“I once voted at a presidential election. There being no real issue at stake, I cast my vote for Jefferson Davis of Mississippi. I knew Jeff was dead, but I voted on Artemus Ward’s principle that if we can’t have a live man who amounts to anything, by all means let’s have a first-class corpse.”

—Albert Jay Nock, A Journal of These Days

One of the hazards of Washington life is the risk of running into people whose politics is their religion. You see them everywhere at receptions, eyes blazing with unhallowed fire, proselytizing for a cause whose victory is always within sight.

The right-wing political fanatic wages war on the pleasures of life. If only pornographic magazines, mood-altering drugs (except vermouth), and premarital sex could be banned, then Americans would stand tall, keep their hair short, and vote a straight Republican ticket until they die. The left-wing political fanatic has her mind on one Important Subject, which is the core of her existence. Anyone who does not spend every waking moment worrying about the nuclear freeze or South Africa is simply not a caring person.

Whenever I cross paths with one of these people, I wish I had a copy of Albert Jay Nock’s Memoirs of a Superfluous Man. I would fortify myself with Nock’s advice. “One of the most offensive things about the society in which I later found myself was a monstrous itch for changing people,” he wrote. “It seemed to me a society made up of congenital missionaries, bent on reforming and standardizing people according to a pattern of their own devising . . . the moment one wishes to change anybody, one becomes like the socialists, vegetarians, prohibitionists; and this is, as Rabelais says, ‘a terrible thing to think upon.'”

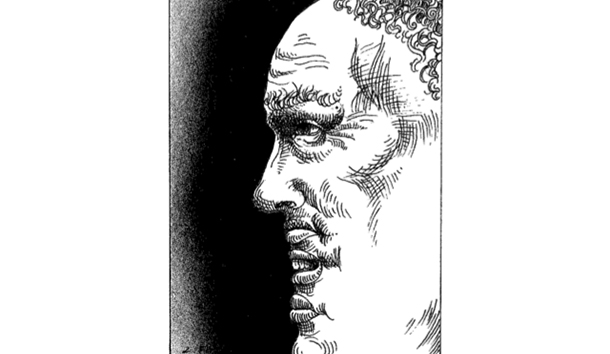

Few people read Nock these days. That is a shame. Nock was one of the great curmudgeons of American journalism, a first-class grouch whose opinions seasoned dozens of issues of Harper’s, The Atlantic, The American Mercury, and most of the other major journals of the 20’s and 30’s. “Albert Jay Nock belongs to the great American tradition of the judicious eccentric,” says Jacques Barzun, “a genuine political mind, a true scholar, an intellectual hedonist whose classic prose is graced with insidious wit.”

Nock spent the first four decades of his life searching for a vocation. Born in Brooklyn in 1870, he was graduated from St. Stephen’s College, later “reorganized off the face of the earth” to become Bard College. Nock drifted through the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, first as a semiprofessional baseball player, then as an Episcopalian minister. In 1908, he went through a messy divorce which led him to abandon wife, children, and church for a year of recovery in Brussels. When he returned. Nock began his second career as a writer.

For the first 10 years of his career, he was seen as a liberal. He spent five years as an editor at The American Magazine, a muckraking monthly featuring the work of Lincoln Steffens and Ida Tarbell. Steffens remembered Nock fondly in his memoirs as “that finished scholar [who] put in mastered English for us editorials which expressed with his grave smile and chuckling tolerance ‘our’ interpretations of things human.”

In 1914, Nock met Francis Neilson, a prominent politician in the British Liberal Party. Neilson had the manuscript of How Diplomats Make War, a study of the machinations of the British Foreign Office. Nock found a publisher and provided an introduction, stating that Neilson’s work would “shift our sympathies squarely away from the whole filthy prairie-dog’s nest of traditional diplomacy, wherever found.”

Neilson was to repay Nock’s favor many times over. In 1917, he married Helen Swift, heir to the meat-packing fortune. Mrs. Neilson paid for Nock’s salary at The Nation, where for two years he assisted Oswald Garrison Villard in attacking the Versailles Treaty and Allied intervention in the Russian civil war. Nock, however, was unhappy working for another editor. He wanted his own journal, and, thanks to Mrs. Neilson’s money, he was to get his wish.

Nock and Neilson edited The Freeman from 1920 until 1924. Modeled after the Spectator, it was planned as “a Radical paper,” in the tradition of Cobden and Bright, “opposed to all the nostrums of Socialism and bureaucratic paternalism.”

