My relationship with Barnes & Noble is fraught with emotion simply because it is a big bookstore, among other things. And I am one of those types—an inveterate reader—who is easily hooked. I was once embarrassed when a lady told me that she had caught herself reading soup-can labels: As one who had done the same, I managed to keep a straight face and not to volunteer any such truth about myself. Why confess precipitately when the truth might come in handy later on? In the meanwhile, I am rather like a drug addict just pretending to be looking for some aspirin.

Now that I have attained to a somehow youthful state of Old Age, I have discovered all sorts opportunities and challenges, and many of these are at Barnes & Noble, as they used to be at the disappeared Borders. There is the problem of the collapse of the recorded music industry, particularly as far as classical music is concerned, so that today even a mega bookstore has little to offer in the way of compact discs. And there are other such problems, one of which was instituted by Barnes & Noble itself: The magazines for sale are also offered for reading on the spot, with a comfortable bench as well. But why would the inquisitive reader buy a magazine when he can read it on the spot? And there are magazines that appeal to many levels of curiosity and fascination. There are magazines for women and for men, and even some for both. It’s not hard to imagine the degree to which magazines are aimed at the indulgence of fantasy. Rarely if ever have I seen a woman pick up a magazine about guns, or about exotic automobiles, or about golf, though they are perfectly welcome to do so. But however that may be, fictions are not the only fantasies that are indulged in print.

So before I address my topic of a thoughtful music magazine I found at Barnes & Noble, let me defer that specificity to insist on a more general point. An odd transformation has occurred in the publishing industry, which may be defined as the morphing of bookish topics into magazine subjects. If you are interested in the American Civil War or the Second World War, there are many books to supply your store of information and interpretation. Yes, but now there are also monthly magazines devoted to such historical topics. And there are many magazines devoted to many other surprising topics.

Now I was not surprised, the last time I was in Barnes & Noble, to see that they had several copies of the latest Chronicles—not surprised because a certain well-read lady, an editor and professor of English herself, had told me that Chronicles was the best-written magazine that she knew of. Otherwise, I could not reasonably expect to see magazines about classical music because these had been eliminated by Barnes & Noble itself—they didn’t stock Gramophone or BBC Music Magazine or other such magazines any more. But what they did present was Opera Now, with a striking cover photo of Ermonela Jaho. I have to admit that Ermonela was the sort of lady who clinched the deal—and that was without singing a note. I bought my copy altogether unread, as was justified upon examination—this American yahoo was convinced by the Albanian Jaho.

But when I did read the magazine, what I discovered was that Opera Now is not only a magazine about operatic productions, but also a promoter of, or at any rate a guide to, festivals on a global scale. When I say “global,” I mean just that. Inside the back cover, we find an announcement from the National Centre for the Performing Arts of Beijing. I believe I noticed three operas by contemporary Chinese composers, three by Verdi, two by Rossini, and so on. This festival—a matter of national policy—reminded me of the old saying that the only thing as expensive as opera is war. And it also reminded me that opera has been for four centuries a matter of cultural prestige and even political assertion.

Otherwise, much of the coverage of summer festivals is inclusive of presentations away from such established institutions as Bayreuth (where Hitler had an apartment and a detailed interest), Salzburg, and such like. There is a come-hither page from the Winter Opera of Sarasota, Florida, which is already in process, featuring the Turandot of Puccini, The Magic Flute of Mozart, the Nabucco of Verdi, and a comic double-bill of Donizetti’s Rita and Wolf-Ferrari’s Suzanna’s Secret. I have to think that a success in Sarasota is virtually assured by the presence of so many refugees from the northern winter.

But more challenging to our imagination perhaps is the Baltic emphasis iterated by Opera Now. The best-known festivals of music are glossed over so that we can be informed about the remarkable ones that are both historically rooted and also charged by contemporary developments, as Eastern Europe has emerged from the shadow of Russia.

In the order of their presentation, we find that the Estonian National Opera at Tallinn will soon be staging The Tsar’s Bride by Rimsky-Korsakov. The Latvian National Opera in Riga will be celebrating a century of opera. The Lithuanian City Opera is at Kaunas, not Vilnius; and we must note that opera has been in Lithuania for four centuries—pretty much since the beginning of opera itself. And there is now a second company, the Vilnius City Opera, so there is a particular vitality in the Lithuanian operatic situation.

While we contemplate this part of the world, the adjoining entities of Finland, Poland, and Russia are not to be scanted. Finland has its Savonlinna Festival in the summer, and new developments under the baton of Esa-Pekka Salonen and the presentation of established operas and new ones. Autumn Sonata by Sebastian Fagerlund (after Bergman’s film) was a successful new operatic composition. In Poland, Marek Weiss has been central to the production of revivals of well-regarded repertory. The tradition of opera and vocalism that is a part of Russian history is so well known that Vladimir Putin himself is a proponent of the Mariinsky Theatre. All who know great singers know the famous Russians, including in our own time Anna Netrebko and the prematurely deceased Dmitri Hvorostovsky.

But of course, not everything happens in the Baltics. In a British magazine and purview, Edward Loder’s 1855 Raymond and Agnes is cited, and rightly so. This Gothic melodrama had escaped my attention, and I am grateful to Opera Now for giving me the essential information—even if Raymond and Agnes was or is Opera Then.

Now having pointed to the global awareness of Opera Now and its emphasis in this issue on the Baltic operatic situation, I must add that, otherwise, the magazine has just about everything that you could ask for, and more. There are, for example, a “Pick of the Year” and “New Releases”; there is also a page devoted to the other magazines provided by Rhinegold Publishing, such as International Piano, Classical Music, Music Teacher, and Choir & Organ. Another sign of the magazine’s success is the severity of some criticism of flawed presentations in Opera Now. This free approach is itself a sign of a healthy magazine and an affirmation of the best standards.

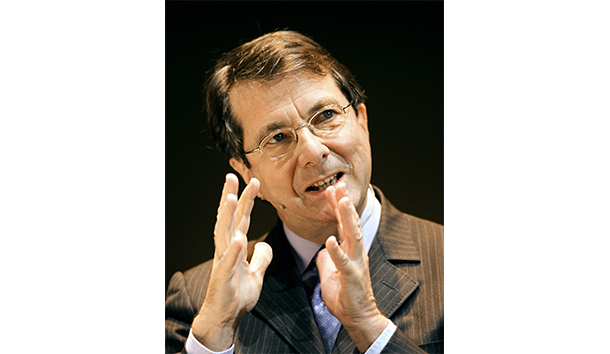

Another sign of standards is the doubt one writer ascribes to the reputation of the late Gerard Mortier, a man who received many honors in his life before his death in 2014. Mortier is a man who perhaps deserved to be treated much worse than with the restrained manner that was reasonably employed by Benjamin Ivry in Opera Now. Since Mortier was a man who was cut out to be anything but a director of opera—who essentially did not like opera itself—he deserved rather some kind of hatchet-job instead of the cool disposal that can be seen in Opera Now. Mortier was a pretentious leftist who used music for something that was unrelated to it—in short, propaganda. So even here, the magazine has shown its mannerly disposition—a quality that will serve it well in the long run of the future.

Leave a Reply