Few jazz pianists are “accompanists” as gifted in knowledge, technique, and taste as Norman Simmons, able to back vocalists with consummate skill in chording, passing notes, and background lines, but also wise in the use of space. “A pianist is a piano player—that’s different from accompanying,” Simmons said recently, as he approached his 85th birthday. “The idea of dealing with space means you have to learn what not to play. You hear this in Ellington, the way he wrote for his band, how he allowed his soloists that space. When I was with Carmen McRae all through the 1960’s, and she was already an accomplished pianist herself, she told me that the pianists who play for themselves, they didn’t play while they were singing. The singers I was with wanted to be independent. They controlled their own space, so we both had a sense of independence.”

Simmons has long been known to his peers and to jazz insiders as something of a renaissance man of the piano, a philosopher. And “multitalented” hardly begins to describe him: swinging soloist, arranger, composer, recording artist, coach, educator, author, for some 30 years owner of his own record label, Milljac Records—and veteran accompanist to many of jazz’s standout vocalists. A short list might include Helen Humes, Ernestine Anderson, Anita O’Day, Dakota Staton, Mavis Rivers, Betty Carter, Carol Sloane, Teri Thornton, Carmen McRae (whom Simmons backed almost continually from 1961 to 1969), and later Joe Williams, the only male singer he ever backed regularly.

A native of Chicago, Simmons moved to New York in 1959, bringing with him the experience and lessons learned during some three years as house pianist at The Bee Hive, one of the Second City’s top South Side jazz clubs until it closed in 1956, and where he backed visiting modern-jazz soloists like Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, J.J. Johnson, and Kai Winding and singers like Al Hibbler, Big Joe Turner, and T-Bone Walker. He also led his own nine-piece band at the C&C Lounge farther down on the South Side. “In a way I was lucky, Chicago was a very earthy place, and it was like everybody sang, all over town. You could always find work in Chicago. It was a strong rhythm-and-blues town, heavily blues because of that type of music, and you got that instinctive blues foundation, so it was a different kind of place from Detroit, which was more Eastern in a way. But all the Chicago pianists in those days could solo and accompany. Later, I had to work to develop my bebop playing, but early on I had to learn to work in a support role because of the way Chicago was.”

Dealing with such a variety of personalities might be unnerving for someone less adaptable or even-tempered, or for a pianist wanting to focus on his own solos. “Some guys, especially when they came east to New York, wanted to be in the foreground, today almost everyone does, and you can’t blame them. But working with a singer, the relationship is important—most singers want to develop a relationship, they’d like someone good who wanted to stay with them for a while. Now if they decide to let someone go, that’s different.”

Simmons remembers Carmen McRae fondly. “Carmen was unusual, she taught me things that she’d learned from being a pianist herself. She really taught me what an accompanist was in general. And she still played piano, in nightclubs she’d almost always sit down and play a couple of songs during the evening. But she was a songstress, and Sarah Vaughan was a songstress, so they were different from Anita O’Day and Betty Carter, who used songs more instrumentally. They were more interested in the musical elements, the notes, than [in] the lyrics. Anita nearly never sang a ballad, everything was uptempo, and she liked me to be feeding her lines, not just comping. Ernestine Anderson was very soulful, very playful, you could hear the ironic playfulness even in blues, for example. With Dakota, her delivery was more like a complaint. Helen Humes didn’t take herself too seriously, she was nice to everybody, and it showed in her singing. Carmen was also different because most vocalists travel with a limited repertoire. Some vocalists will go out with only 20 or 30 songs. But Carmen must have had 500 tunes, and every night was a personal selection for her; she’d pick the tunes herself, depending on how she felt that evening. She didn’t repeat tunes very often.”

Simmons is concerned about today’s lack of decent material. “In the 1960’s, we were getting a lot of music coming out of Broadway. Today, there’s pretty much no new music coming from Broadway that’s useful for jazz vocalists. Back in those days, with all those terrific composers, the guys played the songs that the composers wrote. It was the songs that made the singers, not the other way around. The listener could follow the harmonic structure from the beginning of the tune right on through, great melodies. But the compositional element has gotten weak today, some of these folks aren’t exactly trained composers, they’re writing licks, not music. New singers don’t have any new music that they can take as their own.”