Most of the intellectuals prominent in the early 20’s wrote for The Freeman; its pages were filled with articles by Charles Beard, Hendrik Van Loon, Bertrand Russell, and H.L. Mencken. The literary pages, edited by Van Wyck Brooks, featured reviews by Conrad Aiken, John Dos Passos, and Carl Sandburg. Nock was the impresario of The Freeman, supervising production and writing dozens of articles, blasting the Harding administration for everything from high-tariff policies to punitive measures against a defeated Germany. Yet even as Nock frenetically produced diatribe after diatribe, the quietism which was to mark his philosophy was already beginning to emerge.

It was on August 11, 1920, that Nock first discussed the idea of the “superfluous man.” “Our universities boast that they are becoming helpmates of business,” Nock wrote. “The machinery of business speeds forward faster and faster, and, as it speeds, human nature becomes, beneath the surface, more and more recalcitrant. The most cynical, the most thick-skinned of people begin to ask themselves where they are going and for what purpose.”

Nock believed that “these bolshevists of the spirit . . . wanderers who can not find themselves, who can not fit in,” could not be redeemed by commercial America. It was only by examining the masterpieces of the past, the “great companions who have given to mankind its literature and its religion,” that the American wanderer could find his spiritual roots and finally flourish. “Having access to the whole world of psychology, philosophy and history,” Nock concluded, “they are under the free moral obligation to see themselves in the common sunlight.”

It was that sunlight—eternally emanating from the classics of the past—that Nock was to turn to after The Freeman ceased publication in 1924. First came Jefferson (1926), which celebrated the part-time inventor and genteel anarchist while ignoring the President who purchased Louisiana. Then came other worthy books: The Theory of Education in the United States, A Journal of These Days, A Journey Into Rabelais’s France. It was with Our Enemy, the State (1936) that Nock secured his reputation.

It took some courage on Nock’s part to write a tract calling the State “the only professional criminal class” at the height of the New Deal. Franklin Roosevelt was, to Nock, the American Domitian, the man who destroyed the last vestige of independence by the states in his relentless quest to make Washington into a devouring imperial capital. The ordinary citizen, Nock believed, would sheepishly accept the New Deal; a “peculiar moral enervation existed in regard to the State,” Nock wrote, creating a silent majority that blithely ignored the judicial empire-building of John Marshall, the “monocratic military despotism” of Lincoln, the foreign imperialism of McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, and the domestic imperialism of Franklin Roosevelt. (In Nock’s eyes, only the protests against atrocities in the Spanish-American War of 1898 “marked the last major effort of an impotent and moribund democracy.”)

As Western civilization slowly sank beneath the weight of government expansion. Nock saw a way of escape. There were a few people, he believed, who would be willing to free themselves from the constricting bonds of ideology. These people Nock called “the Remnant,” people who “have an intellectual curiosity, sometimes touched with emotion, concerning the august order of nature; they are impressed by the contemplation of it, and like to know as much about it as they can.”

The goal of the Remnant, Nock explained in a 1936 essay, was to “proceed on our way, first with the more obscure and extremely difficult work of clearing and illuminating our own minds, and second, with what occasional help we may offer to others whose faith, like our own, is set more on the regenerative power than on the uncertain achievements of premature action. . . . Those who have this power are everywhere; everywhere they are not so much resisting as quietly eluding and disregarding all social pressure which tends to mechanize their processes of observation and thought.”

Nock was an elitist, but he denied he was a conservative. He refused to join anti-New Deal organizations and in a 1937 essay insisted on his independence from the nascent conservative movement. “When occasion required that I label myself with reference to particular social themes or doctrines, the same decent respect for accuracy led me to describe myself as an anarchist, an individualist, and a single-taxer.”

“I see I am now rated as a Tory,” he wrote Bernard Iddings Bell in 1933. “We have been called many bad names, but that takes the prize.”

Nock spent the waning years of the 30’s recapitulating his earlier themes. There were many essays, none major, as well as Henry George: An Essay, a curious tribute to the Victorian single-tax advocate. It was only when a publisher proposed his autobiography that Nock got out of his rut and tried something new. Nock had mulled over an autobiography in the past, but rejected the confessional or gossipy approach: “I have led a singularly uneventful life,” he wrote in the preface to the Memoirs, “largely solitary, have had little to do with the great of the earth, and no part whatever in their affairs or for that matter, in any other affairs.”

