The reality of the Old West does not sit well with many in academe, who take pride in thinking they are debunking what they call cherished myths of the American people. I think this is especially the case when talking about gunfighters. There is clearly an impulse to attempt to destroy what most of us see as men of exceptional courage with nerves of steel. Better to deny such men existed—or you might be expected to live up to their example.

I was recently taped for a program focusing on the Hollywood version of the Old West. Not surprisingly, one of the questions that arose concerned the portrayal of the gunfighter. Did such a man ever really exist? Did he ever really face down an adversary in the street of a Western town and shoot it out? I got the feeling everyone expected me to answer that, other than Wild Bill Hickok and Dave Tutt letting lead fly in the town square of Springfield, Missouri, such a scenario occurred only on the silver screen. Somehow, this has become the prevailing wisdom, especially in academe.

James Butler Hickok and Davis K. Tutt both served in the Civil War, but on opposite sides—Hickok for the Union, and Tutt the Confederacy. July 1865 found them both in Springfield, Missouri, trying their luck as gamblers. Hickok occasionally lost more than he won. Tutt was a consistent winner, and one of those he often bested was Hickok. After one night of losing, Hickok used his prized Waltham gold pocket watch as collateral. Tutt scooped it off the card table, saying Hickok could have it back when he satisfied his debt. Grinning evilly at Hickok, Tutt called it a night and walked out of the card room. Hickok yelled after him, warning that he had better not see Tutt wearing that watch. Hickok understood that such an act would be an affront to his honor. Tutt understood that not wearing the watch would be cowardice.

The next morning Tutt was seen in Springfield’s public square with Hickok’s watch dangling conspicuously from the pocket of his coat. When Hickok got word of Tutt’s brazen display, he vowed to kill him. Friends intervened and tried to resolve the dispute over Hickok’s debt. They actually got the two men together later in the day. Tutt pulled out the watch and told Hickok he could have it back for $45. Hickok claimed the debt was only $25 and remarked that he’d rather “have a fuss with any man on earth” other than Dave Tutt, because he had borrowed money from Tutt time and again, and they had “never had any dispute before in our settlement.” Tutt said he didn’t want any difficulty, either. It was suggested that the debt be settled for $35. Neither Hickok nor Tutt would budge, both declaring it a matter of honor.

An hour later, Tutt was out on the public square again, walking along its north side, and again Hickok’s gold watch dangled from Tutt’s pocket. Within minutes, Hickok arrived on the square’s south side and called to Tutt. Turning toward Hickok, Tutt drew his revolver. At the same time, Hickok drew his. Witnesses claimed they only heard one shot: The adversaries fired at exactly the same moment. Hickok’s round struck Tutt on his right side and passed through his chest cavity. Tutt staggered for a few steps and then dropped to the ground, dead.

I’ve heard again and again scholars and others declaring that the Hickok-Tutt gunfight was a rare anomaly. Many have said that it was one of a kind, and that Hollywood seized upon it to create gunfights for movies that had no other real-life counterparts. Actually, there were dozens of gunfights in the Old West similar to the Hickok-Tutt scenario—hundreds, if gunfights inside saloons are included.

Two of Thomas Carberry’s gunfights fit the scenario perfectly. An Irish immigrant, Carberry became a notorious fighter in the mining camps of California and Nevada during the 1850’s and 60’s; 1867 found him in Austin, a silver-mining town located at the geographical center of Nevada. During the late 60’s, Austin was at the peak of its production and had a population of some 5,000. Carberry quickly established himself as the town’s most feared gunfighter.

Into the town in August 1867 came S.B. Vance, a gunman who had established his reputation in many of the same camps as had Carberry. Earlier in the 1860’s, in Aurora, Nevada, Vance and Carberry had even been members of the same gang. There may have been old animosities between the two, but what is known for certain is now, in Austin, Vance refused to accept a status inferior to Carberry’s and challenged him to a gunfight.

People, livestock, and wagons suddenly disappeared from Austin’s main street. Vance took a position in the street first. When Carberry appeared, Vance began shooting. Dissatisfied with the distance, Carberry held his fire and, with bullets whizzing by his head, began walking directly toward Vance. When Carberry judged he was at a proper range, he raised his gun in his right hand and rested it across his left arm, took careful aim, and shot Vance dead.

