It is said that whatever theme a poet chooses to deal with—the insignificance of a mouse or Prometheus’ heroic deed—what really matters is the ways in which a certain reality, certain feelings, and certain events are transposed into a poetic image. There are few objections to this opinion—it is supported by many works of art and by a sense of a general desecration of the world and the debasement of everything sublime. The greatest accomplishments of our time are unfailingly programmed in laboratories, while our heroes are mass-produced in advertising bureaus. Myths are no longer innocent stories about miracles, nor are heroes any longer mortals with divine gifts. The awareness of human infirmity and the lost hope that life can be made more sacred generates a widespread anxiety and fear syndrome. This has its effect in spiritual spheres as well. A mouse in its hole acquires an ever-growing symbolic importance and becomes a paradigm for the social and existential status of man.

The relation between reality and its artistic image is indeed the most complex problem of the whole theory of art. If art is not a reproduction, a mere reflection of reality, neither is it something completely independent. The argument about mimesis, which began in antiquity, is still unresolved.

Aristotle advised Protogenes, the painter who was making a portrait of his mother, to take the heroic deeds of Alexander the Great for his subject—deeds the whole world was talking about then, and which it was easily predictable the world to come would also be interested in. In Aristotle’s view, not all themes were equally valuable, and the artist had to choose those which would attract attention even in a remote future. Protogenes would not take his advice; he thought, as many among us still do, that themes and subjects cannot be graded according to the quantity of information they contain about a certain time.

Did the ancient painter make a mistake? If nothing else, had he listened, the portrait of Alexander the Great in our history textbooks might bear his signature; perhaps at least one of his works would have survived—although they were said to be so beautiful that Demetrius declined to storm a certain city, for fear that a Protogenes painting might be damaged in the attack. However, there are more serious reasons not to disregard Aristotle’s advice. If art is a testimony and a specific mirror of history—an assertion many today agree with—then we should not forget that Alexander’s accomplishments were the crucial determinants of his time and that they offered to the artist more possibilities to “capture” the Helenic spirit and to express himself as a creator and a witness than possibly any other contemporary subject.

We can only conclude that art has to deal with the important, with that which is a sign of recognition of a certain time, and which essentially determines our life. That crucial something that art speaks of is influenced, among other things, by the theme art chooses to deal with. When literature is in question, what is understood by the theme includes not only the subject but also that basic spiritual center which unifies and generates all meaning and which shapes the reader’s intuitive and rational understanding of a literary work. The theme influences the width and the depth of an artistic message and, by its general social, ethical, or philosophical meanings, deepens the artistic value of a work of art. It is on the theme, therefore, that the verisimilitude and truthfulness of the artistic picture of history largely depend. Hence, so-called taboo themes must not exist—artistic freedom must be fully guaranteed.

In societies where that is not so, literature and art in general have a slightly different function, and artists are confronted with a multitude of problems not necessarily of an artistic nature. Any critical reference to a taboo theme provokes an unpleasant reaction. This is easy to understand. But the greatest challenge, still, is the one concerning the nature of art. An author’s critical approach, implicit or explicit, also contains a more distinct artistic message, which, by its nature, lends itself to association with this or that idea. Therefore, from a sermon to the end of art, the road is neither long nor tortuous.

Though social engagement in literature has valid humanitarian and moral excuses, the doubt that such creativity is not fully integral is well-founded. The assertion, on the other hand, that an artist does not want to say anything, that he does not appeal for anything, and that the purpose of art lies only in its enjoyment is equally untenable.

Contemporary literature tries to overcome this theoretical discordance. Avoiding the sensitive question of engagement, it refrains from simple messages and assumes the role of a witness and accomplice. Its testimony endeavors to serve its highest principle—the truth.

Artistic truth differs from the historic; it is broader and multilayered, closer to the original Greek concept of “aletheia,” which denotes that which is not a mistake or a lie, as well as the habit of speaking truthfully, that is, sincerely, openly, particularly, and publicly. While historic truth quite often depends on the point of view and can be limited by ideological, religious, or moral barriers, artistic truth may be referred to as “righteousness.” This higher “righteousness” is very often established by deviation from historic truth. Let us remember, for example, the character of Napoleon in War and Peace; Tolstoy’s depiction is artistically justified and “righteous,” though it is not historic. True literature does not compete with history, nor does it reproduce the exact image of reality, but its illusion. Even literary chronicles based on historical facts, such as the great novels of Ivo Andric, are apocryphal flashes of history. Literature, respecting history, writes a story of its own time.

