“There is no such thing as a moral

or an immoral book. Books are well

written, or badly written. That is all.”—Oscar Wilde, from the Preface to

The Picture of Dorian Gray

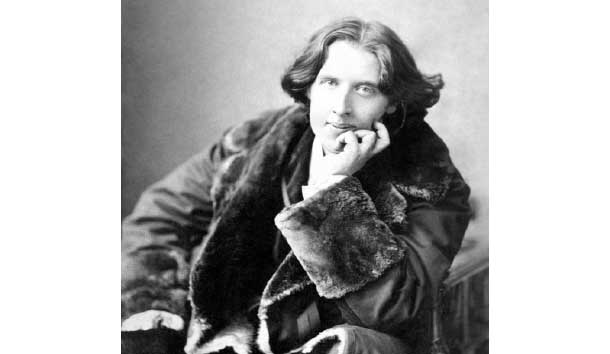

Oscar Wilde wrote several first-rate plays, on which his literary reputation principally rests, and a number of mostly second-rate poems. He is also lauded, quite rightly, for his short stories, mainly for children, of which “The Selfish Giant” and “The Canterville Ghost” warrant special mention. He wrote only one novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which is one of the finest written during a literary golden era that Chesterton celebrated in his Victorian Age in Literature. However, Wilde is not remembered by most people for his literary oeuvre but for the scandal surrounding his private life. Having deserted his wife and two young sons in pursuit of sodomy, he was sent to prison in 1895. Demonized by his contemporaries for the moral iconoclasm of his sexual choices, he is now lionized by many as a “martyr” for the cause of (homo)sexual “liberation.” The risibly inappropriate nature of the latter judgment is made manifest by Wilde’s description of his own homosexuality as a “pathology,” a statement that could land him in jail in some European countries in our own “liberated” age for the heinous crime of homophobia.

Wilde would not have been happy with the manner in which his literary achievement has been partially eclipsed by the sordid and squalid details of his private life. “You knew what my Art was to me,” he wrote to Lord Alfred Douglas, his “friend” and nemesis, “the great primal note by which I had revealed, first myself to myself, and then myself to the world; the real passion of my life; the love to which all other loves were as marsh-water to red wine.” Wilde died in disgraced exile, in Paris, in garret poverty, fearing that future generations would see only the marsh water of his murky “loves” while leaving the wine of his art untasted. In his final hours he was received into the Catholic Church, being fortified and consoled by the Last Rites. It was the consummation of a lifelong and flirtatious love affair with Christ and His Church that stretched back to his days as an undergraduate in Dublin.

What are we to make of this most beguiled and beguiling, this most confused and confusing of men? Does he have anything of value to teach us? Is his work relevant to our own times? Is his art an icon, revealing the image of Christ and His Truth to the world, or is it iconoclastic, seeking to tear down Christian civilization in a frenzy of debauched decadence?

As we attempt to solve this riddle, we are confronted by the provocative Preface with which Wilde raises the curtain on his novel. It says something of the power of Wilde’s aphoristic wit, which was the toast of the salons of London and Paris before his downfall, that these two pages are almost as well known as the novel itself and almost outshine it in brilliance. Take, for example, Wilde’s vituperatively splenetic judgment on his own age:

The nineteenth century dislike of realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.

The nineteenth century dislike of romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

For Wilde, late Victorian England is synonymous with the monstrous subhuman character in Shakespeare’s The Tempest who is bereft of all culture, all civilized values, and all Christian virtues, whose physical deformity is a reflection of his moral and spiritual ugliness, and whose very name, effectively an anagram of cannibal, cries out against him. Such an age hates realism because it cannot bear to see the ugly truth about itself, but it also hates romanticism because it refuses to see the existence of a beauty beyond its own ugliness. An age that can’t bear to look at itself and can’t bear to look beyond itself is in trouble!

Having held up a Swiftian mirror of satirical scorn to his own age, Wilde praises those who are open to the gifts of beauty:

Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault.

Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope.

This emphatic emphasis on the objective presence of beauty, which is not in the eye of the beholder, serves as a condemnation of the blindness of cynicism which cannot see beauty even when it is shown it, perceiving only ugliness. This calls to mind a line from one of Wilde’s plays in which a cynic is defined as one who sees the price of everything and the value of nothing. The cynic is a relativist who cannot see that which is intrinsically beautiful, a thing’s inherent value, but only that which is subject to the fluctuations of his own fleeting feelings, the price he assigns to it at any given time, which is always subject to change.

Thus far, Wilde appears as a tradition-oriented aesthete, reflecting his long-standing preference for the aesthetic of John Ruskin over that of the modernist Walter Pater, though both men had deeply influenced Wilde during his formative years at Oxford. Yet this traditionalist aesthetic is largely ignored by modern critics who prefer to accentuate Wilde’s claim in the same Preface that art is beyond morality: “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

This elevation of beauty over morality does violence to the traditional transcendental triad of the good, the true, and the beautiful, which Christian philosophers have rightly connected to the Trinity. To separate the beautiful from the good (virtue) and the true (reason) is to do violence to the cosmos itself. This is the ontological equivalent of splitting the atom, as explosive and as destructive metaphysically as the atom bomb is physically. It is no wonder that Wilde’s iconoclastic bomb, dropped with seeming nonchalance into the midst of his Preface, is quoted ad nauseam by those seeking the nihilistic deconstruction and destruction of meaning.

There is, however, a delicious paradox in the fact that Wilde flagrantly denies and defies his own aphorism in the writing of the novel, whose narrative is a vision of morality that is profoundly Christian and seems to prophesy his own eventual conversion. Dorian Gray, inspired by his own vanity and by the iconoclastic philosophy of his satanic tempter (Lord Henry Wotton), sells his soul to the devil in exchange for the retention of his boyish good looks. As Gray indulges his sensual appetites with an increasingly insatiable hunger, his portrait grows uglier and more cruel, a mirror of the corruption of his soul.

In the midst of Gray’s descent into ever-deepening pits of depravity, he is given a “yellow book” by Lord Henry Wotton, which, from the description that Wilde gives of its lurid plot, is quite obviously Huysmans’ decadent masterpiece À Rebours, a novel that depicts the protagonist’s life of sheer sensual self-indulgence as leading to an ultimate scream of despair and a desperate desire for God. Wilde’s protagonist follows the same downward path, except that Dorian Gray refuses to repent. Instead, he begins to despise the portrait, which is now hideously grotesque and spattered with the blood that he has spilled. Seeing the painting as a reflection of his conscience—and a reflection of his soul—he decides to destroy it so that he might enjoy his sins without the painting’s hideous reminder of their consequences. His effort to destroy it proves fatal—indeed, suicidal. The moral, as inescapable as it is clear, is that the killing of the conscience is the killing of the soul, and that the killing of the soul is the killing of the self.

In his own appraisal of the novel, Wilde contradicted his own aphorism by stating that “there is a terrible moral in Dorian Gray—a moral which the prurient will not be able to find in it, but which will be revealed to all whose minds are healthy.” Like all good art, of which Dorian Gray’s portrait is itself a powerful symbol, Wilde’s novel holds up a mirror to its reader. It shows us ourselves and teaches us the terrible lessons that we need to learn.

There are indeed such things as moral and immoral books, whether well written or badly written. Moral books show us ourselves and our place in the cosmos. They are epiphanies of grace. Immoral books are like Lord Henry Wotton in Wilde’s story or, indeed, like the Devil himself in the story in which we are all living. They are liars and deceivers who show us a false picture of ourselves and the world in which we live. Moral books wake us up; immoral books lull us to sleep. The Picture of Dorian Gray stirs us from the somnambulant path of least resistance that leads to Hell. For this reason, if for no other, we should thank Heaven for the vision of Hell that Wilde’s novel reveals to us.

Leave a Reply