Two years after the death of the man whom one of his biographers, John Judis, dubbed the patron saint of modern conservatism, Encounter Books brought out a splendidly packaged omnibus volume of his columns and essays, entitled Athwart History: Half a Century of Polemics, Animadversions, and Illuminations (2010). On the cover, William Francis Buckley stands at the helm of a sailing vessel, an American flag flying high behind him, his hair tousled in a stiff wind, and a pair of sunglasses perched jauntily on his prominent nose. His smile can only be described as ebullient, not unlike the smile that we have seen in dozens of photographs of Buckley.

The photograph brilliantly captures the sheer magnetism of the man who stood at the helm of the National Review for 35 years—the magazine which he founded and which was the flagship publication of the American conservative movement. In the photograph, Buckley appears to be well into his 40s, so the vessel is very likely the Cyrano, a 40’ ketch upon which he made more than one transatlantic crossing. The name is suggestive. It alludes to Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac, a title taken eponymously from its hero, a multitalented nobleman and soldier who is celebrated for his charm, his wit, and his proboscis.

The choice says a lot about Buckley; it is at once a piece of braggadocio and yet a self-deprecating wink. This combination of qualities had long been a part of Buckley’s charm, dating at least from his college days at Yale, where he was legendary for his arrogance, but well-liked because he was always ready to laugh at himself.

Buckley’s personal charisma had a great deal to do with his ability to unify a majority of American conservatives of varying stripes around the principles of his movement. Moreover, he had been possessed since childhood of an iron will to succeed at everything he tried and he had the intelligence and good sense to do so at a very high level. Much of this drive was the legacy of his father and namesake, Will Buckley, a self-made man who made a fortune in the Mexican oil business in the first two decades of the 20th century, and whose influence over his 10 children was enormous.

Buckley pater, born in Texas, was of Irish-Catholic descent, deeply religious yet an extreme individualist in the American grain. Politically, he was an isolationist, a vocal opponent of the New Deal, a virulent anti-communist, and an advocate of laissez-faire capitalism. Yet he thought of himself not as a conservative but as a “counter-revolutionary.” The Buckley children largely adopted their father’s views, though none so ardently as his favorite son, Bill, whose legendary debating skills were first honed in the Buckley household and were brought to perfection at Yale. There his campus-wide acclaim was achieved in part because of his brilliant verbal acuity, but also because of his controversial pen, which he wielded as editor of the Yale Daily News. Even then, when one might have expected him to escape the shadow of his father, his politics remained in most respects identical.

This identification with his father was evident not only in his student productions but in his early books and articles. In McCarthy and His Enemies (1954), he and his co-author, L. Brent Bozell, adopted a position defending McCarthy that departed very little from what his father might have argued. However, Buckley, Jr. brought to the subject a sensitivity to McCarthy’s excesses and the vulgarity of the senator’s personal style that reflects a more polished sensibility.

For the most part, during the late ’40s and early ’50s, Buckley’s work remained sympathetic toward the Old Right, and vociferously libertarian regarding the intervention of the central state in the economy, as well as decentralist on states’ rights. Indeed, Albert J. Nock’s Our Enemy, the State (1935) had been a staple in the Buckley household, and young William remained an admirer, if not always a disciple, of Nock’s anti-statism all his life.

The founding of National Review in 1955 was, of course, Buckley’s central achievement. From the outset the magazine’s agenda signaled, at least implicitly, a break with the Old Right, at least on the issue of the Cold War communist threat. One indication of this break was Buckley’s association with Willi Schlamm, an ex-communist immigrant from Austria who, after fleeing the Nazis, worked for Henry Luce at Time, Inc., rising to the level of chief foreign policy advisor.

An admirer of McCarthy and His Enemies, Schlamm was eager to start a new magazine. Both men believed that an uncompromising anti-communism should be at the forefront of the brand of conservatism they hoped to promote. Domestic politics held no interest for Schlamm, and he was openly hostile toward the Old Right’s opposition to an expansionist foreign policy.

