It seems to me that in the present phase of European history the essential issue is no longer between Catholicism, on one side, and Protestantism, on the other, but between Christianity and Chaos. . . .

Today we can see it on all sides as the active negation of all that western culture has stood for. Civilization—and by this I do not mean talking cinemas and tinned food, nor even surgery and hygienic houses, but the whole moral and artistic organization of Europe—has not in itself the power of survival. It came into being through Christianity, and without it has no significance or power to command allegiance. The loss of faith in Christianity and the consequential lack of confidence in moral and social standards have become embodied in the ideal of a materialistic, mechanized state. . . . It is no longer possible . . . to accept the benefits of civilization and at the same time deny the supernatural basis upon which it rests.

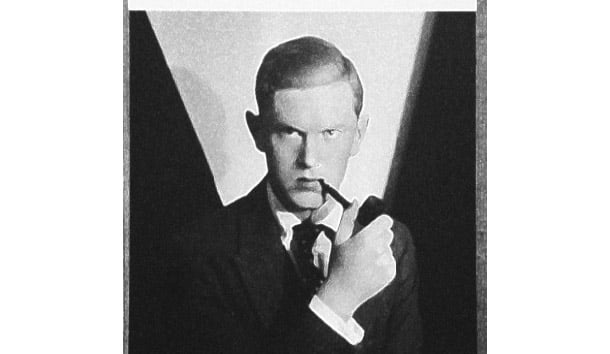

These fighting words, written by the novelist Evelyn Waugh in an article entitled “Converted to Rome: Why It Has Happened to Me,” were published in October 1930 in Britain’s Daily Express. Waugh’s full-page banner-headlined article followed two leading articles in the Express discussing the significance of his recent reception into the Catholic Church. On the day after the publication of Waugh’s article, E. Rosslyn Mitchell, a Protestant MP, wrote a reply, and, on the following day, Father Woodlock, a Jesuit, added “Is Britain Turning to Rome?” Three days later an entire page was given over to the ensuing letters.

Seldom had a religious conversion caused such controversy. Back in 1845, John Henry Newman’s conversion had rocked the establishment, as had the conversion in 1903 of Robert Hugh Benson, son of the archbishop of Canterbury, and the conversion in 1917 of Ronald Knox, son of the bishop of Manchester. Yet the consternation over Waugh’s conversion was different. Whereas these earlier controversial conversions had been connected to the defection of clergymen from one church to another, Waugh was regarded as a typical hedonistic modern youth who was presumed to have had an iconoclastic disdain for all religion. As such, his conversion was greeted with utter astonishment by the media and the literary establishment. On the morning after his reception into the Catholic Church the lead article in the Daily Express expressed bemused bewilderment that an author notorious for his “almost passionate adherence to the ultra-modern” could have become a Catholic.

Waugh’s Christian faith found expression in the novels published in the years following his conversion, especially in A Handful of Dust, which took its title from a line in The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot, whose own conversion to Anglo-Catholicism in 1928 had baffled the literati and the secular media. It is, however, Brideshead Revisited, which Waugh considered his magnum opus, that most successfully embodies the tension between Waugh’s ultramontane faith and the ultramodern world in which it found itself.

Published in 1945, Brideshead Revisited traces the interaction between Charles Ryder, its ostensibly agnostic narrator, and a family of aristocratic Catholics. In the Preface to the second edition, Waugh wrote that its theme was “the operation of divine grace on a group of diverse but closely connected characters.” This authorial exposition of the theme is key, unlocking the deepest levels of meaning in the work. The operation of divine grace means that there is a hidden hand at work, a supernatural presence acting on the characters. It’s as though the novel’s chief protagonist is God Himself, Whose omnipotent and omniscient presence guides the narrative. From a Christian perspective, this is nothing less than realism, in the sense that it reflects reality. It is, however, very difficult for a novelist to suggest this presence without descending to the level of didacticism and preachiness. It is a mark of Waugh’s brilliance that he succeeds with a theme that he himself described as “perhaps presumptuously large.”

