Havilah Babcock was a teacher who was once one of the best-known educators in South Carolina and a writer who had a national audience. Today, few remember him. This is partly because of the passage of time—Babcock died in 1964. It is more owing to changes in American life and literature.

Babcock was a proud Southerner who taught and wrote about the best of Southern life, and that always meant hunting, fishing, and other outdoor pursuits. He was a true Southern agrarian. Yet, unlike those from the more famous literary circle, his agrarianism was more practical than philosophical and critical. Rather than a professor who happened to write about the outdoors, Babcock was an outdoorsman who happened to be a professor.

I did not hear of Havilah Babcock until about 15 years ago, when an old college friend contacted me after learning I taught at the University of South Carolina, Babcock’s former academic home. I started to read Babcock, beginning with his 1958 classic I Don’t Want to Shoot an Elephant, in which he defended the local hunter, his love of place and desire for a modest trophy—like a quail—against those who gallivanted around the globe to shoot something exotic and massive. In reading this and his other works, I gained insight into a unique man and his vision of the good life.

Havilah Babcock was born in Appomattox County, Virginia, in 1898. He was raised on a farm there and later matriculated at the University of Virginia. He came to teach at the University of South Carolina in 1926 after a year’s leave from teaching at William and Mary. Babcock found the hunting and fishing so good, and the people so hospitable, that he decided to stay. He finished his Ph.D. in English, later became department head (he served for 26 years), and made it one of the best programs in the university. He was devoted to the study of the English language, to his students, and to the state of South Carolina. His courses became so popular that students would sign up a year in advance to secure a place.

Babcock was a seminal figure in the growth of the university, especially in his advocacy of continuing education, which he felt was an integral part of the university’s mission. His commitment to public service and the sporting life also made him an early supporter of conservation. He was president of both the South Carolina Fish and Game Association and the South Carolina Wildlife Federation, and was National Director of the Izaak Walton League.

But Babcock was always best known as a writer. He honed a unique style—a blend of humor, wisdom, and stirring tales of outdoor adventures. His engaging prose caused him to be read widely, and he was a regular contributor to Field & Stream, Sports Afield, and other outdoor magazines. He published several books of his collected stories, all of which are now hunting and fishing classics. Despite his simple folksy style, Babcock spent long hours in solitude honing his craft, an avocation he had pursued since he was a young boy.

Besides telling wonderful outdoor tales, Babcock appreciated the Southern landscape and was one of the first to make it known to the entire country. He saw the South’s much-maligned swamps as beautiful places, noting,

A serpentine black-water creek that steals its way through a brooding cypress swamp is to me a thing of dark enchantment, a mystic and primeval region where the strangest things happen naturally.

Today, swamps (or wetlands, as scientists and bureaucrats call them) are severely threatened, though they are now known to be critical to sustaining healthy plant, animal, and human communities.

Most of Babcock’s writings focused on the South Carolina Low Country, a place he described as “tempered by a leisureliness and gentility savoring of an ancient, half-forgotten regime.” He helped bring a new perspective on the region, once the center of the South Carolina slave economy, showing it to be a distinct natural and cultural realm, one to be celebrated and enjoyed. And it was a sportsman’s paradise. Its rivers and swamps were excellent fishing spots, especially for bream, which Babcock placed above all other fish.

Babcock waxed poetic about the copperhead bream (bluegill) and especially the redbreast bream:

It is perhaps the most brilliantly hued of all fresh-water game fish. It is also distinguished by the great verve and spirit with which it attacks . . . And Southerners may not agree in politics, but they are “plumb unanimous” in the opinion that the red-breasted bream are the most savory pan fish with which benevolent Providence ever blessed a favored commonwealth.

The Low Country was an equally good hunting ground. Babcock once remarked that,

Of all the things I have enjoyed on this terraqueous globe—that I am willing to set down on paper—the one I have enjoyed the most has been bird hunting in the fabled Low Country of South Carolina.

Every fall Babcock would set off to hunt for days at a time. He once got into trouble after he instructed his secretary to put a note on the classroom door at the beginning of hunting season that stated, “Professor Babcock will be sick all next week.” Fittingly, the title of Babcock’s first collection of essays was My Health Is Better in November (1947).

Babcock’s favorite quarry was the bobwhite quail, and he believed he probably spent more time writing about and pursuing Colinus virginianus in the Deep South than any other living person.

I had rather hunt quail than do anything else in the world. Well, almost anything anyway. It is then that my spirits are buoyant, my disposition amiable, and my language chaste. And my gastric juices flow along with a sweet unawareness.

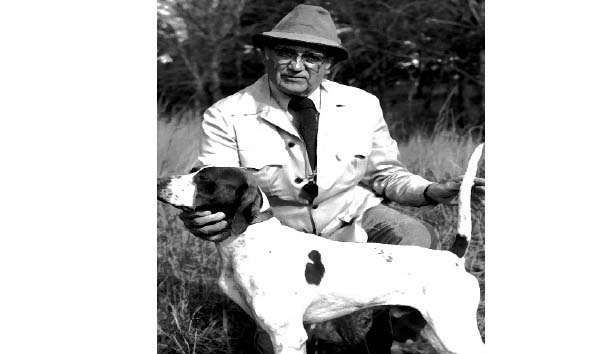

Naturally, he was devoted to his bird dogs and wrote many a tale about those he had known and raised in his years of hunting. He believed a good dog was like a virtuous woman: Both had a price far above rubies.

