a success which will reveal anew the unselfishness of our great people.” President-elect Harding included a personal check for $2,500 ($37,000 in 2022 dollars).

These were contemporary opinions of the real Warren Harding, not the false caricature that has been portrayed in the century since his death. He was a man of great personal warmth and affection, perhaps more beloved by those around him than any other president.

When Harding won election to the White House on his 55th birthday, Nov. 2, 1920, America was in steep decline. In the words of one of President Wilson’s secret service agents, “This country is in a mess.”

Throughout 1919 and 1920, the nation had faced a number of serious problems: terrorism in the form of bombings by anarchist groups that targeted prominent Americans across the country; over 3,500 labor strikes involving more than 4 million workers; the “Red Summer” that saw violence against thousands of black Americans; and the onset of the “forgotten depression,” which lasted a year-and-a-half and saw the unemployment rate jump from 4 percent to around 12 percent while the gross national product fell 7 percent, causing many thousands of businesses to fail.

Americans, fed up with 20 years of progressive reforms, overseas wars, domestic strife, and an economy in rapid decline, turned to Harding. The people were certainly ready for a “return to normalcy.” Harding and his team, including Andrew Mellon as treasury secretary, quickly revived the American economy by cutting Wilson’s catastrophic taxes, which had grown to more than 70 percent at the top end, as well as his outrageous spending. These changes led to the most prosperous decade in U.S. history, an expansion that aided every class of citizen.

The federal budget the year before the United States entered the Great War was less than $800 million, and the national debt was about $1.2 billion. Yet the budget shot up to nearly $20 billion in 1919 and was still at more than $6 billion when Harding came into office, while the national debt had skyrocketed to $26 billion. Harding’s economic program would set the trajectory for the rest of the decade. With a 50-percent cut in appropriations and with spending tightly controlled, the government generated a budget surplus every year of the decade and paid off one-third of the national debt, which fell to $17 billion in 1929.

During the heart of the 1920s, specifically from 1922 to 1927, the economy averaged about 6-percent annual growth. Manufacturing output rose sharply, as did output per worker. By 1929, the U.S. GNP reached $103 billion (nearly $1 trillion in inflation-adjusted dollars), up from $70 billion in 1921, and the country was producing more than 40 percent of global manufactured goods. And just a few years prior, in 1926, the unemployment rate had reached its then-lowest point in U.S. history, at 1.6 percent.

This prosperity also helped push the nation forward, particularly with a boom in manufacturing, bringing technological advancement to the cities, where more Americans were now living. Electricity illuminated two-thirds of homes by 1929, twice as many as were lighted in 1920. Electricity also led to the mass production of new appliances: vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, washing machines, and radios filled many American homes by the end of the decade.

But what every American really wanted was an automobile, and with more money in their pocket because of the great prosperity, more people could afford one. The decade of the 1920s saw an increase in cars on the road from 10 million at the start to 26 million by 1929. More cars meant more roads were needed, so Harding had the foresight to sign the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 in order to help build new roadways across the country, which, in turn, led to such innovations as motels and roadside restaurants. Yet praise for these tremendous economic achievements is never given to Warren G. Harding.

Foreign policy is another major area where President Harding was very successful yet gets very little credit. Foreign affairs under Woodrow Wilson had been disastrous, as the nation turned away from its traditional noninterventionist policy. Harding sought to change that while also repairing the damage Wilson had caused. He called the Washington Naval Conference to reduce the world’s deadliest weapons, which also included a ban on the use of poison gas in the battlefield. He formally ended World War I, withdrew U.S. troops from parts of the Caribbean and from the Rhineland in Germany, called the World War Foreign Debt Commission to hammer out an agreement on war debt, and provided aid to millions of famine victims in Russia.

Unlike his internationalist predecessor, President Harding did not believe it was the mission of the United States to interfere with the internal affairs of other nations. Despite voting to declare war on Germany, he was not strongly on board with Wilson’s objective of making the world safe for democracy or, worse, imposing democracy on another nation.

As a senator, Harding once said that it was “none of our business what type of government any nation on this earth may choose to have.” In a private letter to former President Theodore Roosevelt, he wrote, “I have not thought it helpful to magnify the American purpose to force democracy upon the world. I do think it mightily essential that we establish the fact that democracy can well defend itself.”