The Old Right, represented by figures such as Sen. Robert A. Taft, H. L. Mencken, and Albert Nock, as well as writers associated with the Southern Agrarians and a handful of right-leaning libertarians, had been the dominant conservative force in America since the 1920s. However, it was never a well-organized, nationwide movement with a unified agenda. While Buckley in his early years certainly aligned himself with the Old Right’s opposition to the New Deal, he had little interest in what he called their “isolationism,” or their regionalist concerns. According to Judis, “[Buckley] didn’t see himself defending the verities of small-town America, but rather arresting the assault of Soviet communism.”

What is indisputable is that Buckley was adept at surrounding himself with brilliant writers and editors. Many of them had the kind of intellectual pedigrees that would demand the attention of the Northeastern intelligentsia, who tended to associate conservatism with Chamber of Commerce business ethics and small-minded bigotry. In part to counter this perception, Buckley brought on board Catholics (like his brother-in-law and Yale debating partner, Bozell), Jews, and ex-communists. Among these were Will Herberg, Whittaker Chambers, and James Burnham.

Herberg, a Russian Jewish immigrant, had joined the Communist Party in 1920, then gravitated toward a “democratic socialist” position. By the early 1950s, he found himself increasingly aligned with conservative positions: anti-communism, anti-liberalism, and anti-secularism. Chambers, who became a senior editor for Buckley, was not only an ex-communist, but a part of the Soviet espionage “underground” in the 1930s. His bestselling book Witness (1952) was published in the aftermath of his widely publicized testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which identified a number of highly placed American officials as Soviet agents, including Alger Hiss at the State Department. Chambers’ skills as a writer and his unyielding courage against the domestic threat of communism made him a valuable asset in Buckley’s inner circle. Burnham, an ex-Trotskyite and OSS operative, would become, by Buckley’s own assessment at the time of Burnham’s retirement in 1978, the preeminent intellectual and ideological influence at National Review.

Herberg, a Russian Jewish immigrant, had joined the Communist Party in 1920, then gravitated toward a “democratic socialist” position. By the early 1950s, he found himself increasingly aligned with conservative positions: anti-communism, anti-liberalism, and anti-secularism. Chambers, who became a senior editor for Buckley, was not only an ex-communist, but a part of the Soviet espionage “underground” in the 1930s. His bestselling book Witness (1952) was published in the aftermath of his widely publicized testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee, which identified a number of highly placed American officials as Soviet agents, including Alger Hiss at the State Department. Chambers’ skills as a writer and his unyielding courage against the domestic threat of communism made him a valuable asset in Buckley’s inner circle. Burnham, an ex-Trotskyite and OSS operative, would become, by Buckley’s own assessment at the time of Burnham’s retirement in 1978, the preeminent intellectual and ideological influence at National Review.

If I have given special emphasis to the communist backgrounds of Buckley’s inner circle, it is because their almost single-minded devotion to the anti-communist cause during the Cold War drove them, and Buckley himself, to a position in tension with their avowed antipathy toward the growth of centralized government. Buckley had hoped from the beginning to build his new conservatism around a “fusionist” balancing, as enunciated by political philosopher Frank Meyer, of various strands of American conservative thought. These included the Old Right’s opposition to the expansion of the central state that had begun with the New Deal; the libertarian support for laissez-faire capitalism; and anti-communism.

Of course, all of those strands were in some sense anti-communist, but the Old Right and the libertarians, like Murray Rothbard, were adamantly opposed to an international crusade against the Soviets which would inevitably require an enormous enlargement of what Eisenhower would later call the “military-industrial complex.” Early on, Rothbard attacked National Review for its support of “overseas adventurism and empire building,” echoing the criticism of the Old Right novelist Louis Bromfield, who in 1954 accused anti-communist interventionists of seeking to extend the old “colonial system.”

There is no evidence that Buckley himself dreamed of a new imperialist system, even if it is true that the anti-communist ideology he promoted helped to justify the construction of an American empire, one founded upon the evangelical conviction that the Soviet menace was an unadulterated evil that had to be defeated at all costs.