He was as devoted to his wife, Alice—also from Appomattox County—as to his dogs. She put up with his hunting and fishing habits and his hunting and fishing friends. Babcock defended his role as a husband, stating that “(1) Men who hunt and fish make better husbands than those who don’t and (2) A man who is not hunting and fishing is probably doing something worse.”

Babcock was a keen student of people and he always described South Carolina’s rural folk—both black and white—with insight and compassion. Like most white Southerners of his generation Babcock did use terms to describe black people that are now deemed offensive. But he was never insulting, condescending, or malicious. He genuinely appreciated the innate hunting and fishing skills of rural black people, who were his constant guides and companions. And he always preferred the company of all rural folk to that of academics, writers, and critics.

As a student of language, he was particularly fond of the rich Southern vernacular—both black and white—and how Southerners always invented new words or distinct variations on them. For example, most Southerners called a bobwhite quail a partridge, bass were commonly referred to as trout, a pickerel was a jack, a crappie a goggle-eye, and the lowly bowfin was demoted even further to mudfish.

Babcock appreciated good conversation (now a dying art in the age of “communications”), calling it the “great beguiler of time and abridger of distance.” To him, conversation was one of the great expressions of human freedom because it operated without rules or regulations and rambled from topic to topic. Babcock remarked that, once rules are applied to conversation, it becomes a conference, which is “a swapping of ignorance and an exercise in mutual boredom.” Good conversation also made it possible to endure inclement weather or long hours as one waited for that fish to bite or bird to show. Of course, good conversation required good companions, which was almost always one’s hunting and fishing partners.

What made Havilah Babcock’s writing so appealing is that he did more than spin a good yarn. He was a nature philosopher in his own right. He firmly believed that people need nature because people are children of the earth, not unlike the “Titans of old,” who were always invincible as long as both feet were planted firmly on good ground. To Babcock, hunting and fishing were true sports (unlike football or baseball, which are games) because they took place on good ground (in nature). And when in nature, one is forced to be alert, to be aware of the totality of one’s surroundings, not just of a playing field.

Babcock believed outdoor life, mixed with good friends and a little bourbon, did more to calm a man’s nerves than medicines or therapy. He always thought a fishing boat superior to any psychiatrist’s couch—and cheaper, too. To him human contact with nature was essential to good health and good sense. Nature also brought out the truth in people. It stripped away social pretenses and forced people to be self-reliant and self-reflective.

When at home in Columbia, Babcock channeled his love of the outdoors into his garden. He was an avid vegetable gardener, who again praised South Carolina for its mild climate, which allowed for year-round growth. Alice was an equally dedicated gardener, and became known throughout Columbia for her camellias. She would wear a fresh one on her blouse every day during the season. Today, several of her most prized specimens have been relocated from the old Babcock home to the Babcock Memorial Garden at the University of South Carolina.

Toward the end of his life Babcock saw South Carolina change. It went from an agrarian society to one enthralled by commercial growth. These changes brought unprecedented wealth and opportunity but also carried a heavy price, especially on the land and its people. Babcock loathed industrial agriculture in particular, as it transformed the entire landscape, making it monotonous and characterless. Industrial farming may have increased productivity, but it greatly reduced wildlife populations and forced people to head for the cities and towns. Gone were the split-rail fences, cut and built by hand, places where brambles and briars grew and where quail thrived.

Babcock did witness the building of South Carolina’s massive dams and reservoirs and thought them good for fishing. But he would have lamented the concentration of industry and development around these projects. This has made South Carolina’s waters some of the dirtiest in the country, rendering many of its fish toxic and inedible.

One of the most troubling developments, and one Babcock did not witness, is the dramatic decline of the South Carolina bobwhite quail population, which wildlife biologists estimate has decreased over 90 percent in the last 50 years. The spread of industrial agriculture, roads, housing developments, not to mention feral cats, wild pigs, and fire ants, has made life almost impossible for the quail, which (Babcock already knew) have no friends in nature.

And today Havilah Babcock would have no friends in the American university. The leftist takeover of literature departments would have been beyond his comprehension. And there would be absolutely no tolerance (or tenure) in these departments for a man like Babcock, who actually believed teaching was important, as was writing about things that interested the average educated person.

If he were alive today, Babcock would certainly have been troubled by the destruction of nature and culture in the South. But he would not have been discouraged. In fact he may even have anticipated it, as he always remained skeptical of ideas like “progress” and “growth.” In good Southern fashion he would have addressed these problems head on and, with characteristic wit and humor, properly exposed the foibles of those in power who promote them.

He would also have been happy to know that there are still many in his beloved South and throughout America who continue to live the life he cherished and will fight to protect it. Those who are committed to the outdoor life, and need some encouragement or reassurance as to its importance, need to go off and read a little vintage Babcock. And for those who have never heard of the man, it is high time to get acquainted.

Leave a Reply