A year later, Carberry was in a second gunfight on Austin’s main street. Carberry and Charles Ridgely traded insults when an old grudge between the two erupted into an argument. Carberry told the unarmed Ridgely to get his pistol and meet him in the street. Minutes later, Ridgely stepped out of the International Hotel and into the street. Down the block, Carberry stepped off the elevated wooden sidewalk and into the street. Both men began firing simultaneously. Their first shots missed, as did Ridgely’s second and third. Ridgely didn’t have an opportunity to fire any more. Carberry’s second and third shots drilled Ridgely in the chest, and he died minutes later.

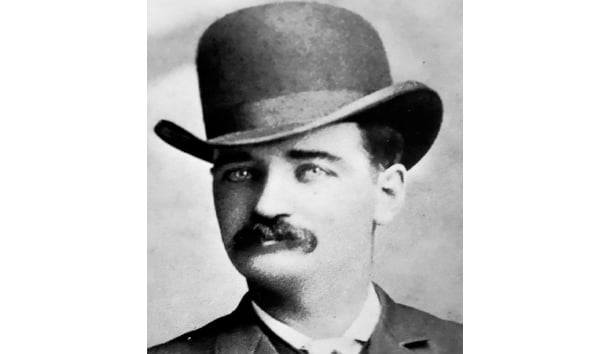

William B. “Bat” Masterson spent several decades of his life on the frontier, first as a buffalo hunter, Indian fighter, and Army scout, then as a saloonkeeper, county sheriff, deputy U.S. marshal, and gambler. He spent the last two decades of his life writing for the Morning Telegraph in New York City. No one knew the Old West in the post-Civil War era better than Masterson. Masterson said he had known “many courageous men in that vast territory lying west and south-west of the Missouri River—men who would when called upon face death with utter indifference as to consequences . . . ” He further noted,

Courage to step out and fight to the death with a pistol is but one of three qualities a man must possess in order to last very long in this hazardous business. A man may possess the greatest amount of courage possible and still be a pathetic failure as a “gun-fighter,” as men are often called in the West who have gained reputations as “man-killers.” Courage is of little use to a man who essays to arbitrate a difference with the pistol if he is inexperienced in the use of the weapon[.] . . . Then again he may possess both courage and experience and still fail if he lacks deliberation.

Any man who does not possess courage, proficiency in the use of fire-arms, and deliberation had better make up his mind . . . to settle his personal differences in some other manner than by appeal to the pistol. I have known men in the West whose courage could not be questioned and whose expertise with the pistol was simply marvelous, who fell easy victims before men who added deliberation to the other qualities.

Masterson identified the three essential qualities a gunfighter needed. First, a man had to be willing to put his life on the line. “I’ll die before I’ll run,” declared many a Westerner. Second, he had to have proficiency with firearms. Proficiency didn’t necessarily mean the quickest draw, which was usually not the critical factor in a gunfight. Accuracy was of far greater importance, and accuracy depended on regular practice with well-maintained guns. Third, the shooter had to go about the business of gunfighting deliberately, paying no heed to lead flying his way, focusing solely on his target, taking careful aim, and squeezing off a round.

Hickok was known not only to practice regularly with his Colt Navy revolvers—often shooting both right-handed and left-handed—but to clean, oil, and reload them daily. Occasionally, when target shooting, he was outshot by another marksman. An Army officer who bested Hickok during several target-shooting sessions finally could no longer conceal his glee and declared, “I’ve outshot you again, Wild Bill.”

Hickok replied, “That may be so, but those targets weren’t shooting back.”

If courage, proficiency, and deliberation were the qualities the most-feared gunfighters had in common, a particular physical type was not. They came in all shapes and sizes. One of the terrors of the California gold camps was Sam Brown. He stood at an even 6′ and was 200 lbs. of muscle, bone, and sinew in an era when the average man was 5’7″ and 140 lbs. With thick, red hair flowing to his shoulders, he was given the sobriquet Longhair Sam. He killed five men in gunfights in California before crossing the Sierras to Virginia City in Nevada and killing three more. One of the terrors of Texas and of the Kansas cattle towns was Ben Thompson. He was of average height and tended toward pudgy. Even as a young man, his hair was thinning and receding. Not counting his service in the Civil War as a Confederate soldier, he killed a half-dozen men in gunfights. Bat Masterson said of Thompson, “It is doubtful if in his time there was another man living who equalled him with a pistol in a life-and-death struggle.”

I’d like to think that we Americans still have in us some of the traits demonstrated again and again by the gunfighters of the Old West. As I watch hordes of Muslim immigrants from North Africa and the Near and Middle East romp through Europe, transforming large swaths of cities into something entirely alien to Western civilization, I wonder if it could happen here.

Not if thousands of Hickoks, Carberrys, Browns, and Thompsons are still among us.

Leave a Reply