In fact, Buckley’s willingness to abandon his commitment to the Old Right ideals of his father proved even more disturbing than Rothbard imagined. In a 1952 essay published in the magazine Commonweal, “The Party and the Deep Blue Sea,” Buckley was strikingly candid about the nature of the compromise he was prepared to make. He asserted that the critical issue was survival, a reality which many conservatives were unprepared to face. The “invincible aggressiveness” of the Soviet Union, he argued, would require a rearrangement of American “battle plans.” In short, “we have got to accept Big Government for the duration—for neither an offensive nor a defensive war can be waged…except through the instrument of a totalitarian bureaucracy within our shores.”

Buckley provided no indication of what the “duration” of this totalitarian response to a totalitarian threat might be. But he added that once the Cold War was won, conservatives would have to take up the task of securing a second victory against an “indigenous bureaucracy,” though the chances of winning such a victory would be “far greater than they could ever be against one controlled from abroad, one that would be nourished and protected by a world-wide Communist monolith.”

He repeated much the same argument late in 1954 in The Freeman, and his position throughout the Cold War tended toward a policy of aggressive “liberation” of Soviet satellite states rather than the more cautious policy of containment. In Buckley’s view, either strategy would require much the same bureaucratic expansion, “for to beat the Soviet Union we must, to an extent, imitate the Soviet Union.” That vague qualification (“to an extent”) begs a host of troubling questions.

While there was no shortage of Old Right criticism of this willingness to sup with the Devil, the most troubling warning came from across the Atlantic. George Orwell, in one of his last published articles before his death in 1950, restated an argument that had already been effectively spelled out in his novel 1984. The gravest danger posed by the rise of the modern super-states was that, whatever their outward ideological differences, they tended increasingly to resemble one another. Their bellicose propaganda was largely a manufactured attempt to consolidate power, while robbing their citizens of civil liberties.

Much of 1984, as Orwell never attempted to disguise, is based on the arguments of James Burnham’s The Managerial Revolution (1941). In this highly controversial work, and the book which followed, The Machiavellians (1943), Burnham revealed a theory of political power founded upon the idea of the inevitable rule of elites. While still a Trotskyite, Burnham, according to J.P. Diggins, had begun to view the modern state as neither solely a “reflection” of capitalist class interests nor as a “representation” of democratic majorities, but rather “an increasingly autonomous structural entity without exact precedent or analogy in the past.”

In the modern era. Burnham saw emerging a “new class” of bureaucratic experts, economic managers, scientists, commissars, and so on—a “managerial” class which was, in its essence, totalitarian. Orwell agreed with Burnham that managerialism was indeed the main trend of 20th-century politics, not only in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, but in New Deal America, as well. Yet he objected to Burnham’s technological determinism and was disturbed by his barely concealed admiration, especially in The Machiavellians, for the vigor and ruthless use of power by these new technocrats.

Orwell’s perspective raises pertinent questions. To what extent was Buckley swayed by Burnham’s power politics? Did he view the struggle against the Soviets within the same Machiavellian framework? That Burnham became, with Buckley’s blessing, the mouthpiece for foreign policy at the National Review suggests that to some extent their views were yoked.

In his Struggle for the World (1947), Burnham had argued for the establishment of an “American empire” intended to secure “decisive world control.” Under the flag of “democratic world order,” America would become a global hegemon, a “unifying power.” For more than two decades, Burnham pushed the same ideas in his National Review column, though not always so explicitly.

Aside from his earlier articles on the need for a temporary totalitarian regime to meet the Soviet threat, Buckley himself was usually more restrained than Burnham. Yet he was constantly at odds with the State Department and a succession of presidents over their lukewarm prosecution of the Cold War. There was too much appeasement and not enough aggression toward the Soviet menace, Buckley thought. Nor did Buckley, as far as I am aware, ever express serious concern over the growing power of what has been termed the National Security State, or even more colloquially, the Deep State.

