When the Vietnam War ended in 1975, over 58,000 Americans had lost their lives over the course of almost 20 years. Whatever one may think of the justice or prudence of the U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia, only the most callous of souls regards that loss of life with complete indifference.

When the Northern Illinois Women’s Center closed its doors for good in early January, after nearly 39 years of profiting from women’s exercise of their “constitutional right” to have an abortion, the death toll stood much higher than 58,000—perhaps as high as 70,000, according to Kevin Rilott of the Rockford Pro-Life Initiative. Before NIWC founder and first abortionist Richard Ragsdale passed to his eternal reward in 2004, he estimated that he alone had performed 50,000 abortions from April 1973.

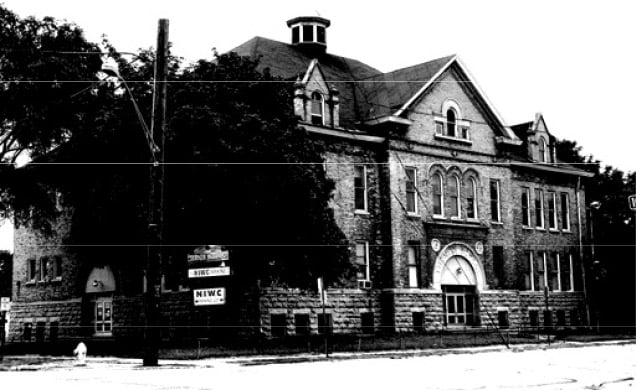

Yet how we regard that loss of life depends largely on what we think abortion is, and what we think abortion does. The many local Christians who prayed outside of the Northern Illinois Women’s Center every day that it was open over the course of four decades, and the many other Christians who supported them with prayers and donations, regard that loss of life with the same sadness as we do the death of American soldiers in Vietnam. And indeed, in that view, these children were the victims of a war, victims who had one distinct disadvantage over the soldier in Vietnam: They had no means or opportunity to fight back. Whatever chance they had to emerge unscathed from the house of horrors known as “Fort Turner”—a majestic old public school converted over to the destruction of life—came entirely through grace by the prayers of others.

For those who believe abortion does not stop a beating heart, but simply solves a problem or safeguards a “right,” there can be little question of mourning over the tens of thousands of lives lost. Even those who regarded the Vietnam War as just and necessary could view the loss of each American soldier’s life as a cause for grief, but in abortion, the child stands in for the enemy soldier, and even the best of us find it hard to mourn the loss of the enemy. That is simply the way the world works: In war, lives are cut short, futures erased, so that others may continue to live.

Of course, not all of those who support abortion have taken part in the killing. While the armchair warriors in the media and think tanks are more bloodthirsty than the average soldier, because they do not have to spend the rest of their lives remembering the faces of those their rhetoric has killed, the mothers who end the life of the children growing within their wombs are, like the soldier, much more likely than the abstract defender of “our way of life” to recognize what they have done, even if guilt compels them to continue to justify it as necessary. The woman who proudly proclaims that she has had several abortions and would gladly have another reminds the normal person of the veteran who laments that he had but one tour of duty to kill for his country.

On Monday, January 23, ten days after the Northern Illinois Women’s Center announced that it would close its doors for good, and 39 years and one day after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Roe v. Wade, our eighth child was born. Because the anniversary of Roe fell on a Sunday this year, the organizers of the annual March for Life in Washington, D.C., decided to transfer it to that Monday, as if it were, say, Martin Luther King, Jr., Day. Interestingly, the supporters of Roe followed suit—a curious sign, on both sides, of how much of the battle over abortion has entered the realm of abstraction.

When, however, your child is born on the day that all of America is either celebrating or commemorating the right of mothers to kill their own children, abstraction is simply not possible. To receive hearty congratulations on the birth of your child on, say, Facebook, offered by those who have spent the rest of the day expressing their gratitude for Roe and attacking those who acknowledge that life begins at conception, is profoundly chilling.

When did Clare Frances’s life begin? Not when she emerged via C-section from her mother’s womb a week before her due date—a time when many states would still allow a “late-term” abortion to “save the life of the mother.” Nor did it begin 15 weeks earlier, when she reached the point of viability—before which almost every state would have allowed her life to be ended to “preserve the health of the mother.” Nor did it begin another eight or so weeks before, when Amy first could be certain that she felt Clare move. Nor six weeks before that, when, at ten weeks’ gestation, we first heard her heartbeat, and when abortion is legal in every state for any reason. Indeed, her heart had been beating since the 23rd day after her conception, a time when many a first-time mother is only just beginning to sense that her life is about to change forever.

Physically, Clare Frances’s life began at conception; but even that does not tell the whole story. “Before I formed you in the womb, I knew you“ (Jeremiah 1:5), and before she was conceived, Clare existed in the sacramental union between Amy and myself. That, however, is a thought to develop in a different piece on another day. For now, suffice it to say that if we reduce the beginning of life to a biological milestone, we will never understand just how destructive abortion truly is.

I first visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Wall, a few years after it opened, and found myself there frequently when I was a graduate student at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. The impact of the Wall on visitors is often ascribed to the fact that the war remains close to us in time. But I think there is something more to it. Seeing those 58,261 names all brought together in such a small space distills the very real human costs of the Vietnam War. The visitor standing in front of the Wall cannot escape the consequences of our actions in Southeast Asia. And the very design of the wall gives the impression that this is just the tip of the iceberg, that behind and beneath each name lie mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters and children and friends, all the lives that the fallen had touched, and those that they would have touched, had they survived the war.

Fort Turner is, in its own way, just the tip of the iceberg represented by the tens of thousands of children whose lives ended therein. Might it, one day, become a monument to the war on the unborn, to the tens of millions of lives lost through legalized abortion, and to the hundreds of millions of lives affected by that loss?

Perhaps, but it will not be any day soon. Just as the Wall could not be built until the war had ended and the nation had begun to come to grips with the destruction it had caused, so, too, we will never fully comprehend the horror of legalized abortion until we have moved beyond it. Fort Turner, pray God, may remain shuttered for good, but its heart of darkness long ago outgrew its walls and is spreading throughout the land.

Leave a Reply