The Memoirs is the most reticent American autobiography since The Education of Henry Adams. Nock’s family is never mentioned: His friends only exist to provide philosophical nuggets. Even The Freeman is never cited by name. The Memoirs is, in Nock’s words, “the autobiography of a mind in relation to the society in which he found itself”

The Memoirs of a Superfluous Man is the story of an ordered mind in a disordered world, the story of a man who momentarily found Eden and spent the rest of his life trying to regain it.

Eden, for Nock, was at St. Stephen’s College, “situated on the blank countryside” of upstate New York. St. Stephen’s was paradise, because it taught the permanent things; case-hardened by more than 500 years of testing, St. Stephen’s curriculum—Greek, Latin, logic, classical philosophy—allowed Nock to see the world with “a feeling of intense longevity” granted by relentless analysis of the literature of Greece and Rome.

What undermined St. Stephen’s, in Nock’s eyes, was the dominance of the masses in everyday life. Nock thought America was a country in which everyone was equally free to be equally dull. The mass-man, in Nock’s eyes, lived for vicarious violence and invincible ignorance. “The ideals I have seen most seriously and purposefully inculcated (since 1914) are those of the psychopath on the one hand; and on the other, those of the homicidal maniac, the plug-ugly and the thug.” (One wonders what Nock would have thought of Sylvester Stallone.)

Nock saw two ideologies competing for the appetites of the masses. The more evil was worship of the State. The State’s only purpose, for Nock, was “continually absorbing through taxation more and more of the national wealth.” To do this, it dulled the masses by inflating threats posed by overseas menaces. “What best holds people together in pursuance of a common purpose is a spirit of concentrated hate and fear.”

The State, through government-run schools, strove to keep the citizens as ignorant as possible. Intelligence was more of a threat to the growth of the State than foreign foes; an intelligent mind knows that the State is not omnipotent and omniscient, and this knowledge is dangerous. “What was the best that the State could find to do with an actual Socrates and an actual Jesus when it had them? Merely to poison the one and crucify the other; for no reason but that they were too embarrassing to be allowed to live any longer.”

If the State thrived on dull citizens, capitalists thrived on greedy ones. Nock was a harsh foe of what he called “economism,” the belief that the only purpose in life was to acquire and distribute goods. An America where the prime virtue was to “scuffle for riches” was, for Nock, uncivilized, a country “without savour, without depth, uninteresting, and withal horrifying.”

For Nock, the robber baron was as much a mass-man as the poor people who were nominally his slaves. For a mass-man to worship an Andrew Carnegie or a Henry Ford was to worship a mirror; the rich were “mass-men, every mother’s son of them; unintelligent, ignorant, myopic, incapable of psychical development, but prodigiously sagacious and prehensile.”

Nock believed in an elite—the Remnant—but he did not feel that the elite in America should control the masses. Lusting for power was a specious reason to live. He believed in a philosophy of “egoistic hedonism,” of performing deeds not for the sake of improving others, but for the delight that derives from doing a deed.

Working for the benefit of “society,” in Nock’s opinion, was not possible. Society does not exist in anything more than “a concourse of very various individuals about which, as a whole, not many statements can be made.” An individual cannot “do good” towards an anonymous mass, because “good” is something that can only be transferred from individuals to other individuals. “Society” does not have any organs capable of appreciating worthy deeds.

If “society” remains impervious to individual acts, then a life devoted to political action is not fruitful. Rather than lobbying to change the State, the Remnant should adopt Candide’s motto—Il fait cultiver notre jardin.

“These few words sum up the whole social responsibility of man,” Nock concluded. The “garden” of the mind, nourished through judicious reading and conversations with stimulating friends—this was the only “garden” that counted. To let the mind lie fallow while “prescribing improvement for others . . . to organize something, to institutionalize this-or-that, to pass laws, multiply bureaucratic agencies, form pressure-groups, start revolutions, change forms of government,” was the gravest form of self-inflicted damage.

Nock is not entirely pervasive on this point. Good deeds may, in fact, be useful, provided they are given from individuals to other individuals. There is a difference between giving food to a starving neighbor and lobbying against cuts in the food-stamp budget, between helping refugees from Communism adjust to American life and campaigning for Star Wars. It is the difference between living for yourself and living for a cause.

Leave a Reply