Burnham and Buckley backed the war in Vietnam but complained when it was not prosecuted forcefully enough. Burnham went as far as to call for chemical weapons strikes against North Vietnam. Yet he also lamented during the same period, as in his 1959 book Congress and the American Tradition, the growth of Caesarism, or what today we might call the “imperial presidency.”

Not the first to notice the seeming contradiction, Burnham’s biographer Daniel Kelly asks, “How did he think the need to wage the Cold War…could be reconciled with the need to stem the growth of Caesarism, a phenomenon he attributed partly to twentieth-century wars, both hot and cold?” The same question could be asked about Buckley.

With the passage of time, National Review became firmly established as the voice of the conservative movement, though the movement remained largely outside the Beltway corridors of power. The defeat of Goldwater, whom Buckley had supported, was a blow, but the movement remained unified in the years leading up to the election of Ronald Reagan.

Unified, but not without a series of purges of those groups and individuals whom Buckley regarded as outside the pale. The John Birch Society was labeled anathema early on for the alleged anti-Semitism and conspiracy-ridden views of its leadership. Also proscribed were Ayn Rand and her ephebes, not because they were libertarians but because of their Nietzschean atheism.

Both of these purges were, in my view, justified. However, the early purging of “isolationist” libertarians must be considered lamentable. In addition, in the ’70s and ’80s fewer and fewer writers that were identifiably traditionalist or libertarian appeared in the magazine. As a number of observers have noted, Buckley drifted gradually into the neoconservative ambit, both politically and socially.

A few solidly paleoconservative writers remained on the editorial staff, including Chilton Williamson, Jr., who left in 1989 to join Chronicles. Also Joe Sobran served as a National Review senior editor for more than 20 years. Sobran was fired in 1992 after charges were leveled at him by Midge Decter and her husband Norman Podhoretz, editor at Commentary. The crux of the matter was that Sobran’s columns criticizing the “Israeli lobby” were deemed by Podhoretz and Decter—hypersensitive to perceived anti-Semetism as they were—to be scurrilous. In Decter’s words, Sobran himself was “little more than a crude and naked anti-Semite.”

Certainly Sobran had been quite critical of the Israelis, but anti-Semitic? Buckley thought not, and, to his credit, defended Sobran both publicly and privately, while at the same time writing in a private letter to Decter, “What Joe needs to know is that certain immunities properly attach to pro-Israeli sentiment for historical reasons.” In short, you are allowed to criticize Israel only if and when your pro-Israeli sentiments have been satisfactorily rubber-stamped by certain self-appointed gatekeepers. This had been, in fact, Podhoretz’s argument some years earlier in his much-debated polemic “J’Accuse” (1982) published in Commentary. But Sobran refused to accept such admonitions, hence his departure from National Review.

The culmination of Buckley’s success was to orchestrate the movement that led to the election of Reagan in 1980. The great irony is that in the process, he had to leave behind the “counter-revolutionary” that he had imagined himself to be in 1955, to become a pillar of the establishment. His relationship with Reagan thrived for some 30 years, and he was a major factor in the Great Communicator’s ascendancy. A gratified Reagan offered him a post as ambassador to Afghanistan (still at that time under Soviet occupation). Presumably, this was an instance of presidential humor, but is also an indication of the esteem in which he held Buckley, who remained an unofficial advisor throughout the Reagan era.

The culmination of Buckley’s success was to orchestrate the movement that led to the election of Reagan in 1980. The great irony is that in the process, he had to leave behind the “counter-revolutionary” that he had imagined himself to be in 1955, to become a pillar of the establishment. His relationship with Reagan thrived for some 30 years, and he was a major factor in the Great Communicator’s ascendancy. A gratified Reagan offered him a post as ambassador to Afghanistan (still at that time under Soviet occupation). Presumably, this was an instance of presidential humor, but is also an indication of the esteem in which he held Buckley, who remained an unofficial advisor throughout the Reagan era.

It is not my intention to besmirch Reagan’s ascendancy as a marker of Buckley’s accomplishment. America did move significantly toward conservatism in those years, and for the first time in decades liberalism was driven into a defensive mode.

