As things continue to assume a pear shape in almost every sphere of American life, particularly in our cultural institutions, we would do well to remain vigilant about falling into the abyss of nostalgia. Even so, this admonition doesn’t, and probably shouldn’t, stop some from yearning for the days when writers had talent and guts. Tom Wolfe (1930-2018) was one of those few talented and courageous American writers. A new documentary, Radical Wolfe, directed by Richard Dewey, offers a portrait of Wolfe as a true radical—a one of a kind, larger-than-life cultural figure.

The documentary is based on Michael Lewis’s 2015 Vanity Fair article, “How Tom Wolfe Became … Tom Wolfe,” and Lewis features prominently in the film’s interviews. Others interviewed include Gay Talese, Lynn Nesbit, Christopher Buckley, Niall Ferguson, Tom Junod, and Alexandra Wolfe (Wolfe’s daughter). It is as much about Wolfe himself as about America’s turbulent time in the 1960s and changes that came in the following decade.

Wolfe is known as the founder of the New Journalism—a technique of combining journalistic reporting with a writer’s artistic, subjective viewpoint. Hating the objective voice that is supposed to be the cornerstone of journalism, Wolfe decided to shake things up a bit. He inserted himself into the events and began seeing and describing life in America through the lens of his unique personality. (For my part, I think Wolfe was the New Journalism, and it is an unrepeatable reality. Imitators remain just that.)

At the beginning of his career, Wolfe wrote straightforward articles, but things changed radically for him with his 1963 Esquire essay, “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmm).” Sixty years later, and this title is still “out there”—as radical as you it gets.

Writing about the world of custom cars, Wolfe tapped into the subject of not only cars but America herself. What followed were essays upon essays, books upon books, showing every aspect of American life—be it good or bad—but without ever demonstrating one shred of hatred for it. Wolfe retained his Virginia gentlemanliness, although on paper he could be brutal. When another radical, William F. Buckley, Jr. asked Wolfe to comment on his alleged lack of compassion, Wolfe responded that it is not his job as a writer to be compassionate but to present the truth, and that “truth is revolutionary” by its very nature.

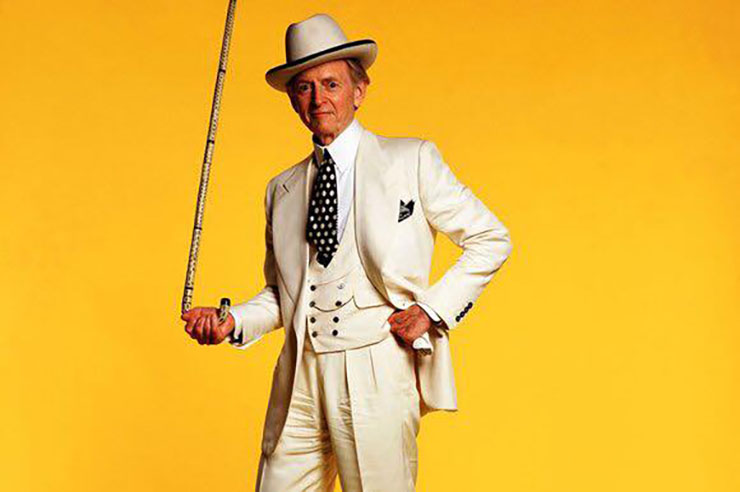

Wolfe never tried to blend in, as wearing a white suit and looking a bit like a Southern dandy made him stand out. Once, he managed to secure an invitation to a Leonard Bernstein party that hosted the Black Panthers. What followed was an essay called “Radical Chic,” which became a phrase so often repeated American culture that people frequently forget the origins. Needless to say, the Bernstein family did not appreciate this at all (and according to the documentary, they’re still hurt by it). But how does one write “compassionately” about the absurdity of New York socialites mingling with a group that seeks justice through violence? It’s safe to say the raison d’être of Black Panthers doesn’t fit well with Lenny’s hors d’oeuvres.

One of Wolfe’s gifts was to bring different kinds of Americans together. Many commentators in Radical Wolfe recognized this, especially Michael Lewis. In fact, it’s Lewis’s fond memories of his friendship with Wolfe as well as its exploration of Wolfe’s books that saves the documentary from its insistence on remaining safe and inoffensive. Lewis is wonderfully enthusiastic about Wolfe. Without a hint of cynicism, Lewis opens up about why Wolfe means so much to him and laments the fact that no one today has a similar kind of guts to say what he thinks.

If only the makers of this documentary had heeded Lewis. For this seems to be the problem with the documentary: There is a smell of ideological equivocation. On one hand, we hear from people like Christopher Buckley and Peter Thiel, but on the other, we hear from a former Black Panther who expresses his disgust with Wolfe’s alleged wrongdoing in writing “Radical Chic.” Here’s a kicker that Tom Wolfe himself would find hilarious: this same former Black Panther is now a professor at Columbia University. Radical chic has never left the public square, and Wolfe is vindicated in his opinion.

But Wolfe wasn’t really a man of the political left or right. His crusade, if he even had one, was about freedom of expression and the fearless discovery of truth. This means that everything is on the table, and no one was “marked safe” Wolfe’s mighty pen.

Wolfe was not afraid. Whether it was part of a persona he created (along with his white suit) or if he was authentically just being himself, he did not hold back. Today, censorship has become such a stifling part of culture that it is difficult to escape its clutches. Much as in the former Soviet Union, many Americans engage in self-censoring for fear of being “canceled”—whatever that even means.

We are instructed to use euphemisms, to make one group of people feel better, to not boast about excellence, to decrease ourselves so that mediocrity has a chance at winning. Maybe this was the case even during Wolfe’s time, but being a free writer today is certainly a tough road to navigate.

Dewey’s documentary is not critical of Wolfe, nor does it diminish his talent. But it lacks the thrust that Wolfe himself had. It is sad that the very thing that Wolfe presented in “Radical Chic” is actually on display in Radical Wolfe. And so, it becomes an occasion for sadness (something that Michael Lewis expresses in the documentary) and “remembrance of things past.”

Truth is revolutionary, and it requires the courage to be. Wolfe certainly had plenty of that, and his chronicles of America will continue to be rediscovered. As for new, better, and courageous literary and cultural voices in America, it remains to be seen.

Leave a Reply