Although the author’s epigraphic note—“I am not I: thou art not he or she: they are not they”—signifies the author’s desire to distance himself and his readers from any of the characters, it is evident that there is much of Waugh’s own preconversion self in the characterization of Charles Ryder, the agnostic narrator through whom we see the story unfold. And yet, with a stroke of subtle brilliance, Waugh subverts the agnosticism of the narrative voice through having it spoken by the older Ryder, recalling the events of his life from a mature middle age, at which point, as we discover in the Epilogue, he has himself embraced the Faith. Thus, the narrator expresses the religious doubts of his youth from the perspective of one who now doubts those doubts. In this sense, it is hard to see Ryder without seeing a shadow of Waugh, musing on his own loss of faith as a youth and his years as a hedonistic agnostic at Oxford. Ryder’s account of the disastrous effects of theological modernism on his own faith as a schoolboy reflects Waugh’s experience at Lancing College. Similarly, Ryder’s account of undergraduate decadence and debauchery reflects Waugh’s own riotous hedonism at Oxford.

The characters who breathe life into the novel are drawn with Dickensian dexterity and, on occasion, with Dickensian grotesqueness, suggestive of caricature, as in the case of the effete mannerisms of Anthony Blanche, the sordid creepiness of Mr. Samgrass, and the sadistic humor of Charles’s father, played to hilarious perfection by Sir John Gielgud in the British television adaptation of the 1980’s. As for the Catholic aristocratic family with whom Ryder interacts, they are some of the most memorable characters in modern fiction: Lord Marchmain, who deserts his wife and family and takes up with a concubine in Venice, is “conscious of a Byronic aura, which he considered to be in bad taste and was at pains to suppress”; Lady Marchmain, the deserted wife and mother, is pious but unable to win the affection of her children; Lord Brideshead, the eldest of the children and heir to the estate, is Jesuit-educated, deeply pious, but socially inept; Sebastian, Eton-educated and therefore ill equipped to grasp the rational underpinnings of faith, is self-consciously self-centered and lacks the desire or ability to grow up and grasp the responsibilities of adulthood; Julia, the older of the two daughters, is as self-centered as her brother, though less consciously, and shares his resentment of the way in which Catholicism is an obstacle to self-gratification; and Cordelia, the youngest of the family, is pious and precocious in equal measure, reminding us of her famous Shakespearean namesake.

The plot flows in two directions. In the first half of the novel, Sebastian and Julia stray further and further from their mother’s reach and further from the Faith with which they associate her. Sebastian descends into alcoholism and social dereliction, living a life of increased squalor in North Africa, while Julia makes a reckless and ultimately disastrous marriage to a cynical and ambitious politician and later begins an adulterous relationship with Ryder. We are told of the suffering that her children’s apostasy is causing Lady Marchmain, after Julia had “shut her mind against her religion.” She bore this and her new grief for Sebastian and her old grief for her husband and the deadly sickness in her body, and took all these sorrows with her daily to church.

It is after Lady Marchmain’s death that the tide begins to turn, or, to employ the metaphor that Waugh borrows from G.K. Chesterton, that there is the “twitch upon the thread,” which begins to tug the prodigals back. This metaphor for grace is mentioned by Cordelia as she contemplates the way in which her father had left both his wife and the Faith to which he had converted upon marrying her:

Anyhow, the family haven’t been very constant, have they? There’s him gone and Sebastian gone and Julia gone. But God won’t let them go for long, you know. I wonder if you remember the story mummy read us the evening Sebastian first got drunk—I mean the bad evening. “Father Brown” said something like “I caught him” (the thief) “with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world and still bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.”