There is no doubt that Buckley enjoyed being at the center of power, which is not in itself a crime. Yet, to place things in perspective, the Reagan years also marked the rising tide of the neoconservative occupation of Washington, and, as noted, it seems that Buckley had chosen to cast his anchor on the neocon side of the good ship conservatism. To be fair, he continued at times to criticize the liberal tendencies of the neoconservatives on social issues, on the welfare state, and more.

But perhaps the best indication of how far he had traveled from the traditionalist Old Right was his involvement in the move to block the appointment of Mel Bradford to head the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1981. The story is complex, but as Mark Gerson tells it in his The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (1996), prominent neoconservatives Irving Kristol and Edwin Feulner of the Heritage Foundation felt that Bradford’s earlier support of the presidential campaigns of George Wallace and, more importantly, his repeated attacks on Abraham Lincoln’s contribution to the “decline of the West,” would embarrass Reagan.

Kristol and Feulner pushed William Bennett—at that time a registered Democrat but a neocon ally—as an alternative candidate. Buckley, having had a long association with Bradford, was torn at first, but in the end he joined the neocons to convince Reagan to appoint Bennett. As Feulner wrote later, “It was a coalescing of the different parts of the movement…that showed that we could in fact work together, that we had common views.”

Further evidence of Buckley’s drift from the traditionalist right is evident in a collection of essays entitled American Conservative Thought in the Twentieth Century (1970), which he is credited with editing. While the essays selected for the volume are respectable enough, and do include a piece by Russell Kirk, Southern writers are conspicuous by their absence. It includes nothing by any of the Agrarians; nothing by Richard Weaver or Mel Bradford. What lay behind these omissions?

Perhaps it had something to do with the kind of Lockean individualism Buckley had always promoted, in contrast to the Southern advocacy of what Richard Weaver called “social bond” individualism, which places the individual firmly within the context of his ties to local and historical communities which, in the Southern view, were the only real bulwark against the power of the state. Perhaps it was this philosophical commitment to an essentialist, abstract individualism that led Buckley, in the end, to accept the notion that America is, in essence, a “proposition nation” in the Lincolnian sense.

Thus, just months before his death, Buckley wrote in a short piece for The Atlantic:

I would doubt any claim that the American idea is finally validated by historical and human experience. It is, for men and women of my perspective, judged to be secure in warranting perpetual loyalties. But ours are loyalties to an ideal, not to a revelation, and this must have been the reason, even if he was not conscious of it, why Lincoln referred to the American ‘proposition.’

It seems that Buckley’s counter-revolution ended, not with a bang but with an egalitarian whimper.

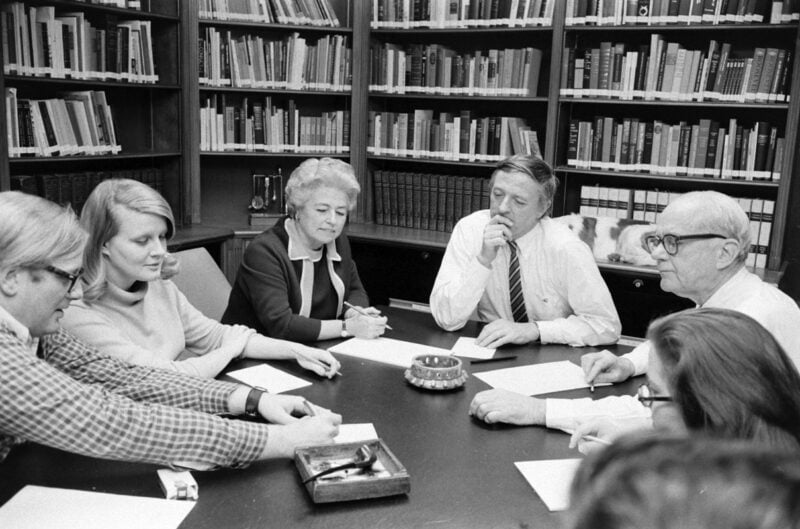

Image Credit: William F. Buckley, Jr., New York City, 1971

Leave a Reply