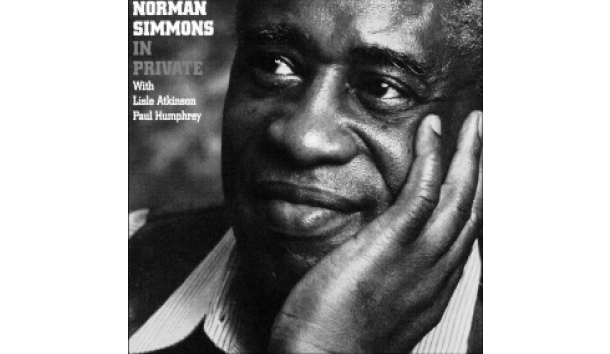

Simmons, like most musicians, is willing to pick his favorites from the dozens of recordings in which he has taken part for the Columbia, Argo, Riverside, Roulette, Prestige, Pablo, and other record labels. He is content with a number of his own albums such as In Private, a 2004 trio session with bassist Lisle Atkinson and drummer Paul Humphrey on which the group works over first-rate standards “Stella By Starlight” and “It Could Happen to You,” a Brazilian medley, a Simmons original, even a Chopin waltz; and I’m . . . the Blues, a 1981 quintet featuring trumpeter Jimmy Owens and tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan on several blues numbers and a wonderful version of “Why Try to Change Me Now.” He likes The Big Soul-Band, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin’s 1960 little-big-band date that featured such top guest players as pianist Harold Mabern, trumpeter Clark Terry, and trombonist Julian Priester playing Simmons’ arrangements and three of the pianist’s originals. Of his many recordings with vocalists, he is especially partial to the 1961 studio LP Carmen McRae Sings “Lover Man” and Other Billie Holiday Classics. Holiday, who had died only two years earlier, was McRae’s greatest influence and inspiration, and the date showcases the guest solos of Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis on tenor saxophone, Nat Adderley on cornet, and Mundell Lowe on guitar, Simmons’ sensitive comping anchoring a superb rhythm section with bassist Bob Cranshaw and drummer Walter Perkins, backing McRae on “Strange Fruit,” “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” “God Bless the Child,” “Some Other Spring,” “Trav’lin’ Light,” and several others. It was McRae’s first LP for Columbia Records after five years with the Decca label and its affiliate, Kapp Records, and the selections were McRae’s. “Now this was a dynamite album, and they were her choices,” recalls Simmons, “which was interesting, because usually the record companies would tell you what they wanted you to do, what songs they wanted.”

Joe Williams, the powerful blues-and-ballad-oriented vocalist featured with Count Basie’s Orchestra from 1954 to 1961 and with whom Simmons worked for nearly 20 years throughout the 1980’s and until Williams died in early 1999, remains to this day the sole male vocalist he worked and traveled with on an extended basis. “The relationship was closer because it was guy-to-guy, more basic; women’s demands and dependencies are different. And back in those days it was very much a man’s world, anyway, and we got along great. Joe was exemplary, he was truly a vocal jazz musician, and very flexible. We could always react to each other. Remember, he’d hung out with the Basie band at rehearsals and was very observant, very musical; he knew his music as well as any instrumentalist.”

It’s clear that many facets of the music business have changed in recent years, and not always for the better. Most of the clubs Simmons played in the earlier years are gone along with many of his old colleagues, and young jazz players’ attitudes are different. “In those days there was more of musicians being interested in singers and singers interested in what the musicians around them were doing. Today, most of the younger players have never worked under a senior leader like Art Blakey, who might teach them real things. They’ve come out of school, and their music is just about mastering the instrument, but they have no story in their playing, and their teachers aren’t teaching it to them. Our culture is so technology-based, and today a lot of the recording business has been turned over to the tech side; they figure you can fix things later on. But there are some things that never change. An accompanist’s job, an accompanist’s function, is to make the singer feel comfortable. That never changes.”

Leave a Reply