Harding’s election to the presidency, as well as his ideals, pleased America’s closest neighbor greatly. The Mexican president, Álvaro Obregón, believed that the troubles plaguing the United States and Mexico were at an end. Obregón had described Woodrow Wilson as a “most terrible enemy” of Mexico but looked to Harding’s inauguration as “a day of deliverance.” Harding sent a message to be delivered to Obregón as an informal means of introduction during the transition period, citing his desire “for the most cordial and helpful and friendly relations between our two republics.” And in July 1921, Harding further expressed in a longer letter his belief that the friendship between the two countries “has not been fundamentally impaired” and that the key question left to be answered was “the manner in which we may re-establish and renew the outward form of its expression.”

The repaired relationship paid dividends. In August 1923, a few weeks after Harding’s death, diplomatic relations between the United States and Mexico were fully restored. For his accomplishments in foreign policy, Harding was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Harding also restored domestic tranquility, ushering in an era of peace to go along with the widespread prosperity. He pardoned war resisters, many of whom had been jailed under Wilson simply for disagreeing with the war. One of these was Eugene Debs, the nation’s leading socialist. Harding commuted his sentence in December 1921 with one condition: that Debs come to the White House to meet with him.

Harding was also the first 20th-century president to push for equal rights for black Americans, including a call for a federal anti-lynching bill. Traveling to Birmingham, Alabama, in the fall of 1921, Harding did something no other president up to that time had dared to do: deliver a speech in the heart of the Old Confederacy calling for equal treatment for blacks in the South.

Despite having less than three years in office, President Harding appointed four justices to the Supreme Court, including Chief Justice William Howard Taft, to safeguard the Constitution. Harding also began to transform the vice presidency by bringing his own vice president, Calvin Coolidge, more into the affairs of the executive branch.

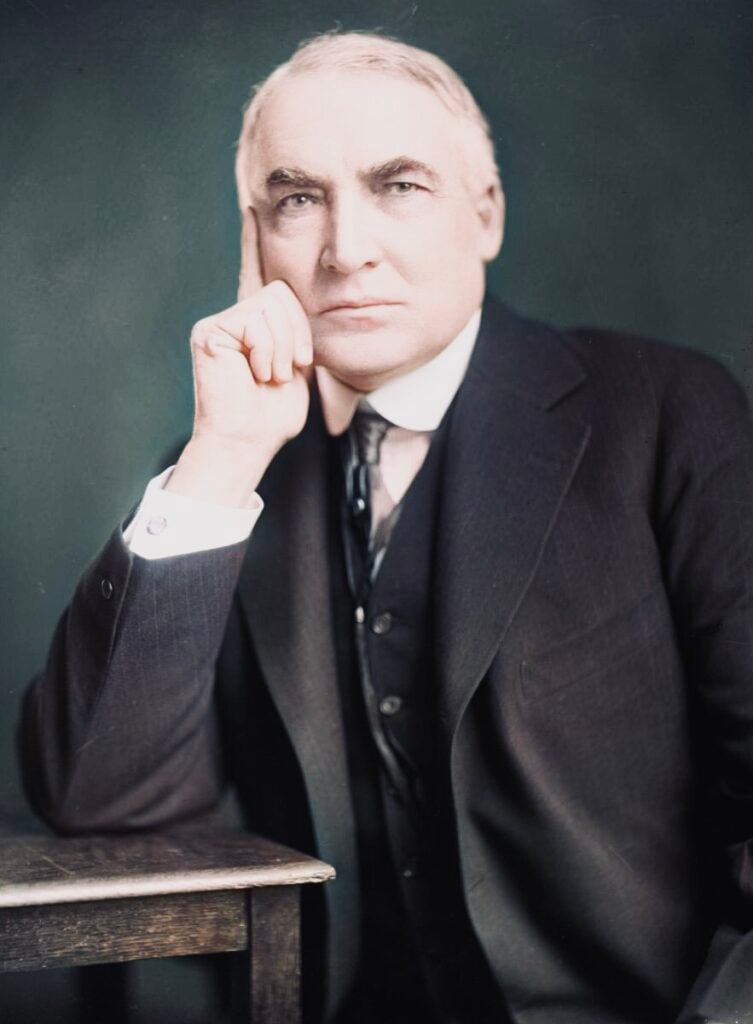

in front of a screen during a

photo shoot on June 17, 1920,

in his campaign for president

(National Photo Company

Collection / Library of Congress)

All of these accomplishments, as well as many others, Warren Harding managed to achieve in less time than John F. Kennedy was in office, yet Harding’s ranking is far below JFK’s. In fact, because of a century-long smear campaign, Harding has finished last in more presidential rankings than any other chief executive. But his record proves those rankings wrong. Harding is worthy of the highest respect and emulation, not denunciation.

No American president has been more vilified than Warren G. Harding. And no American president is more deserving of rehabilitation.

Leave a Reply