From a worldly perspective, it is easy to find in Lady Marchmain a convenient scapegoat whose relentless adherence to the Faith has alienated her husband and children (or two of them at least) from herself and her religion. This is indeed the way that the novel is often read and taught in our meretricious age, which explains why the director of the recent and lamentably bad Hollywood adaptation of the novel proclaimed that, in his version, God was the enemy.

If, however, we take Waugh at his word and expect to find the operation of divine grace at work in the story, we need to seek the supernatural dimension. Lady Marchmain’s influence on her husband and children does not cease upon her death. Apart from the power that the memory of her evokes, there is the very real power of her continued prayers. Her ghost haunts her family, in the benign sense that she intercedes for them. Furthermore, it seems that her intercessory prayers are answered in dramatic fashion as Lord Marchmain, Julia, and Sebastian return to the fold.

And yet in each case, the conversion of heart comes with a great deal of suffering. “No one is ever holy without suffering,” says Cordelia, and it’s no surprise that the other powerful metaphor for grace that Waugh employs as the novel reaches its climax is that of an avalanche that destroys everything in its path:

And another image came to me, of an arctic hut and a trapper alone with his furs and oil lamp and log fire; everything dry and ship-shape and warm inside, and outside the last blizzard of winter raging and the snow piling up against the door. Quite silently a great weight forming against the timber; the bolt straining in its socket; minute by minute in the darkness outside the white heap sealing the door, until quite when the wind dropped and the sun came out on the ice slopes and the thaw set in a block would move, slide, and tumble, high above, gather weight, till the whole hillside seemed to be falling, and the little lighted place would open and splinter and disappear, rolling with the avalanche into the ravine.

The trapper is Charles Ryder, whose little world of comfort, planned with a future marriage to Julia in mind, is about to be swept away. Thus, as Julia decides that her dying father should see a priest, Charles has “the sense that the fate of more souls than one was at issue; that the snow was beginning to shift on the high slopes.” A little later, his worst fears are realized as Julia breaks off their engagement:

I can’t marry you, Charles; I can’t be with you ever again. . . . I’ve always been bad. Probably I shall be bad again, punished again. But the worse I am, the more I need God. I can’t shut myself out from his mercy. That is what it would mean; starting a life with you, without him.

The final words of the final chapter reprise the metaphor: “The avalanche was down, the hillside swept bare behind it; the last echoes died on the white slopes; the new mound glittered and lay still in the silent valley.” It ends, therefore, with Ryder’s life in ruins, swept away in the avalanche of grace that had brought Julia and her father back to the Faith. And yet, like every good Christian story, there is life after death, or, perhaps we should say, there is a resurrection.

Earlier in the novel, Charles had turned his back on Brideshead, the ancestral home of the Flyte family, the name of which is symbolic of the Church herself, the Bride of Christ whose head is Christ the Bridegroom.

But as I drove away and turned back in the car to take what promised to be my last view of the house, I felt that I was leaving part of myself behind, and that wherever I went afterwards I should feel the lack of it, and search for it hopelessly, as ghosts are said to do, frequenting the spots where they buried material treasures without which they cannot pay their way to the nether world. . . .

“I have left behind illusion,” I said to myself. “Henceforth I live in a world of three dimensions—with the aid of my five senses.”

I have since learned that there is no such world.

Here we see the subversive voice of the older Charles rebuking his younger self for his naive atheism. And it is this older Charles whom we meet in the Epilogue. Returning to Brideshead several years after the cataclysmic death of all his hopes, he kneels and prays before the tabernacle in the chapel. Like Julia, who is now symbolically in the Holy Land with Lord Brideshead and Cordelia, he has embraced the ancient Faith. At last, Charles can speak with the same voice as Waugh, who wrote of his own conversion that it was

like stepping across the chimney piece out of a Looking-Glass world, where everything is an absurd caricature, into the real world God made; and then begins the delicious process of exploring it limitlessly.

It is no wonder that we are told at the novel’s conclusion that Charles was “looking unusually cheerful today.”

Leave a Reply