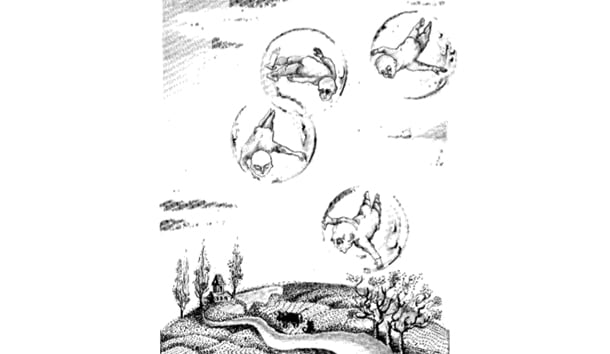

To make this story more convincing, writers use different techniques and different mirrors. The flat mirror, for example, reflects an object exactly but does not see far; it cannot bring closer what is distant, nor can it peek behind a hill; it cannot inflame a piece of paper nor cause a conflagration, as its myth-shaping brothers, convex, concave, or conic mirrors, can. They “revise” the image of an object according to their kind and capacity, without making it unrecognizable—what looms large they diminish; the small they expand—the distant and unseen they bring near; regular features they twist into masks; monsters they transfigure into graceful imps. These odd mirrors are the favorite instruments of modern literature. In a similar way, accord ing to its laws, literature transforms the picture of historical events, uncovering their less visible or less known characteristics.

If all this is not a matter of controversy, let us ask how our time is reflected in contemporary poetry. The answer is not easy to give; there are so many poets, poetics, and traditions. Every master has his own master script. But, putting all differences aside, they all have something in common—the creation of verses and the pursuit of the poetic act itself. For a century now, poetry has been looking obsessively into its own image; it has been dealing with its own language and with its own artistic temptations; it has been taking the nature of poetry and the lot of the author as its principal problem. Caught in its own hermetic circle, it views the world from the inside, as something external, foreign, and threatening. The world is no longer a poet’s home but his quarantine.

Poetry became lost in the endless lyrical space which Mallarme opened to it. More and more, poets resemble alchemists or conspirators who communicate in an arcane tongue. Poetic teachings attract only the initiated, the specialists and fellow sufferers who spend their days in libraries and institutes or gather only for symposiums and congresses. The discreet but firm bond between poets and readers is almost cut off. Poetry’s esoteric formulas and “healing” spells do not disturb the world; they put it to sleep instead. This lost communication cannot be explained only by the unintelligibility of poetic language. The misunderstanding is much deeper and relates, most of all, to what modern poetry is saying. Or, to put it better, to what it is not saying.

It has been assumed that the poetry speaks of something exceptional, something of crucial importance to every man. But for that to be true, poetic speech has to correspond with history and to discuss, in its own poetic way, the essential questions of its time. Modern poetry has been neglecting this task for too long and has been wandering in a circle instead—like the uroboros passionately biting its own tail.

In today’s world there are famous poets still—embodiments of the watchful conscience of contemporary society; but if the nonliterary echo engendered by their humanitarian, libertarian, or propaganda actions were taken away, their number would be greatly reduced.

It is, of course, difficult to prove such an assertion; poetry never speaks with a single voice. A multitude of works of art strives to convince us of the opposite. Questioning itself, poetry at the same time poses questions about the destiny of the world.

One has also to keep in mind that “the hand of a writer is neither completely in his own power nor in the power of some blind passion; another Hand supports it and leads it across the paper so that, consciously or unconsciously, his work, merely by the way words in a sentence are strung together, serves as a testimony of time and space.” According to this statement by Czeslaw Milosz, the text is a kind of a cardiogram; the poet is inexorably committed to a role of the witness of history. Literature, therefore, cannot be only a mere game of words. Such a conviction, beyond any doubt, reinforces the poetry of Milosz himself But, were it only reduced to the hand’s trace, to rhythm, to syntax, to contextual layer of meaning, and to the role of the “unconscious,” such poetic testimony certainly would not generate the excitement that Milosz’s poetry offers. And this is yet another proof that a poet has to deal with crucial moments in history, with what determines the “pulse” of a certain age. The value of his testimony and the value of the poetic work itself depend on that.

Therefore it seems necessary to think twice about Aristotle’s advice. The consequence should not be, of course, a catalog of prescribed themes in which the building of a White Sea canal or the flight to the moon would be recommended as the Alexandrian feats of our age.

The poet is only partly a member of society; his speech is personal, and no one can prompt him as to what he should speak about. But his monologue is meant for others as well and, lacking response, becomes absurd. The reader must respond if art is to have any meaning at all. What today’s reader should be told, I do not know; but it is certain that poetry should say much more than, it does. Otherwise, the reader will become completely deaf to it.

You might not be aware of how the “Bop” was born. When a policeman hit a black on the head, his nightstick sang, “Be! Bop! Be-bop! Bop!” At least this is the explanation offered by Langston Hughes. Let it be, then, my own message to lovers and writers of verse: The stroke of this age upon our heads has to find its onomatopoeia in contemporary poetry.

Leave a Reply